How Bodies Get Smarts: Simulating the Evolution of Embodied Intelligence

Does the development of an artificial intelligence also require an artificial body to go with it?

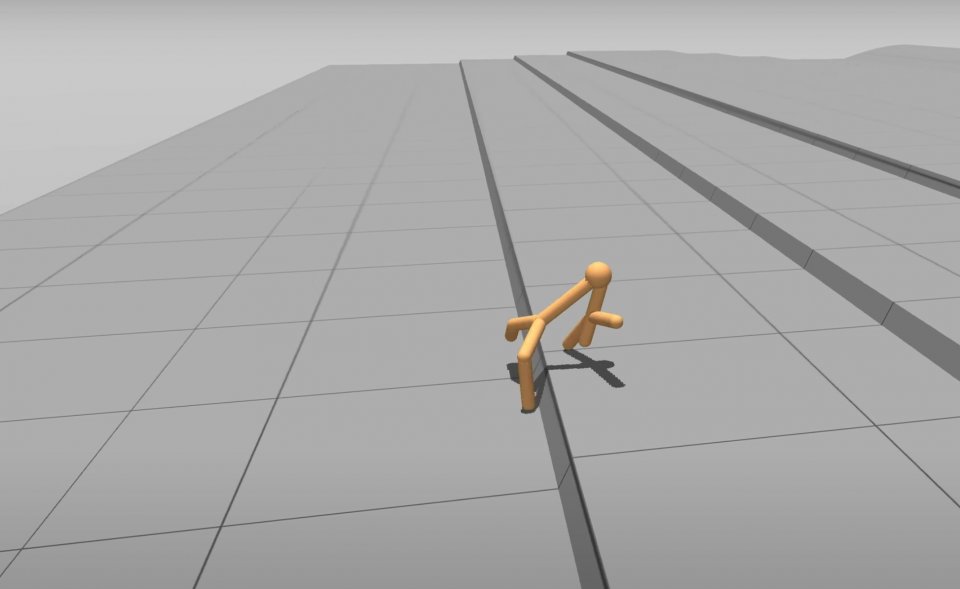

To study this question, Wu Tsai Neuro affiliates Fei-Fei Li, Surya Ganguli and colleagues created simple artificial animals, dubbed "unimals", and placed them in simulated playground to study their ability to learn and develop.

The research was written up by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI):

“We're often so focused on intelligence being a function of the human brain and of neurons specifically,” says Fei-Fei Li, a member of the research team and co-director of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI). “Viewing intelligence as something that is physically embodied is a different paradigm.”

Their findings, detailed in the journal Nature Communications, suggest embodiment is key to the evolution of intelligence: The virtual creatures’ body shapes affected their ability to learn new tasks, and morphologies that learn and evolve in more challenging environments, or while performing more complex tasks, learn faster and better than those that learn and evolve in simpler surroundings. In the study, unimals with the most successful morphologies also picked up tasks faster than previous generations — even though they began their existence with the same level of baseline intelligence as those that came before.

“To our knowledge, this is the first simulation to show that what you learn within a lifetime can be sped up just by changing your morphology,” says study co-author Surya Ganguli, an associate professor of applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences and an associate director at HAI.