Groove is in the brain: Music supercharges brain stimulation

Music affects us so deeply that it can essentially take control of our brain waves and get our bodies moving.

Now, neuroscientists at Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute are taking advantage of music’s power to synchronize brain waves to boost the effectiveness of a technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a promising tool for both basic brain research and treating neuropsychiatric disorders.

Specifically, institute affiliate Jessica Ross and colleagues used TMS pulses to induce movements in people's hands—a common testing ground for new ideas in the field. By carefully timing those pulses to music, the team found they could double the impact of TMS.

“Because there's this really strong connection to movement, music can engage motor pathways in the brain. If you're listening to a certain kind of rhythm, there are going to be very specific times at which your brain is most ready for the TMS effect,” said Ross, an instructor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford Medicine.

Although more work needs to be done, she said, the results could pave the way for a more ambitious goal: amplifying the effects of TMS on depression, chronic pain, and other neurological conditions.

“Because there's this really strong connection to movement, music can engage motor pathways in the brain. If you're listening to a certain kind of rhythm, there are going to be very specific times at which your brain is most ready for the TMS effect."

Jessica Ross

Instructor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

The electromagnetic brain

The new study, published July 7 in Human Brain Mapping, got its start last year with a pilot grant from the Koret Human Neurosciences Community Laboratory at Wu Tsai Neuro. The lab supports researchers across campus who are interested in applying TMS and another technology, electroencephalography (EEG), to their work.

EEG is an observational tool that tracks average electrical signals across thousands of neurons in the brain. Those averages show up on an EEG readout as waves that reflect shifting patterns of brain activity.

TMS, on the other hand, is a method to reshape brain activity with magnetic pulses. TMS researchers trying out new ideas often start by targeting the primary motor cortex, a brain region responsible for coordinating movement. Doing so sends easy-to-measure electrical impulses down our nerve fibers, causing specific muscles to twitch, which helps researchers calibrate the strength and targeting of their brain stimulation.

Stanford researchers have pioneered using TMS to treat depression and obsessive compulsive disorder by targeting the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s thought center. For all their promise, however, these treatments can be inconsistent and tricky to calibrate, motivating researchers like Ross to find ways to get more out of the technique.

