Non-invasive brain stimulation opens new ways to study and treat the brain

The control panel to the human experience is hidden inside a bony box.

We can thank our skulls for keeping our brains safe. But this protective case also makes the three-pound organ that generates our mental lives and behavior particularly challenging to study and treat. Add to this the sheer complexity of the human brain—100 billion neurons, with more than 100 trillion connections among them. It is perhaps not surprising that even today, much remains enigmatic for neuroscientists.

Scientists have been probing the brain with electrodes for nearly a century. As early as the 1930s, researchers such as Wilder Penfield mapped the function of brain tissue concerning the sources of seizures by opening windows into the skulls of epilepsy patients and applying current directly to their brains. These studies helped Penfield and others cut out the sources of seizures while minimizing functional damage—and also provided scientists with some of the earliest clues to the function of various brain areas. Today, techniques like deep brain stimulation (DBS) use long-term electrode implants to alter brain activity and improve outcomes for people with Parkinson’s, epilepsy, and other neurological disorders.

But most studies and treatments using brain stimulation still involve physically penetrating the skull in some way, and implanting electrodes in the brain. Chips and wires require surgery to be properly placed, and often need to remain long-term. Such challenges have limited the widespread use of potentially transformative therapies.

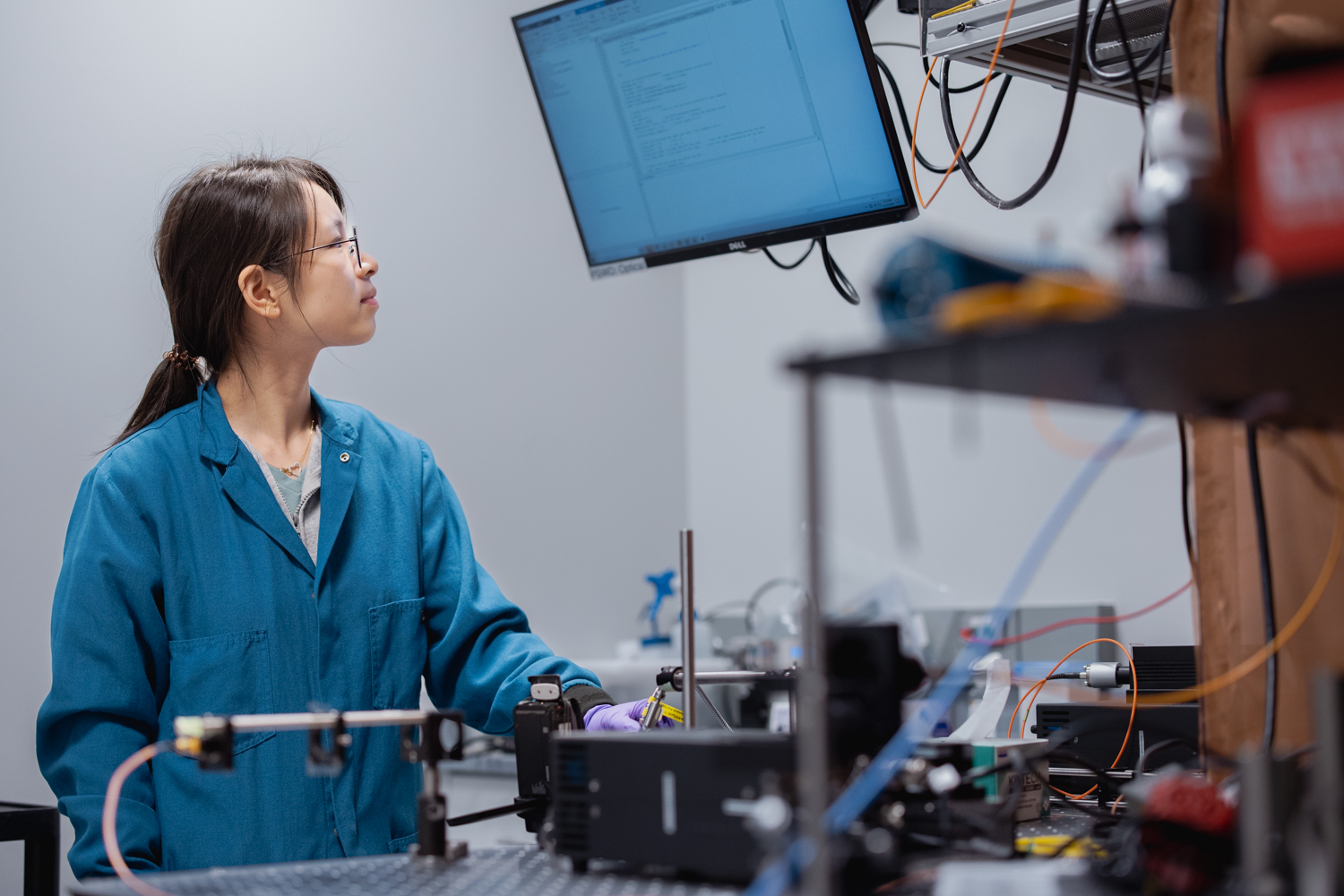

