Molecule on brain blood-vessel walls may contribute to aging-related forgetfulness

By Bruce Goldman

If old mice wore reading glasses, they'd constantly be forgetting where they left them.

Am I saying mice are people? Well, no, but there are similarities: Mice become forgetful in old age, just as some older humans do. And we're all hoping to live long enough to grow old, true? That's why a new study published in Nature Medicine strikes me as fascinating and momentous.

In this study, old mice suffered far fewer senior moments during a battery of memory tests when Stanford investigators directed by Stanford neuro-immunologist Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD, disabled a single molecule dotting the mice's cerebral blood vessels. For example, they (the mice, not the scientists) breezed through a maze with the panache characteristic of young adult mice.

From my news release about the study:

Since his lab first began reporting several years ago that unknown factors in old blood can accelerate cognitive decline and, conversely, that factors in young blood can rejuvenate old brains, Wyss-Coray... has sought to identify those factors. But he and his colleagues took a different tack in the new study.

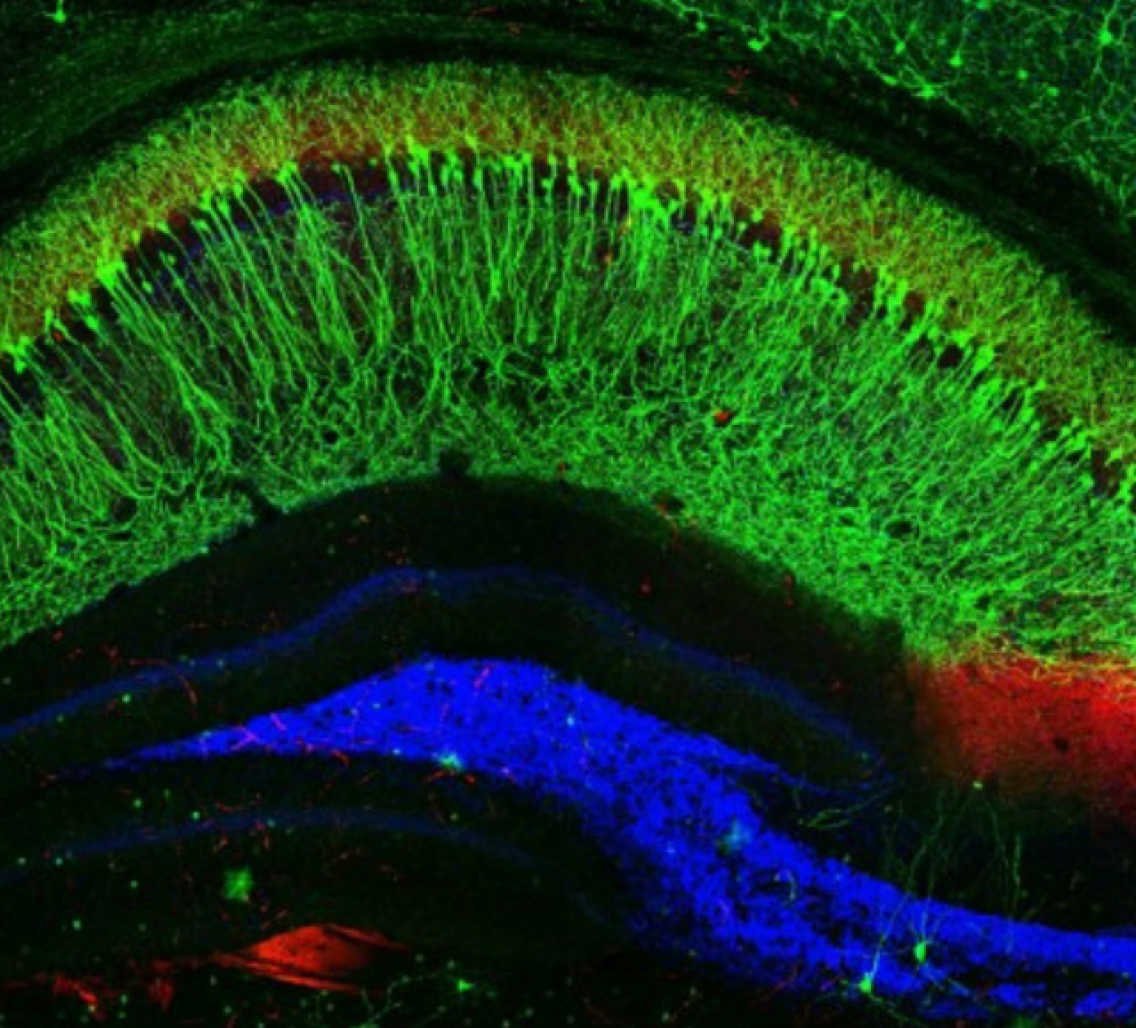

This time, instead of sifting through blood to find the culprits, they decided to check out the action at the so-called blood-brain barrier. The blood vessels perfusing our brains (and mice's) differ from those elsewhere in the body in one important respect: They're much more selective about what gets in and what comes out.

Wyss-Coray's team combed through a long list of molecular nuts and bolts composing both human and murine vasculatures to see if, and how, any of those components might facilitate old blood's nefarious capacity to cause the brain to rust out.

Sure enough, topping the list was a suspicious blood-vessel-wall-associated protein that, in both mice and humans, gets much more abundant on blood-vessel walls as individuals get older. From my release:

The protein, VCAM1, is well known to immunologists. It's a docking station for circulating cells of the immune system -- a first stop in a passport-punching process that under certain relatively rare conditions grants those immune cells permission to migrate across the brain's otherwise tightly closed border.

...

Blocking this molecule's capacity to do its main job -- it selectively latches onto immune cells circulating in the bloodstream -- not only improved old mice's cognitive performance but countered two physiological hallmarks of the aging brain: It restored to a more youthful level the ability of the old mice's brains to create new nerve cells, and it subdued the inflammatory mood of the brain's resident immune cells, called microglia.

Bottom line: A single protein protruding from blood-vessel walls in the brain seems to be the first digit in the combination lock the molecular malevolences in our blood have to pick in order to get inside our brains and mess them up so we don't learn as quickly or remember as well as we used to when we were younger.

The cognitive-test improvement in the old mice in this study was, in Wyss-Coray's words, the best he's ever seen in his experience. And he's tested a lot of mousey IQs.

The protein in question is situated right on blood-vessel walls, so it's accessible to drugs that no longer have to be able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier to turn off an offending brain mechanism. That's a big plus.

In fact, bulky drugs targeting this very molecule are already sitting on the shelves of pharmaceutical companies that were developing it as a multiple sclerosis therapy (because it would stop the aforementioned early step in the entry of immune cells into the brain), Wyss-Coray told me. But their candidate got aced out by another drug, marketed as Tysabri. Maybe now's a good time to pick it up and run with it.