To study aging, researchers give killifish the CRISPR treatment

Claire Bedbrook and Ravi Nath came to Stanford for the fish.

The friends had bonded as Caltech graduate students over a shared curiosity about a fundamental biological mystery: Why do we age, and what controls our lifespans? So when they first learned about the short-lived African turquoise killifish, they knew it was the model organism for them.

Thanks to the work of Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute faculty member Anne Brunet and colleagues, the speckled, two-inch-long killifish has become a promising research model for studying aging — largely because it reaches its “golden years” within a matter of months.

“We thought, this is a cool, genetically tractable system that’s being pioneered at Stanford, and we want to go be a part of that,” said Nath, who is now a postdoctoral fellow supported by the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Wu Tsai Neuro.

Bedbrook and Nath are now working with Brunet and fellow Wu Tsai Neuro faculty affiliate Karl Deisseroth as part of a team spearheading an ambitious research effort — supported by a Catalyst award from the Knight Initiative — to use the tiny fish to understand the specific genetic and behavioral factors that control aging across the lifespan.

But first, the researchers had to clear a major hurdle. They had the tools that they needed to “knock out,” or switch off, killifish genes to test their functions, but no way to add, or “knock in,” new genes. This was a major limitation: Bedbrook had spent her PhD designing genes that could make mouse neurons responsive to light, and now she had no way to deploy such genes in her new model organism.

“We wanted to start working with the fish just like people do neuroscience research in mice,” said Bedbrook, whose research is supported by an Interdisciplinary Scholar Award from Wu Tsai Neuro. “And right away, we ran into the problem that we don’t have any way of actually introducing these genes.”

This barrier has now been overcome. On May 16, 2023, Bedbrook, Nath and colleagues reported in the journal eLife that they had successfully inserted a variety of genes into the killifish genome—and even created self-perpetuating lines of mutant animals.

