Respect your biological clock

We've probably all heard of circadian rhythms, the idea that our bodies have biological clocks that keep track of the daily cycle, sunrise to sunset. Maybe we've even heard that it's these biological rhythms that get thrown off when we travel across time zones or after daylight savings.

So on one hand, it's cool that our body keeps track of what time it is, but today our question is just how important are our circadian rhythms to our health and wellbeing? Do we need to be paying attention to these daily rhythms and what happens if we don't?

So we asked Stanford circadian biology expert, Erin Gibson.

Listen to the full episode below, or SUBSCRIBE on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music or Stitcher. (More options)

Links

References

- Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan

- Circadian disruption and human health: A bidirectional relationship

- The arrival of circadian medicine

Episode Credits

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne, with production assistance by Morgan Honaker and Christian Haigis, and hosted by Nicholas Weiler. Cover art by Aimee Garza.

Episode Transcript

Nicholas Weiler (00:08):

This is From Our Neurons to Yours, a podcast from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University at Stanford University. On this show, we crisscross scientific disciplines to bring you to the frontiers of brain science. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler. Here's the sound we created to introduce today's episode.

(01:09)

Perhaps that is the sound of our circadian rhythms. We've probably all heard of circadian rhythms, the idea that our bodies have biological clocks that keep track of the daily cycle, sunrise to sunset. Maybe we've even heard that it's these biological rhythms that get thrown off when we travel across time zones or after daylight savings.

(01:28)

So on one hand, it's cool that our body keeps track of what time it is, but today our question is just how important are our circadian rhythms to our health and wellbeing? Do we need to be paying attention to these daily rhythms and what happens if we don't? So we asked Stanford circadian biology expert, Erin Gibson.

Erin Gibson (01:47):

I'm Erin Gibson. I am an assistant professor here in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences as well.

Nicholas Weiler (01:54):

The question I want to ask you today is why should we pay attention to our circadian rhythms? And maybe first we should talk a little bit about the bigger picture, what are circadian rhythms?

Erin Gibson (02:04):

So the reason we should care about them is because of the old adage, timing matters. And in biology and physiology, the same is true. Timing really matters. If you think about things like digestion, right? When you are awake, that's when you're eating. That's when you need all of the systems that regulate digestion to be important.

(02:25)

But you don't need those systems activated at night when you're sleeping. Urine production is higher during the day because you're drinking more water, you're running around, it's easier to get to a bathroom. At night, you don't want to be getting up all the time to go to the bathroom. So your urine production decreases at night.

(02:42)

Circadian means approximately daily, so approximately 24 hours, virtually every cell in your body has a little 24-hour clock that's regulated at the genetic level. Those little clocks, cellular clocks can be synchronized to each other so that whole organ systems can oscillate on a 24-hour clock,.

(03:03)

And then those organ systems can be tuned to the 24-hour environment that we live in. Light, dark information goes through your eye. And so what circadian system allows for you to do is optimize your biology so that processes are happening at the proper time of day.

Nicholas Weiler (03:22):

Got it. So making sure all the right things are going on at the right time.

Erin Gibson (03:25):

Exactly.

Nicholas Weiler (03:25):

Throughout your body.

Erin Gibson (03:26):

Yep.

Nicholas Weiler (03:27):

Well, you mentioned that circadian rhythms are tied to light and dark, but most of us don't run on a sort of sunrise to sunset schedule these days. Have things like the standardized 24 hour day and electric lighting everywhere in our lives, have those changed how our circadian rhythms work?

Erin Gibson (03:42):

Dramatically. So the advent of industrialization and 24/7 electricity really has in many ways wreaked havoc on our biology, because now that environmental information is not as useful to us. Not only does it affect your misalignment of your endogenous circadian rhythm with the environment, but it also has afforded us opportunities to work outside of hours that we normally should be working.

(04:09)

Right? So shift work became a thing you could do. Trans meridian travel on airplanes and jet lag became a thing you could do. And all of those events are what we term circadian misalignments. So now your internal circadian clocks are no longer matching the external rhythms.

(04:28)

And it's actually been shown that things like shift work are really detrimental and associated with a whole host of pathologies. Everything from higher rates of diabetes to cancer, psychological psychiatric disorders like depression. And actually the World Health Organization has classified shift work as a carcinogen.

Nicholas Weiler (04:49):

Really?

Erin Gibson (04:49):

Yes.

Nicholas Weiler (04:50):

Wow.

Erin Gibson (04:51):

And then the same thing is true with trans meridian travel. Right? So we all know how awful you feel if you fly six time zones away, and actually a one-hour time change. So say you were to fly from California all the way to New York, that's three hours. You don't think it's dramatic. It actually takes your biological clocks one day to adjust to a one-hour time change.

Nicholas Weiler (05:13):

Wow.

Erin Gibson (05:14):

And we have a new layer of complexity recently with our phones and our screens. And we all tend to stay up on screens until right before we want to go to bed. And that also disrupts your circadian rhythms because light suppresses melatonin.

