Technique developed by Stanford scientists could lead to new treatments for pain

By Amy Adams

The mice in Scott Delp's lab, unlike their human counterparts, can get pain relief from the glow of a yellow light.

Right now these mice are helping scientists to study pain – how and why it occurs and why some people feel it so intensely without any obvious injury. But Delp, a professor of bioengineering and mechanical engineering, hopes one day the work he does with these mice could also help people who are in chronic, debilitating pain.

"This is an entirely new approach to study a huge public health issue," Delp said. "It's a completely new tool that is now available to neuroscientists everywhere." He is the senior author of a research paper published Feb. 16 in Nature Biotechnology.

A switch for pain

The mice are modified with gene therapy to have pain-sensing nerves that can be controlled by light. One color of light makes the mice more sensitive to pain. Another reduces pain. The scientists shone a light on the paws of mice through the Plexiglas bottom of the cage.

Graduate students Shrivats Iyer and Kate Montgomery, who led the study, say it opens the door to future experiments to understand the nature of pain and also touch and other sensations that are part of our daily lives but little understood.

"The fact that we can give a mouse an injection and two weeks later shine a light on its paw to change the way it senses pain is very powerful," Iyer said.

For example, increasing or decreasing the sensation of pain in these mice could help scientists understand why pain seems to continue in people after an injury has healed. Does persistent pain change those nerves in some way? And if so, how can they be changed back to a state where, in the absence of an injury, they stop sending searing messages of pain to the brain?

Leaders at the National Institutes of Health agree the work could have important implications for treating pain. "This powerful approach shows great potential for helping the millions who suffer pain from nerve damage," said Linda Porter, the pain policy adviser at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and a leader of the NIH's Pain Consortium.

"Now, with a flick of a switch, scientists may be able to rapidly test new pain relieving medications and, one day, doctors may be able to use light to relieve pain," she said.

Accidental discovery

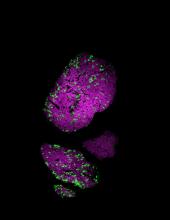

The researchers took advantage of a technique called optogenetics, which involves light-sensitive proteins called opsins that are inserted into the nerves. Optogenetics was developed by a colleague of Delp, Karl Deisseroth, a co-author of the journal article. He has used the technique as a way of activating precise regions of the brain to better understand how the brain functions. Deisseroth is a professor of bioengineering, psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

Delp, who has an interest in muscles and movement, saw the potential for using optogenetics not just for studying the brain – interesting though those studies may be – but also for studying the many nerves outside the brain. These are the nerves that control movement, pain, touch and other sensations throughout our body and that are involved in diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's Disease.

A few years ago Stanford Bio-X, which encourages interdisciplinary projects like this one, supported Delp and Deisseroth in their efforts to use optogenetics to control the nerves that excite muscles. In the process of doing that work, Delp said, his student at the time, Michael Llewellyn, would occasionally find that he'd placed the opsins into nerves that signal pain rather than the ones that control muscle.

That accident sparked a new line of research. Delp said, "We thought 'wow, we're getting pain neurons, that could be really important.'" He suggested that Montgomery and Iyer focus on those pain nerves that had been a byproduct of the muscle work.

A faster approach

A key component of the work was a new approach to quickly incorporate opsins into the nerves of mice. The team started with a virus that had been engineered to contain the DNA that produces the opsin. Then they injected those modified viruses directly into mouse nerves. Weeks later, only the nerves that control pain had incorporated the opsin proteins and would fire, or be less likely to fire, in response to different colors of light.

The speed of the viral approach makes it very flexible, both for this pain work and for future studies. Researchers are developing newer forms of opsins with different properties, such as responding to different colors of light. "Because we used a viral approach we could, in the future, quickly turn around and use newer opsins," said Montgomery, who is a Stanford Bio-X fellow.

This entire project, which spans bioengineering, neuroscience and psychiatry, is one Delp says could never have happened without the environment at Stanford that supports collaboration across departments. The pain portion of the research came out of support from NeuroVentures, which was a project incubated within Bio-X to support the intersection of neuroscience and engineering or other disciplines. That project was so successful it has spun off into the Stanford Neurosciences Institute, of which Delp is now a deputy director.

Delp said there are many challenges to meet before results of these experiments – either new drugs based on what they learn, or optogenetics directly – could become available to people, but that he always has that as a goal.

"Developing a new therapy from the ground up would be incredibly rewarding," he said. "Most people don't get to do that in their careers."

Delp and Deisseroth have started a company called Circuit Therapeutics to develop therapies based on optogenetics.