Now, a new generation of researchers at Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute is exploring ways to understand and treat the brain using less invasive approaches—without implanting anything or drilling into the skull.

Magnetic modulation

Some non-invasive approaches are already being used clinically, and Wu Tsai Neuro researchers are working to expand their impact.

For instance, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, is already transforming the lives of some patients with severe, treatment-resistant depression, offering relief from debilitating symptoms that have not responded to medication. Recently, psychiatry professor Nolan Williams and colleagues at Stanford Medicine developed the Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy (SAINT), an enhanced TMS protocol that produced remission in nearly 80% of patients with treatment-resistant depression. TMS has also recently been approved for obsessive-compulsive disorder and migraines.

Still, many questions remain about how and why TMS works, says Corey Keller, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medicine. TMS sends magnetic pulses into the brain, causing synchronized bursts of neural activity. The approved treatment protocol uses a specific pattern of pulses, but not everyone responds to it. Keller thinks that some patients—or some conditions—might respond better to a different pulse pattern.

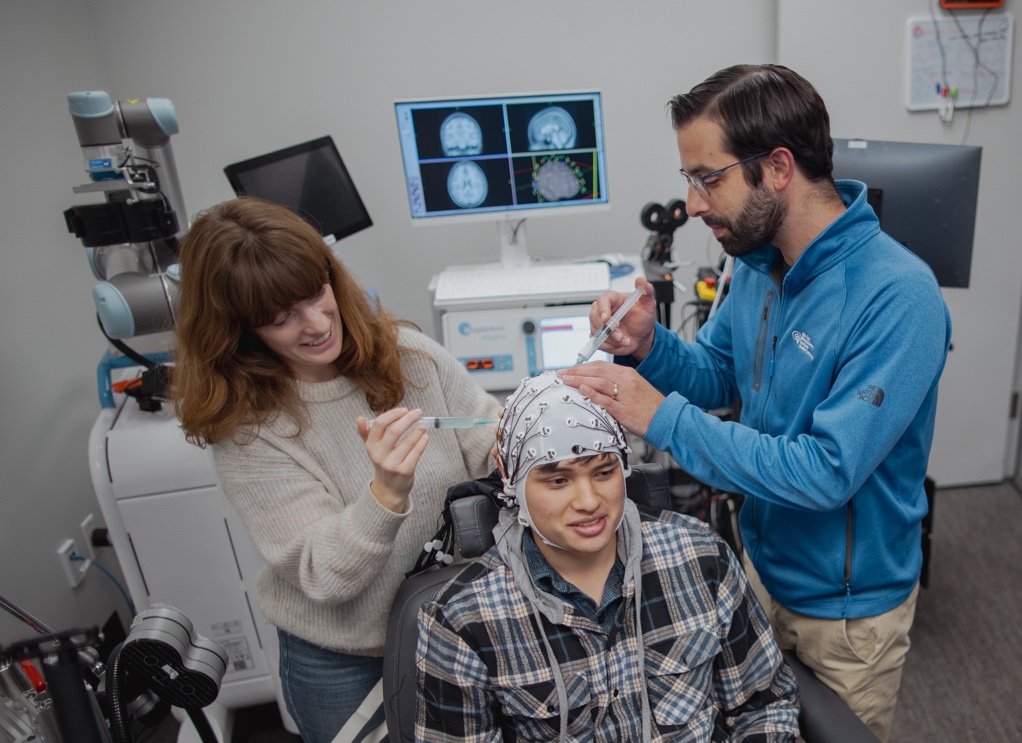

To understand how TMS magnetic pulses are altering neural activity, Keller’s lab is pairing it with a much older tool—the electroencephalogram (EEG). EEG measures electrical activity in the brain with accuracy down to the millisecond, via a network of electrodes placed on the surface of the patient’s scalp.