Nicholas Weiler (05:30):

So we're shining these lights in our faces, and we're right when our body is trying to shift.

Erin Gibson (05:36):

When our body is trying to start winding up to go to bed by increasing melatonin secretion. And then you're blocking that because light literally blocks the production of melatonin, and that disrupts the timing of your system.

Nicholas Weiler (05:49):

I mean, it sounds like there are all kinds of ways in which we are ignoring this circadian biology. We are just sort of blasting through it with our technological like, "I can do whatever I want."

Erin Gibson (05:59):

Yeah.

Nicholas Weiler (06:01):

What's going on in the brain when these circadian rhythms get thrown off?

Erin Gibson (06:05):

Yeah. So a couple of different things. It messes with metabolic support of cells in the brain. It can mess with clearance of waste that happens within the brain. We found in a study that I led many years ago now, that essentially using a rodent model of chronic jet lag. The equivalent of flying from Chicago to London every few days resulted in the decreased production of new neurons in the memory center of your brain.

(06:33)

And that resulted in memory deficits within these rodents that lasted for long after they recovered actually from the jet lag. And so some of the strongest evidence that circadian misalignment and circadian disruption affects the brain is actually in the psychiatric fields. Many people now think that depression is actually a circadian misalignment disorder.

Nicholas Weiler (06:58):

Wow. Yeah, because sleep disruption is, I think, also associated with depression. And so it's one of those things where it's hard to tell what's the cause and what's the effect if circadian disruption can also potentially lead to the psychiatric disorder.

Erin Gibson (07:11):

It is. And sleep is regulated by the circadian system. So two things regulate sleep. One is you have a homeostatic drive to sleep. You can only stay awake for so long before your body needs sleep. But the timing of sleep matters.

(07:26)

And so there's a circadian component. It's the convergence of sort of this homeostatic drive and this circadian drive that is what initiates sleep. And people will think, "Oh, I slept eight hours. I'm a shift worker. I went to bed at 7:00 AM and I still slept at eight hours, so I got the same amount of sleep."

(07:44)

But the quality of that sleep is not the same because your body is not timed properly to sleep at that time of day. You have all these systems that want to be activated because it's daytime. You're supposed to be doing other things and now you're sleeping. And so disentangling sleep in circadian can be very difficult because circadian rhythms regulate sleep.

Nicholas Weiler (08:04):

Well, this clearly is a big issue for people who do shift work, people who are traveling on airplanes all the time. I mean, what can we do to better respect our circadian rhythms?

Erin Gibson (08:14):

So there's a couple of really easy things you can actually do to sort of retrain or re-sync up the environment with your internal biological clocks. One is getting bright light in the morning within an hour of waking. And by bright light, we mean sunlight. Not your cell phone. Yeah. You need a more powerful light.

(08:33)

So going on a 20-minute walk outside, not wearing your sunglasses, helps to give your body that in training cue. The other good thing is on the other end of the day, when you are wanting to go to bed, so one of the cues that we always talk about as humans, but related to sleep is melatonin. We say melatonin helps with sleep. Melatonin is actually not a sleep hormone.

(08:55)

So what melatonin actually is a timing cue. Because like I said, light through the eye actually suppresses the production of melatonin. And so at night you start getting a natural circadian driven increase in melatonin that gradually starts increasing about two hours prior to when your sleep onset should occur.

(09:16)

And then it increases its rise and its highest at night when you're sleeping. But if you were to go into your bathroom and turn the light on in the middle of the night, that would crash your melatonin. And now that timing cue is off because now it's suppressed when it should be high and it has to build back up.

(09:33)

And so not only is it important to get really bright light in the morning when you wake up, but it's important to block bright light at night before you go to bed. And so doing things like dimming the lights in your house, not being on your phone right up until you go to bed, sort of giving your body those cues that it's nighttime, it's dark, it's time to start settling down.

Nicholas Weiler (09:57):

And of course, those are things that's great to do if you have the luxury of doing them. But there's also the issue of the people who are doing shift work, and so I may not have those options.

Erin Gibson (10:06):

Yeah. So that's where it gets more complicated. And there are devices out there that allow you to sort of regulate light sources better, and those are somewhat effective. There's light boxes that you can expose yourself to that give you the proper wavelengths of light and the proper lux or intensity of light. Those boxes have been used in things like seasonal effective disorder as well.

(10:26)

We now have these glasses that block certain wavelengths of light, like blue light because that seems to be more suppressive of circadian rhythms. And if you are say, for example, taking trans meridian travel or you're trying to realign your rhythms, that taking melatonin in your new time zone two hours prior to the time you want to go to bed can adjust to those rhythms faster than they would naturally.

(10:48)

But in general, unfortunately, there's not too much we can do. One of the things we do know with shift work is that if you are a shift worker, one of the worst things you can do is switch between day and night shifts. That's really hard for your body because now then it's constantly shifting.

