Big Ideas in Neuroscience tackle brain science of everyday life and more

Sometimes the worst part of getting sick isn’t the runny nose, the headaches or the grumpy stomach—it’s the fatigue, that hazy feeling that you probably don’t have the energy to make a cup of coffee, let alone make it to work.

Most of the time, that fatigue passes, but for some people it can last months or years—a stark reality highlighted by the emergence of long COVID.

But why we get fatigued—and why that fatigue can last long after an infection is gone—remains unclear. In large part, that’s because no one is quite sure how our brains sense we’re ill in the first place. Answering these questions requires wide-ranging collaboration between experts in neurobiology, immunology, pathology, and more, disciplines that all too often remain within traditional departmental silos.

Now, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford has convened a cross-disciplinary research team to tackle this problem—alongside four other major questions in the field—as part of its Big Ideas in Neuroscience Program.

Since 2014, the Big Ideas program has been challenging Stanford researchers from wide-ranging scientific backgrounds to come together, break down barriers and tackle some of the biggest questions in neuroscience. Big Ideas projects have covered everything from brain development to addiction to the possibility of making our brains young again—an endeavor that laid the groundwork for the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience housed at Wu Tsai Neuro.

For its third round of Big Ideas projects, Wu Tsai Neuro is supporting five new teams with equally ambitious plans for the field.

Three of these projects reflect a growing emphasis on neuroscience questions that explore issues relevant to our daily lives—not only how sickness affects our behavior, but also how we decipher and produce language and how pregnancy shapes and is shaped by the brain. Other projects continue the tradition of applying interdisciplinary expertise to devise new technologies to accelerate neuroscientific research, including one team that will engineer genetic tools to make the living mouse brain clear as glass and another team that will use genetics and artificial intelligence to better understand how the brain responds to stress.

“I’m proud that we’re funding such a wide spectrum of research,” said Kang Shen, the Vincent V.C. Woo Director of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the Frank Lee and Carol Hall Professor, a professor of biology in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, and a professor of pathology in the Stanford School of Medicine. “These projects include faculty from ten departments in Stanford Humanities and Sciences, Medicine, and Engineering. It’s a testament to the breadth of faculty expertise Wu Tsai Neuro covers. That’s the essence of the Institute.”

Life and how we live it

A central goal of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute is to use our growing knowledge of how the brain gives rise to mental life and behavior to promote human well-being. Three of this round’s Big Ideas projects will tackle that goal head on.

The Stanford Neuro-Pregnancy Initiative

One such effort will study how the brain and body interact during pregnancy, something that’s received relatively little attention until now.

Indeed, researchers don’t know much about how the brain changes during pregnancy or how that might be connected to other physiological or behavioral changes, said Nirao Shah, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and of neurobiology at Stanford Medicine who spearheaded the effort.

Shah, an expert in sex differences in behavior, said the team was motivated by links they’d seen between gene expression and behavior over the course of the ovulatory cycle in mice. That got them wondering whether there were similar links in pregnancy, “but the more we poked the research literature, the more we realized that not much is known about how the brain coordinates pregnancy,” Shah said.

Shah's colleague Longzhi Tan agreed. “This has barely been measured before,” said Tan, an assistant professor of neurobiology at Stanford Medicine.

To learn more, Shah will work with Tan, who studies the genomic structure and function of brain cells, and Katrin Svensson, an associate professor of pathology whose work focuses on circulating hormones that affect our physiology and metabolism.

By combining their diverse expertise, the researchers hope to pave the way for therapeutics that could treat a wide variety of pregnancy-related concerns, such as miscarriage, severe nausea, preeclampsia and post-partum depression.

A New Precision Neuroscience of Language

A second team will tackle something so commonplace most of us don’t think about it: language.

“My dream is that we’re going to have two outcomes from this,” said Laura Gwilliams, a faculty scholar at Wu Tsai Neuro and Stanford Data Science and an assistant professor of psychology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “One is that we’re going to be able to provide, for the first time, a comprehensive theory of language neuroscience, from the single neuron level to the whole-brain level.