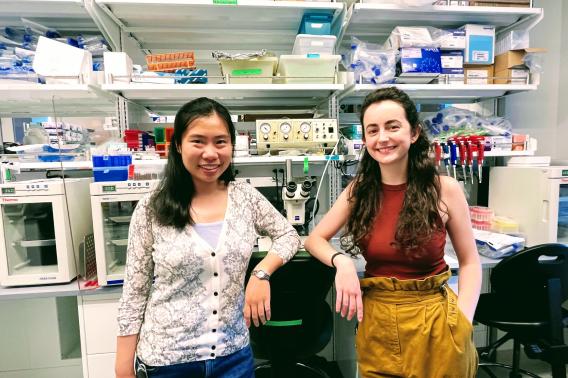

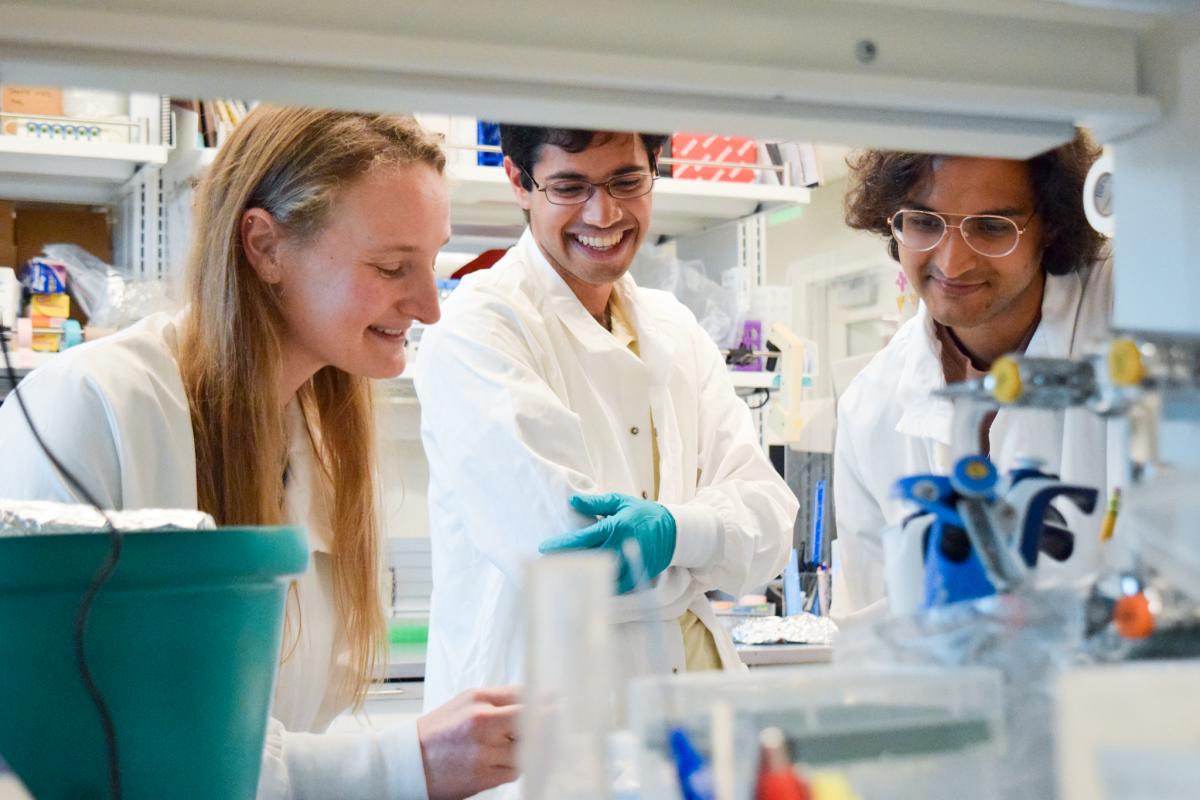

Study authors Claire Bedbrook, Rahul Nagvekar, and Ravi Nath work together in the Brunet Lab at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Image credit: Nicholas Weiler.

Finding the right recipe

As recently as a decade ago, making genetically engineered animals was a laborious, expensive process. But ever since the discovery of CRISPR, in 2012, inserting mutated genes into lab animals has become the labor of an afternoon—at least, that is, if you’re using a standard lab animal. While CRISPR “molecular scissors”can cut through DNA to make space for new genetic elements, other tools are needed to get those elements to stick in the right place, and different animals require different recipes.

Bedbrook, Nath and Brunet lab grad student Rahul Nagvekar hit on the right recipe fairly quickly. After a couple of months of experimentation, they hit on a remarkably effective technique, and more than 40 percent of fish ended up carrying the new genes after injection.