(11:03)

Whereas if you are a more of a chronic nighttime shift worker with time, some of the rhythms, not all rhythms, but some rhythms can eventually adjust to that new schedule. But once you switch back to day work, everything sort of goes up in the air again. And so consistency matters a lot within circadian biology.

Nicholas Weiler (11:24):

Well, we just have a couple minutes left. I want to go back and dig just a little bit more into the biology, if you don't mind.

Erin Gibson (11:29):

Yeah.

Nicholas Weiler (11:30):

So as part of this question, why should we be paying more attention to our circadian rhythms, can you give us just a sampling of some of the things we know get affected by our circadian rhythms in our biology, and particularly in our brain?

Erin Gibson (11:41):

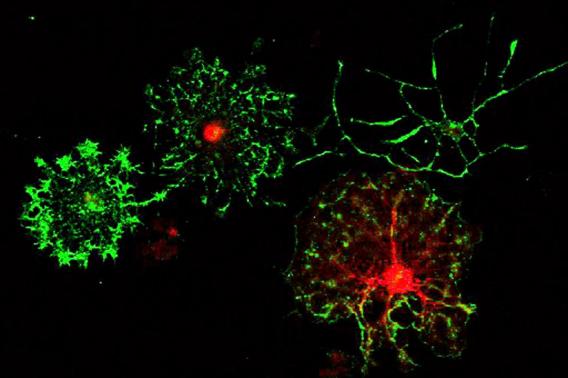

Yeah. So pretty much everything is controlled by the circadian clock. We have not really identified cell types within the brain or body that aren't regulated on a circadian cycle. In the brain, I think where the biggest hole of our understanding of circadian biology really lies in the fact that your brain is made up of two main classes of cell types, neurons, which is what most people think about when we talk about the brain.

(12:04)

But there's also a subclass of neurons called glia. And glia are the workhorses of the brain. And they're actually the majority of the cells in the brain. Without these cells, neurons cannot function. And it sort of lends themselves to being regulated by the circadian system.

(12:20)

But we know actually very little about what role the circadian system is playing within these cells. And that's actually one of the things our lab focuses on, is trying to understand how this really dynamic molecular circadian clock regulates these glia cells in the brain during development as well as dysregulation and the role it might play in various brain disorders.

Nicholas Weiler (12:40):

Yeah. Well, that was sort of the answer to my last question. Is there one thing that drives your curiosity? Why do you think people should be paying attention to these rhythms?

Erin Gibson (12:48):

Yeah. So the more you look at circadian rhythms, the more you look at brain disorders, the more you realize that virtually every brain disorder from neurodevelopmental, like autism to neuropsychiatric, like schizophrenia and bipolar to neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer's and multiple sclerosis, they all have very strong circadian and sleep phenotypes.

(13:10)

It is a hallmark of almost all pathologies related to the brain. And part of the reason I think for that is because it is so important that all of these complex biological and physiological processes happen at the right times a day. And in a lot of these disorders, when those rhythms get disrupted, it either could potentially cause some of these disorders or exacerbate them.

(13:38)

And we know that the more misaligned you are, the worse a lot of these disorders get. And I think one of the reasons that we have not as a community made as much progress on a lot of the brain disorders that we study is because, one, we ignore timing, not only in terms of the role it plays in the underlying biology of these disorders, but also in how we medically treat these disorders.

(14:01)

Because giving medications at certain times a day are going to have different effects. Medicine is metabolized and your metabolic function, whether it's cleared by your kidney or your liver, those things are regulated in a circadian manner. So for example, we study chemotherapy neurotoxicity, and we find if we give the same dose of a chemotherapeutic agent, twice as much will get into a mouse brain in the morning as it does in the evening.

Nicholas Weiler (14:28):

Wow. Twice as much.

Erin Gibson (14:28):

Twice as much.

Nicholas Weiler (14:29):

So it depends on exactly when you give it. That's going to affect.

Erin Gibson (14:31):

Right. Exactly. And so not only will it maybe affect how it's administered and how it's up-taked, but how it's metabolized and how it's cleared. And so it's really important to understand this timing mechanism, not only in terms of the disorder itself and the cause and the progressiveness of the disorder, but also in the treatment.

Nicholas Weiler (14:50):

Wow. Yeah. Well, that's a lot to think about. There's clearly a whole lot more here that we could discuss, but I just want to thank you for joining us on the show.

Erin Gibson (14:59):

Yeah, thank you for having me. Always happy to talk about circadian rhythms.

Nicholas Weiler (15:03):

Absolutely. Well, hopefully we can have you back and we can talk even more.

Erin Gibson (15:06):

Sounds great.

Nicholas Weiler (15:16):

Thanks so much again to our guest, Erin Gibson. For more info about her lab's, work on circadian biology and glia, check out the links in the show notes.

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne with Production assistance by Morgan Honaker and Christian Haigis. I'm Nicholas Weiler. See you next time.