“The second is the translational outcome. We want to use our basic science results to guide optimal implants for brain-computer interfaces so that patients who can’t speak can communicate again,” Gwilliams said.

There’s a critical need for both pieces. Around a quarter of a million people have a communication disorder stemming from neurodegenerative disease, strokes, cerebral palsy, and more. But to understand and treat those disorders, researchers need to bridge gaps between the different scales at which they study language.

“The neural code for language is implemented at the single-cell level all the way up to brain-wide circuits, requiring neural measurements that operate at each commensurate scale,” said Gwilliams.

To link those together, Gwilliams, who studies speech comprehension, is teaming up with brain-computer interface experts Jaimie Henderson, the John and Jene Blume - Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor and a professor of neurosurgery at Stanford Medicine, and Frank Willet, an assistant professor of neurosurgery at Stanford Medicine, as well as Cory Shain, an assistant professor of linguistics in Stanford Humanities and Sciences who uses neuroimaging and computational methods to study language in the brain. Together, this Big Ideas team will conduct experiments using multiple techniques simultaneously, which will help them integrate what’s known about language processing across scales. That could in turn aid clinical efforts to restore speech to people with paralysis or other conditions.

Immunomodulation of gut-brain interactions

Then there’s that fatigue project.

The idea originated at the 2024 Wu Tsai Neuro retreat, during which the institute challenged the research community to identify major open questions in the field that a cross-disciplinary Big Ideas project could address. One brainstorming session brought together Julia Kaltschmidt, a Wu Tsai Neuro Faculty Scholar and professor of neurosurgery at Stanford Medicine who studies neural circuits of the gut, and Luis de Lecea, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medicine who specializes in the brain circuits of sleep and wakefulness. As they got talking, they realized there were potential connections between sleep, sickness, and the gut that were worth investigating.

When the institute sent out its call for new Big Ideas in Neuroscience proposals, “Luis and I emailed each other at the exact same time,” said Kaltschmidt.

She and de Lecea recruited Christoph Thaiss, a newly hired assistant professor of pathology at Stanford Medicine and core investigator at the Arc Institute in Palo Alto who specializes in gut–brain interactions. Together they’ll apply their knowledge of disease, sensory systems, sleep, and the gut’s nervous system to better understand how illness shapes our behavior—including sleep—and lay the groundwork for potential treatments.

“If you understand what the mechanism is—what the molecules are that are involved in sickness and fatigue—maybe you can harness those and find a cure,” Kaltschmidt said.

New horizons

This year’s round of Big Ideas will also back two ambitious efforts to develop cutting-edge tools to expand the frontiers of neuroscience.

In Vivo Functional Genomics and Foundational Virtual Models of Brain Homeostasis and Resilience

One team aims to tackle the mystery of brain cells’ remarkable resilience to stress—and how it begins to fail with age—using cross-species genomics and AI.

Unlike many parts of your body, in which cells die off regularly and are replaced, you are born with all the brain cells you’ll ever need. This means brain cells need to be tough and resilient to all kinds of stressors. Researchers have long puzzled over how the brain accomplishes this at a molecular level and how these mechanisms of resilience may start to fail with age, a key suspect in the rise of neurodegenerative disease and cognitive decline.

Currently, no one has quite the right tools to address this problem, but a Big Ideas team co-sponsored by the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience comprising neurobiologist Tom Clandinin, developmental biologist Will Allen, and geneticist Xiaojie Qiu, all based at Stanford Medicine, are taking on the challenge.

They’re working to adapt genetic methods typically used in mice into fruit flies, in which genetic screens and other methods can be carried out much more quickly owing to the flies’ short lifespan. Then, they’ll study which genes might affect the fly brains’ stress responses and build artificial intelligence models to translate their results back into mice. Eventually, they hope to translate their results into humans to better understand the brain’s response to stress.