Feelin’ groovy

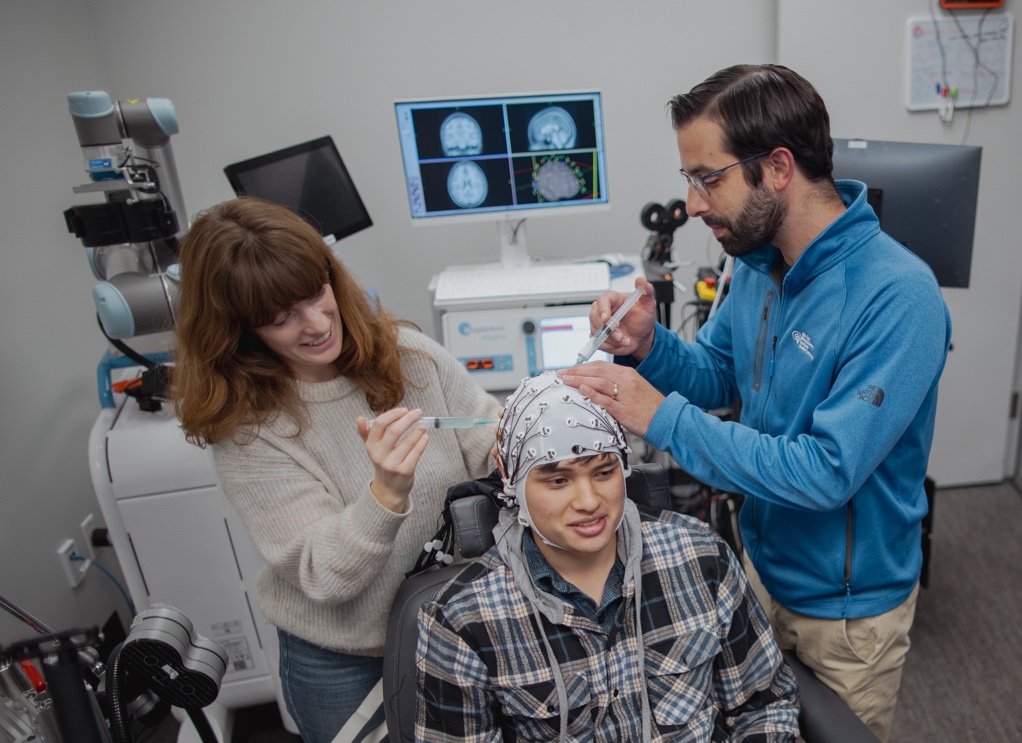

In their effort to use musical rhythm to boost the efficacy of TMS, Ross and her team first needed to see if they could sync up patterns of brain activity in the primary motor cortex to music. They outfitted 27 people with EEG caps at the Koret Lab so they could track brain waves in the motor cortex. Then, they turned on the music—Leela James’s “Music,” Billy Preston’s “Outa-Space,” and JoJo’s “Baby It’s You.”

Participants’ brain waves quickly got into the groove. In particular, the researchers found that brain waves in primary motor cortex consistently dipped around 200 milliseconds before a dominant beat.

This gave the researchers an opportunity. Previous studies have shown that dips in motor cortex brain waves happen when we're most prepared to move. Ross and her team suspected the brain might be most susceptible to TMS at those moments as well.

TMS aimed at the primary motor cortex bumps up electrical activity in muscles, so the team tested their idea by tracking electrical signals in 19 participants’ hands while undergoing TMS. Some of the time, the researchers played music and sent TMS pulses into the primary motor cortex just ahead of the beat. At other times, the researchers either timed the pulses on the beat or used standard TMS without music.

The result: Music increased what TMS could do by 77% when timed with the dip just ahead of the beat. The timing itself mattered, too. Sending pulses 200 milliseconds ahead of the beat increased the effect by 37% compared to timing them right on the beat.

Mood music

Those observations could have implications beyond making your hand twitch, said senior author Corey Keller, a Wu Tsai Neuro affiliate and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medicine.

“TMS is a really valuable tool that has been translated to clinical use, but there's a lot that we are still learning about how best to apply it,” Keller said. “So this idea that we can harness and manipulate the brain state in a way that improves treatment outcomes is something that we're currently exploring.”

Ross and Keller are most excited about the possibilities for treating psychiatric conditions. Music can also synchronize brain waves in the prefrontal cortex, and the pair are now studying whether that synchronization could lead to improvements to prefrontal TMS. If so, that could eventually help doctors enhance the ability of TMS to treat depression and other disorders.

That possibility could also lead to a kind of personalized medicine where different songs and grooves could be tailored to individual patients, Keller said. Perhaps one day you could just tell the TMS DJ to play your favorite tune.

Publication Details

Research Team

Study authors were Jessica Ross and Corey Keller from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford Medicine, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Healthcare System and the Sierra Pacific Mental Illness, Research, Education, and Clinical Center; Lily Forman, Umair Hassan, hristopher C. Cline, Sara Parmigiani, Jade Truong, James W. Hartford, and Nai-Feng Chen from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford Medicine and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute; Juha Gogulski from from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford Medicine, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, and Aalto University School of Science; Takako Fujioka from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and the Stanford University Department of Music, Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA); Scott Makeig from the University of California, San Diego; and Alvaro Pascual-Leone from Harvard Medical School and Hinda and Arthur Marcus Institute for Aging Research.

Research Support

This research was supported by the Koret Human Neurosciences Community Laboratory at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health R01MH126639), and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists. Ross was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Medical Research Service of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Sierra-Pacific Data Science Fellowship. Gogulski was supported by personal grants from Orion Research Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, and Emil Aaltonen Foundation. Pascual-Leone was partly supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG076708), Jack Satter Foundation, and BrightFocus Foundation.

Competing Interests

Ross and Keller are listed as inventors on United States Patent No. US-20240285964-A1. Keller holds equity in Alto Neuroscience Inc. Pascual-Leone serves as a paid member of the scientific advisory boards for Neuroelectrics, Magstim Inc., TetraNeuron, Skin2Neuron, MedRhythms, and AscenZion. He is co-founder of TI solutions and co-founder and chief medical officer of Linus Health. He is also listed as an inventor on several issued and pending patents on the real-time integration of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging and applications of noninvasive brain stimulation in various neurological disorders; as well as digital biomarkers of cognition and digital assessments for early diagnosis of dementia. No other conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.