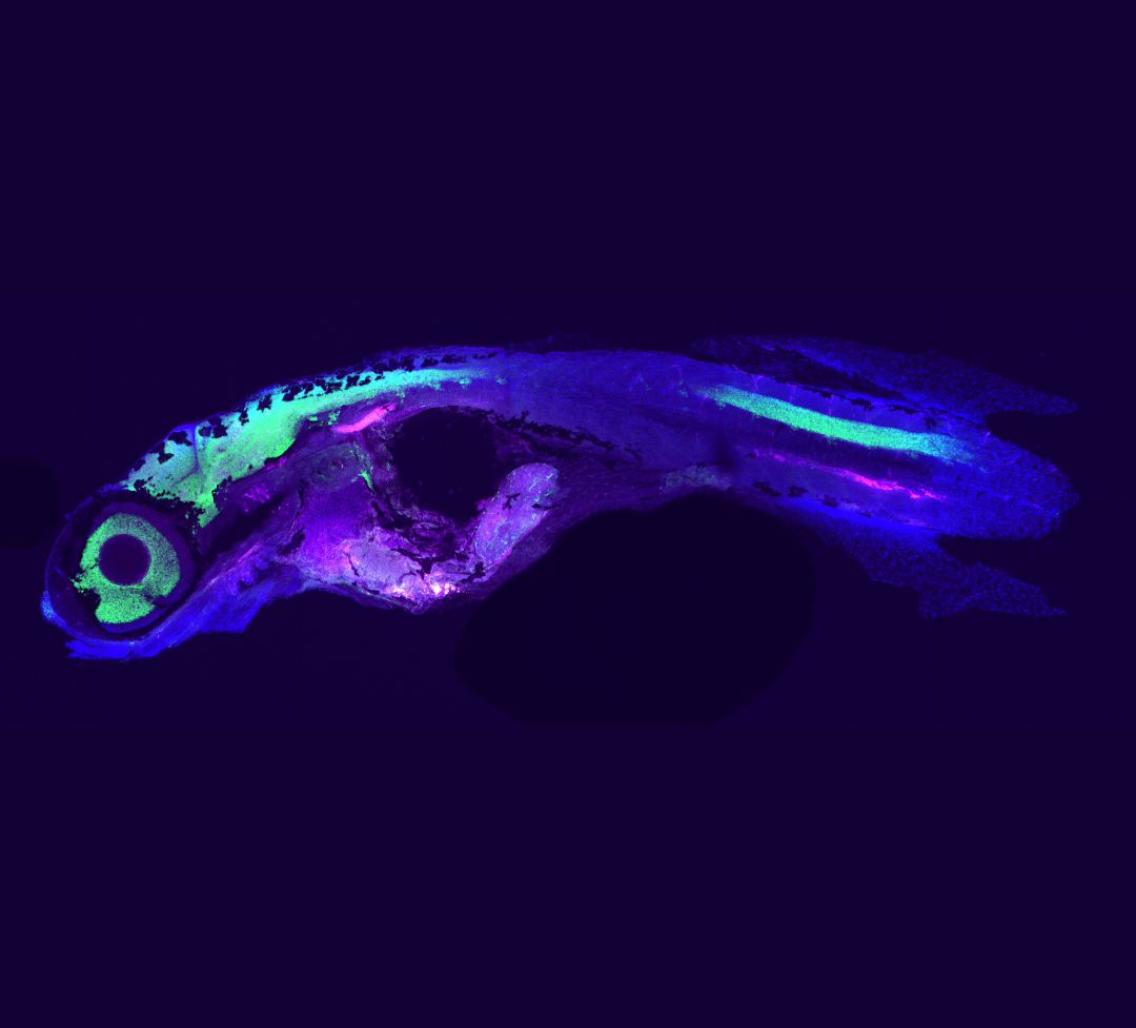

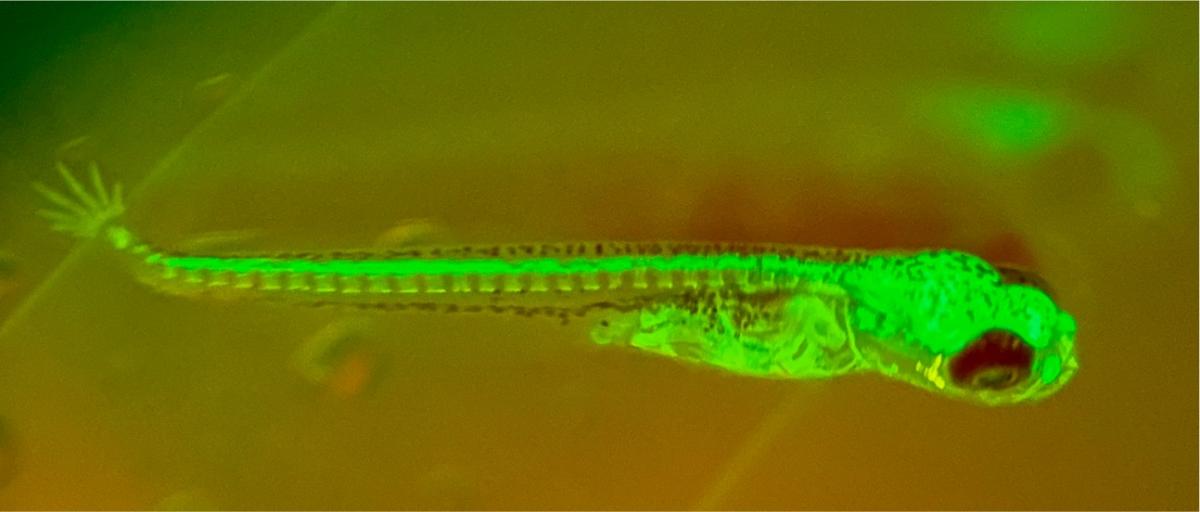

So far, they have succeeded in inserting a fluorescent protein into different regions of the killifish genome to create animals with glowing brains and glowing eyes. They even managed to create animals where only a specific subset of the neurons light up. And throughout their experiments, they didn’t observe any “off-target effects,” or mutations in unintended places—a major risk with CRISPR.

A fluorescent killifish fry demonstrates the ability of researchers to introduce new genes into the kilifish genome -- in this case a fluorescent protein. Image credit: the Brunet Lab, Stanford.

A sweet spot for aging biology

Anne Brunet, the Michele and Timothy Barakett Professor in the Department of Genetics. Image credit: Steve Fisch for the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

The new technique opens lines of research that would previously have been impossible. “The killifish is at a sweet spot for aging biology,” said Brunet, who is the Michele and Timothy Barakett Professor in the Department of Genetics and the new study’s corresponding author. Since they live about a tenth as long as zebrafish, a more common aquatic model organism, studying them involves much less waiting around.

It might seem counterintuitive to use an animal whose lifespan is measured in months to study diseases that take decades to manifest in humans. But many parts of the aging process, scientists believe, are genetically programmed—in killifish, they just happen much, much earlier than in humans.

Seen from this perspective, the killifish is a shortcut to obtaining the sort of biological environment you’d find in a mouse after three years, or a human after 80. And unlike other short-lived animals, such as fruit flies, killifish are vertebrates. That means that their brains and immune systems bear much more resemblance to those of mammals—and, seeing as immune cells have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, that’s a huge advantage for aging research.