“Stressors are an inevitable part of life,” said Clandinin, the Shooter Family Professor and a professor of neurobiology at Stanford Medicine. “We’d like to understand how they affect the brain” and perhaps even identify genes that might protect the brain against stress and disease.

Genetically encoded, nature-inspired transparency in the mammalian brain

Finally, in perhaps the most “future is now” project of the bunch, scientists are working to make live mouse brains transparent.

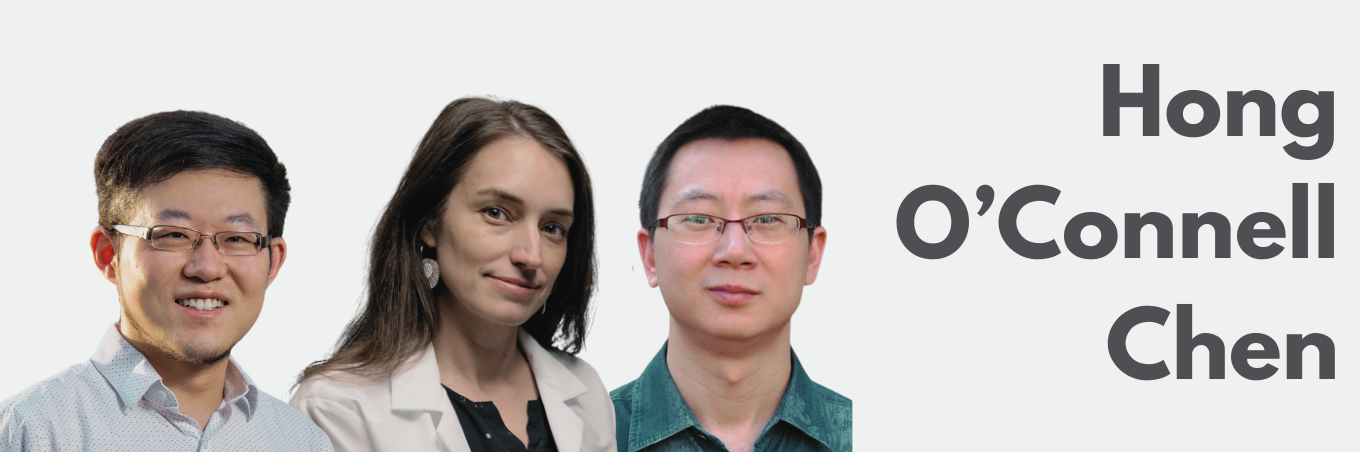

To do so, materials scientist Guosong Hong, a Wu Tsai Neuro Faculty Scholar, is teaming up with biologists Xiaoke Chen and Lauren O’Connell of the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences to develop genetic tools to turn what sounds like science fiction into reality.

“There are lots of applications that use light to study the brain, including calcium and voltage imaging and optogenetics tools,” said Hong, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford Engineering, “but light can’t penetrate deeply enough into the tissues.”

As a result, researchers currently rely on invasive methods that cause both acute and long-term tissue damage to animals. “Our long-term goal is to obtain a four-dimensional map of brain activity—with the first three dimensions representing space and the fourth representing time—at optical resolution without the need for invasive approaches,” Hong said.

Doing so will require O’Connell’s knowledge of naturally see-through glass frogs, Chen’s experience building molecular toolkits to genetically engineer the brain, and Hong’s engineering skills and familiarity with turning skin and muscles transparent in live animals.

The sum is greater than the parts

None of those projects would be possible, the researchers said, without the Big Ideas program encouraging researchers to take on ambitious problems and work across schools and departments to solve them.

“None of us could do this alone, but maybe together we can figure something out,” said Svensson, of the neuro-pregnancy project.