By matching EEG signals to TMS stimulation patterns under different conditions, Keller’s team gets a direct window into how TMS treatment is altering brain activity and can link those shifts to changes in symptoms.

“I want to be able to understand how our current treatments change the brain, and how these markers can be used as a clinical decision-making tool,” Keller says. “I feel we can help everyone once we know what their physiology looks like.”

Fiona Baumer, an assistant professor of neurology at Stanford Medicine, is using a similar approach to study and treat children with epilepsy.

At least half of kids with epilepsy also have cognitive issues, Baumer says. Children can have excessive bursts of electrical activity in their brains, called spike waves, even when they are not having a seizure. Children with frequent spike waves often have worse cognitive problems, and Baumer wants to understand why. Baumer’s lab has also used EEG to study brain function and has found that brain connectivity—a measurement of how different brain regions communicate with one another—is elevated in children with frequent spikes.

She wants to better understand whether these cognitive issues and extra connectivity are linked: Does being “hyper-connected” negatively affect cognitive performance, or does it reflect a brain compensating in some way for the effects of epilepsy?

“When you have a neurologic disorder, your brain can behave differently than that of someone without the disorder. Sometimes these differences cause bothersome symptoms and sometimes they reflect ways the brain has adapted to deal with the disorder and actually improve function,” Baumer says. “One of the biggest things I’m focused on is understanding what signals are actually pathological and are worsening cognition.”

Current ways of suppressing spike waves, like prescription benzodiazepines and steroids, come with a lot of side effects. Baumer’s team has seen short-term benefits from TMS treatments in the lab, lasting about as long as the treatment itself. Now, they’re testing ways to make those benefits longer lasting. They have found that when spikes are reduced by TMS, connectivity also decreases, suggesting that the spikes may be causing that hyperconnectivity.

Like Keller, Baumer is also utilizing EEG to better understand how TMS is shifting the brain from baseline, and to measure whether treatments are working.

“One of the challenges of studying cognition is that it’s hard to do in other species. While we have so many beautiful animal models for many things, models of cognition and language don’t translate as closely,” Baumer says. “We have to be pretty humble in that we don’t fully understand how epilepsy is interacting in the brain. Non-invasive methods for studying these questions—and treating some of these problems—will be a game changer, particularly for children.”

We interviewed Kaestner about the then-new Koret Human Neurosciences Community Laboratory in 2023. Read the Q&A

