Lianne Kolirin

A man paralyzed from the neck down for almost a decade has used his mind to compose whole sentences in real-time, according to a new study.

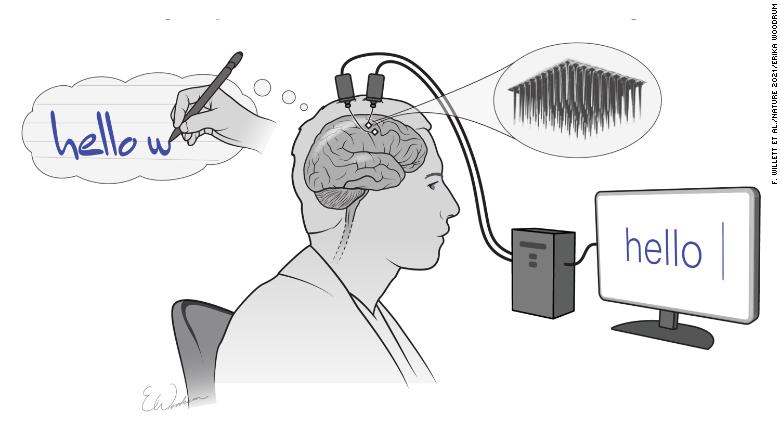

Scientists implanted two tiny sensors made up of hair-fine electrodes -- 4 x 4 millimeters -- into the left side of his brain to allow him to write his thoughts -- a skill called "mindwriting" by researchers. The man was 65 at the time of the study, which was conducted nine years after he suffered a spinal cord injury in 2007. He was asked to imagine holding a pen and paper and then try to write. The sensors placed in the outer layer of his brain detected the activity as he mentally visualized the movement. An algorithm then decoded the motion for each letter, translating it into text which appeared on a computer screen. The man -- known only as T5 -- was able to communicate by text at speeds rivaling those achieved by his able-bodied peers texting on a smartphone, the team of researchers from Stanford University in California said. Two tiny sensors relayed information from the brain area that controls the hands and arms to an algorithm, which translated it into letters that appeared on a screen.

Using the "brain-to-text" system, T5 typed 90 characters -- or 18 words -- per minute -- more than double the previous record for typing with such a "brain-computer interface," the team reported in the journal Nature Wednesday. An able-bodied person, on average, can type about 23 words per minute on a smartphone, researchers said.

The findings could spell new hope for millions around the world who have lost the use of their upper limbs or their ability to speak due to illness or injury, said Jaimie Henderson, professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, in a statement.

"The goal is to restore the ability to communicate by text," said Henderson.

When a person experiences paralysis, the brain's neural activity for actions like walking, grabbing a drink or speaking remain. The aim of research like this is to tap into this activity to help regain lost abilities.

Frank Willett, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) research specialist and neuroscientist who worked with Henderson, told CNN the team worked on the project for around two years, but the department has "a long history of developing brain-computer interfaces to help people with paralysis."

Henderson said the new development could be life changing for those who have suffered devastating injuries like brain stem stroke, which afflicted Jean-Dominique Bauby, the author of the book "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly."

"He was able to write this moving and beautiful book by selecting characters painstakingly, one at a time, using eye movement," Henderson said. "Imagine what he could have done with Frank's [Willett] handwriting interface."

Two tiny sensors relayed information from the brain area that controls the hands and arms to an algorithm, which translated it into letters that appeared on a screen.

Using the "brain-to-text" system, T5 typed 90 characters -- or 18 words -- per minute -- more than double the previous record for typing with such a "brain-computer interface," the team reported in the journal Nature Wednesday. An able-bodied person, on average, can type about 23 words per minute on a smartphone, researchers said.

The findings could spell new hope for millions around the world who have lost the use of their upper limbs or their ability to speak due to illness or injury, said Jaimie Henderson, professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, in a statement.

"The goal is to restore the ability to communicate by text," said Henderson.

When a person experiences paralysis, the brain's neural activity for actions like walking, grabbing a drink or speaking remain. The aim of research like this is to tap into this activity to help regain lost abilities.

Frank Willett, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) research specialist and neuroscientist who worked with Henderson, told CNN the team worked on the project for around two years, but the department has "a long history of developing brain-computer interfaces to help people with paralysis."

Henderson said the new development could be life changing for those who have suffered devastating injuries like brain stem stroke, which afflicted Jean-Dominique Bauby, the author of the book "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly."

"He was able to write this moving and beautiful book by selecting characters painstakingly, one at a time, using eye movement," Henderson said. "Imagine what he could have done with Frank's [Willett] handwriting interface."

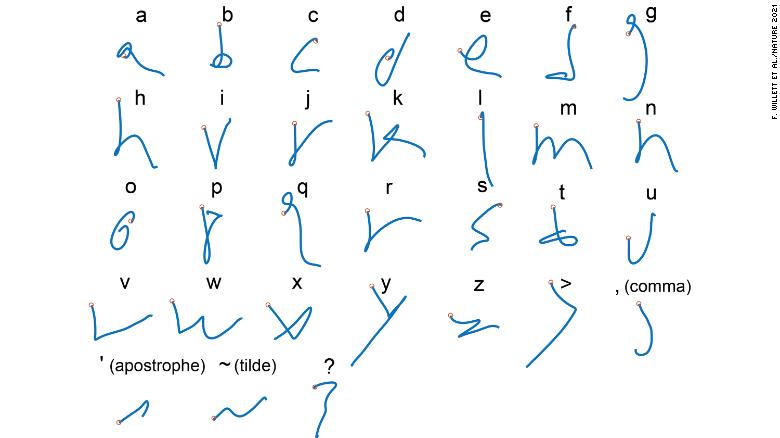

As the participant imagined writing a letter or symbol, sensors implanted in his brain picked up on patterns of electrical activity, which an algorithm interpreted to trace the path of his imaginary pen.

The revolutionary approach allowed the man to write twice as quickly as he could using a previous method developed by the researchers, which enabled letter selection with a thought-controlled computer cursor.

One of the "exciting aspects" of the study, according to Willett, was that T5 was still able to "write" clearly despite having suffered the spinal injury many years previously.

Willett said: "We still recorded highly structured and meaningful patterns of neural activity when he tried to handwrite."

The innovation could one day allow people with paralysis to rapidly type without using their hands, according to Krishna Shenoy, a HHMI investigator at Stanford who jointly supervised the work with Henderson.

Considerable work needs to be done before the technology is widely available, Willett told CNN -- though the hope is that "it will likely take at least years, but we hope not decades."

As the participant imagined writing a letter or symbol, sensors implanted in his brain picked up on patterns of electrical activity, which an algorithm interpreted to trace the path of his imaginary pen.

The revolutionary approach allowed the man to write twice as quickly as he could using a previous method developed by the researchers, which enabled letter selection with a thought-controlled computer cursor.

One of the "exciting aspects" of the study, according to Willett, was that T5 was still able to "write" clearly despite having suffered the spinal injury many years previously.

Willett said: "We still recorded highly structured and meaningful patterns of neural activity when he tried to handwrite."

The innovation could one day allow people with paralysis to rapidly type without using their hands, according to Krishna Shenoy, a HHMI investigator at Stanford who jointly supervised the work with Henderson.

Considerable work needs to be done before the technology is widely available, Willett told CNN -- though the hope is that "it will likely take at least years, but we hope not decades."