Thaiss, part of the sickness and fatigue project, echoed that perspective. “Julia has developed many techniques for studying the gut nervous system, Luis has been studying the brain circuitry of sleep for a long time, and my lab has been developing tools for studying sensory neurons in the gut,” Thaiss said. “Each of those would be interesting standalone projects, but now we’re trying to integrate everything. The advantage is that we can find connections between these different points that would otherwise be hard to find.”

Without Big Ideas, the effort to make transparent brains—and the science that could come out of that—might not have gotten off the ground, said Chen, an associate professor of biology at Stanford Humanities and Sciences. “We were always talking about finding an opportunity to work together, and that’s why this kind of internal funding mechanism is so critical. It gives us a way to pursue some crazy ideas that might have a major impact.”

Big Ideas 2026

The Stanford Neuro-Pregnancy Initiative

Nirao Shah, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and of Neurobiology (School of Medicine)

Katrin Svensson, Associate Professor of Pathology (School of Medicine)

Longzhi Tan, Assistant Professor of Neurobiology (School of Medicine)

Pregnancy is an incredible journey in which the mother’s body and brain go through profound changes to support her and her growing baby. But we do not understand how the mother’s brain manages these changes or even how pregnancy affects memories, thinking, and emotions. This huge knowledge gap makes it challenging to treat conditions like pregnancy-related anxiety or depression that affect tens of millions of women globally every year. Our project is the first effort of its kind to understand how the brain adapts to and supports pregnancy. Our foundational studies will be done in mice but we will use state-of-the-art technologies, including AI, to quickly pivot to studies that directly advance understanding of human pregnancies. We will develop and use cutting-edge tools to define and understand how pregnancy hormones guide brain cells to adapt and support pregnancy. In pilot studies in mice, we have already discovered brain cells that respond to estrogen and are crucial for a healthy pregnancy. In parallel, we will build the first-ever collection of biomarkers of pregnancy, a collection that we will expand with newer technologies. We are confident that these biomarkers will become a critical toolkit globally, both to study basic aspects of pregnancy in the lab and to provide the best possible pregnancy care in the clinic. We believe our project will revolutionize our basic understanding of pregnancy. By unlocking the secrets of the dialog between pregnancy hormones and the brain, our project will also lead to healthier mothers and babies.

A New Precision Neuroscience of Language

Laura Gwilliams, Assistant Professor of Psychology (School of Humanities and Sciences)

Jaimie Henderson, Professor of Neurosurgery (School of Medicine)

Cory Shain, Assistant Professor of Linguistics (School of Humanities and Sciences)

Frank Willett, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery (School of Medicine)

Despite centuries of research and an urgent clinical need, language remains far less understood than motor and sensory systems in the brain. This gap stems from two key challenges: (1) a lack of recording techniques that can capture all relevant spatial and temporal scales at once, resulting in independent silos of scientific inquiry constructed around particular techniques, and (2) substantial individual variation in the functional brain anatomy underlying language and other higher-order cognitive abilities. To address these challenges, we propose a new precision neuroscience approach to language that aims to build individual profiles of each person’s unique cortical representation of language, using multiple recording methods (from whole-brain imaging to single neuron recordings). For the first time, this will enable critical tests of theories formed at one scale with data from another. Specifically, we will investigate how macroscale networks identified by fMRI (e.g., the "language network") relate to microscale neural tuning properties, and how the neural representations of language evolve over time at different scales. Finally, we will leverage this precision neuroscience approach to help build neuroprostheses that seek to restore language. We will create personalized implant targeting methods to identify regions containing neural representations most useful for decoding, removing a key outstanding barrier to clinical translation. A precision neuroscience of language will center the individual over group-averaged models, offering the potential for transformative insights into language representation and a paradigm shift in how we study the neural basis of human cognitive functions.