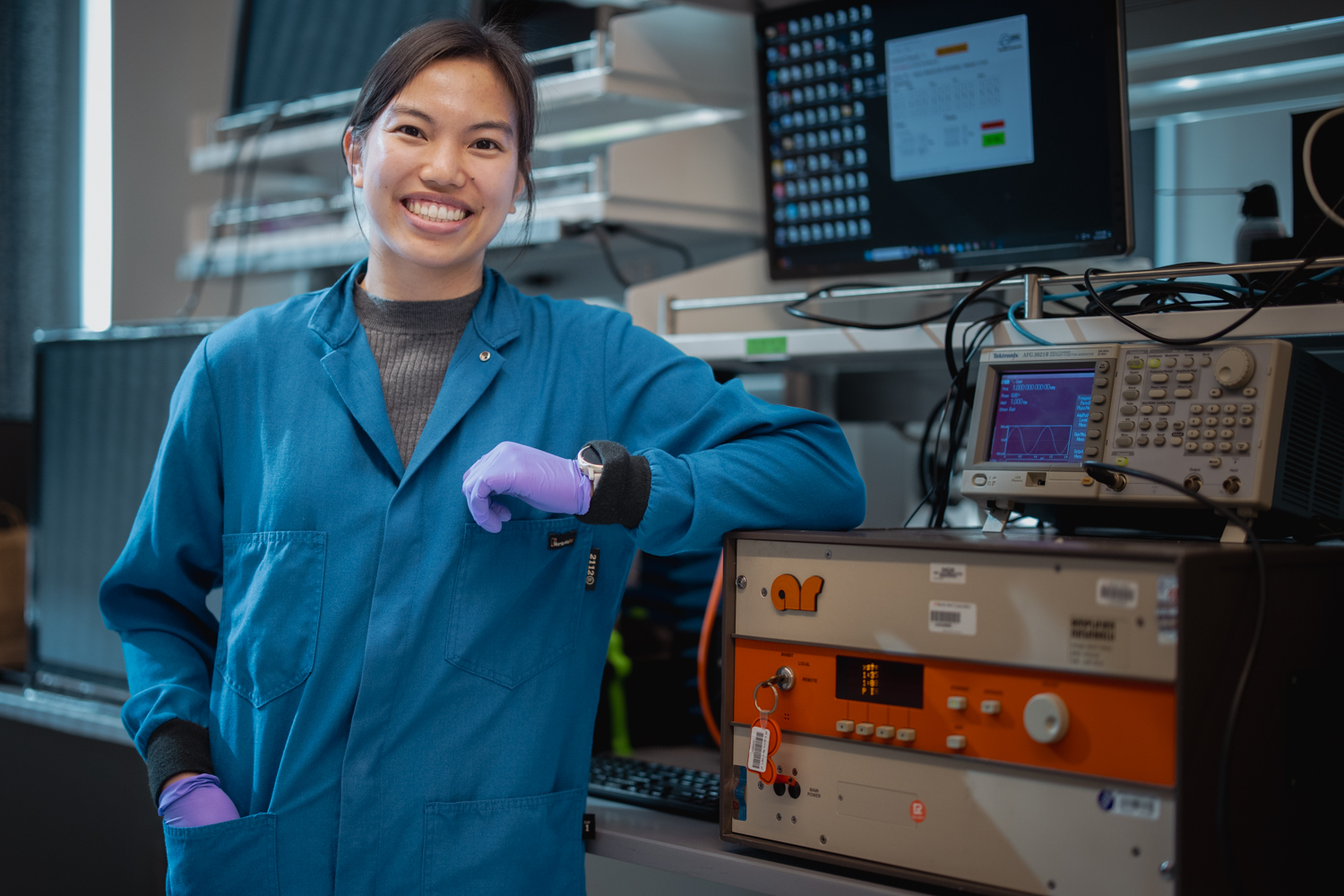

Both Keller and Baumer are taking advantage of a shared resource that makes exploring the brain non-invasively more accessible. The Koret Human Neurosciences Community Laboratory at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute gives researchers across the Stanford community access to both TMS and EEG instruments, bringing together people from across campus and offering support, expertise, and training around tools that would be prohibitively expensive for individual labs.

“It’s really about fostering those cross-campus collaborations, and also allowing people to push the envelope of their research in a new direction,” says center director Milena Kaestner. “In terms of innovation and novel research, having a center like this creates a way to lower the bar to entry. And I think that’s pretty special.”

Ultrasound, focused

Another non-invasive brain stimulation technique harnesses sound waves to go much deeper into the brain than TMS can, targeting specific spots with great precision.

Ultrasound is perhaps best associated with safely monitoring babies in utero, but when its beams are focused down to a point the size of a grain of rice, they can concentrate enough energy to zap faulty brain wiring to relieve symptoms of epilepsy or tremors. At much lower intensities, focused ultrasound beams could be a way to tweak neural activity safely—with no electrodes needed.

Kim Butts Pauly, a professor of radiology at Stanford Medicine, is investigating the potential of low-intensity, focused ultrasound (at levels similar to what’s currently used for clinical imaging in obstetrics and orthopedics) to directly alter neural activity.