With this new gene insertion technology, scientists will at last be able to put human gene mutations linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases into killifish and see what happens. Observing how a gene of choice behaves in an aging vertebrate body used to take years—now, the same experiments can be accomplished in months.

Karl Deisseroth, the D.H. Chen Professor in the departments of Bioengineering and of Psychiatry. Image Credit: the Deisseroth Lab, Stanford.

That’s far from the only application of this new approach. Deisseroth, who is the D.H. Chen Professor in the departments of Bioengineering and of Psychiatry and co-mentors Bedbrook and Nath with Brunet, is looking forward to using CRISPR to manipulate brain activity in killifish using optogenetics, a technique his team famously pioneered that allows scientists to activate or deactivate particular populations of neurons using light. The technique requires splicing genes for custom light-sensitive proteins into an animal’s genome, and so had previously been impossible in killifish.

Now Deisseroth said he hopes to investigate hypotheses that link neurodegenerative diseases to brain activity—and perhaps uncover circuits linked to brain resilience in killifish and other animals, as part of the Knight Initiative-funded project.

“Nature can always spring surprises on you,” said Deisseroth, “so I don’t want to act as if we’ve solved everything. But we’ve taken a big step toward our goal.”

Funding Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, the Iqbal Farrukh & Asad Jamal Center for Cognitive Health in Aging, and the Knight-Hennessy Scholars program at Stanford University and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01AG063418, T32 AG000266, T32 AG0047126), the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the Simons Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub – San Francisco, and the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation. The authors declare no competing interests.