In Vivo Functional Genomics and Foundational Virtual Models of Brain Homeostasis and Resilience*

Thomas Clandinin, Professor of Neurobiology (School of Medicine)

Will Allen, Assistant Professor of Developmental Biology (School of Medicine)

Xiaojie Qiu, Assistant Professor of Genetics (School of Medicine)

*Co-sponsored by the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience

The brain exhibits remarkable resilience to stress and damage, yet with advancing age, cognitive function often declines, and the risk of neurodegenerative disease rises. How do neurons and glia respond to stress and damage, and how does this ability change with age? In spite of decades of work, our mechanistic understanding of brain resilience has been fundamentally limited by the absence of the tools needed to dissect the functions of resilience processes that engage thousands of genes across many cell types, over a lifetime. To overcome this barrier, this project will build new tools for probing gene function and will use these tools to systematically unravel how the brain responds to stress at a molecular level. These data will then be used to train an AI network that will interpret how these genetic networks function to make predictions about specific pathways that control brain resilience. These predictions will then be tested in animals, setting the stage for targeted manipulations and extension to humans.

Genetically encoded, nature-inspired transparency in the mammalian brain

Guosong Hong, Assistant Professor of Materials Science and Engineering (School of Engineering)

Lauren O'Connell, Associate Professor of Biology (School of Humanities and Sciences)

Xiaoke Chen, Associate Professor of Biology (School of Humanities and Sciences)

Imagine if we could watch the brain in action – deep inside – without surgery or implants. That bold vision drives our Big Ideas in Neuroscience project. Inspired by animals like glass frogs, whose organs are naturally see-through, we are developing a new kind of laboratory mouse with a transparent brain.

This transformative approach combines cutting-edge physics and biology to eliminate the intrinsic opacity of brain tissue in live mammals. In most mammals, such as rodents and humans, the brain scatters light, making it difficult to see what lies beneath the surface. In contrast, glass frogs produce special proteins that match the optical properties of their tissues, allowing light to pass through with minimal distortion. We aim to replicate this level of transparency in the mammalian brain by introducing proteins with similar optical properties using safe genetic techniques.

The ability to achieve transparency in the brain holds significance for neuroscience, as many of the brain’s important control centers – including those for hunger, thirst, stress, emotion, memory, and social behavior – are buried deep beneath the surface. Our approach would enable scientists to observe and influence these circuits in real time, in awake, behaving animals, without the need for invasive procedures.

This research has the potential to fundamentally change how we study the brain and treat neurological diseases. It paves the way for safer, more precise therapies and a deeper understanding of how the brain drives behavior. Much like the discovery of fluorescent proteins revolutionized biology, transparent brains could transform the future of neuroscience.

Immunomodulation of gut-brain interactions

Julia Kaltschmidt, Associate Professor of Neurosurgery (School of Medicine)

Luis de Lecea, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences (School of Medicine)

Christoph Thaiss, Assistant Professor of Pathology (School of Medicine), Core Investigator (Arc Institute)

How does the brain interpret signals from the body, and how do peripheral systems respond to brain signals? A fundamental function of central nervous systems in all animals is their ability to sense and integrate information from the environment. Equally important but much less understood is the brain’s ability to perceive information from inside the body. We propose to study the bidirectional interaction between body and brain from the perspective of the immune system. This interplay is particularly relevant in the context of sickness behavior. Immune responses to infections in the body affect the brain and result in increased sleep and fatigue. Conversely, neuronal circuits in the brain send signals to peripheral organs and orchestrate immune responses. However, many aspects of these interactions remain mysterious, and fatigue associated with chronic infections or post-infection syndromes, such as Long COVID, is a major health concern. We propose to study body-brain communication with a particular focus on gastrointestinal infection. We will (i) determine how peripheral infection triggers signals from the gut that affect sleep behavior; (ii) study how neuronal gut-brain signals influence brain states regulating arousal and fatigue; and (iii) interrogate neuronal pathways emanating from brain structures that modulate immune responses to infection in the gut. Collectively, these aims will enhance our understanding of neuroimmune connections and will serve as a blueprint for the systematic interrogation of body-brain circuits through interactions between groups at Wu Tsai and the broader Stanford community.