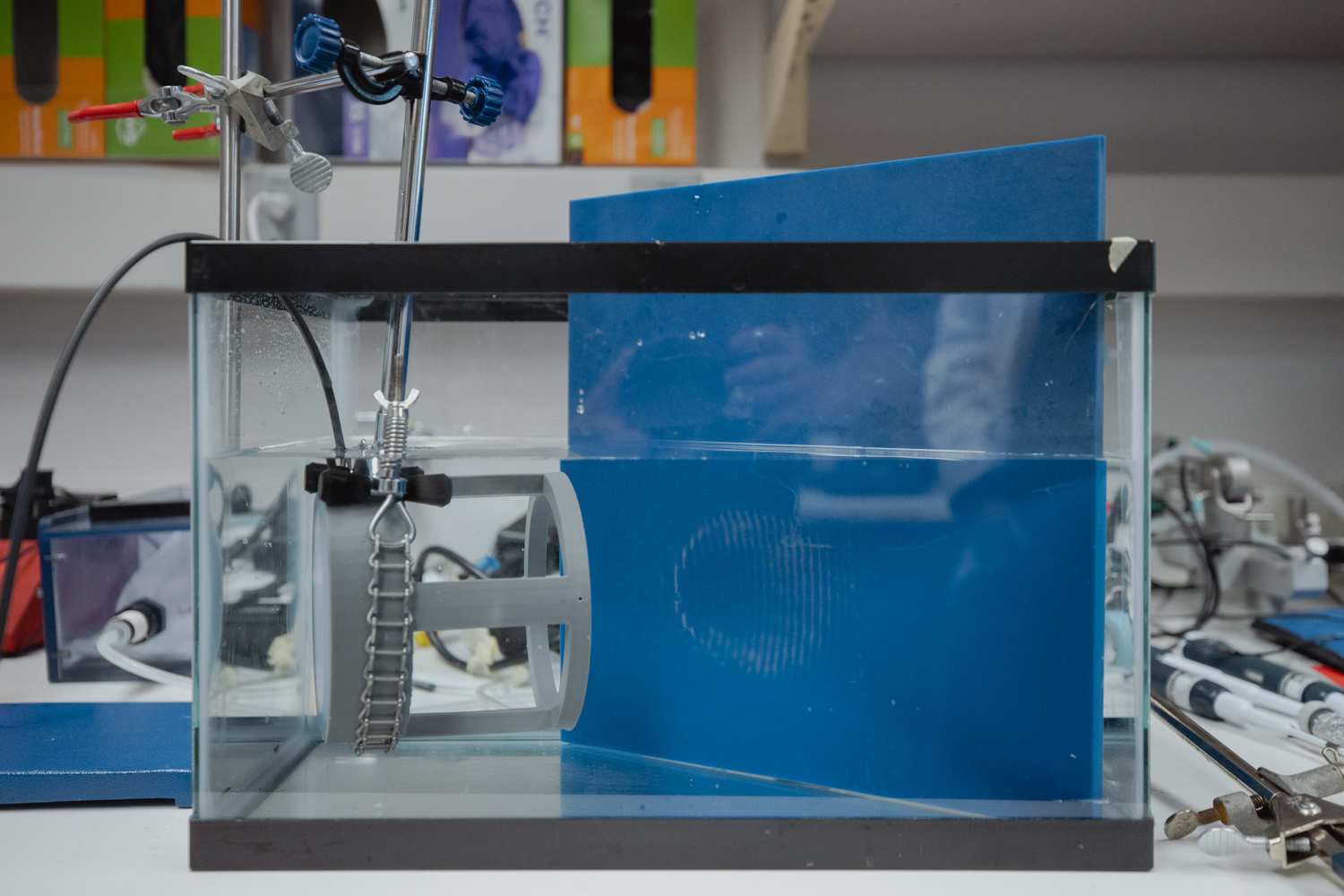

This approach is literally inching its way toward clinical use, with potential application for epilepsy, Parkinson’s, and many other conditions. Butts Pauly’s team is probing the basic physics of how ultrasound is interacting with the brain—the way the sound waves interact with the membranes of neurons to cause signaling to shift, for instance. They’re trying to solve problems that need to be addressed before focused ultrasound can be more widely adopted clinically. For instance, ultrasound waves get distorted when they travel through the skull; the lab is developing simulations that predict how this journey will alter the path of an ultrasound wave, so that the treatment can be calibrated to hit the desired spot.

“We’re working on developing the tools for translation and understanding what we’re doing in animal models,” Butts Pauly says, with the hope of moving the treatment into broader clinical use.

Ultrasound can also be used alongside other technologies to affect brain activity indirectly, such as by carefully targeting drug delivery.

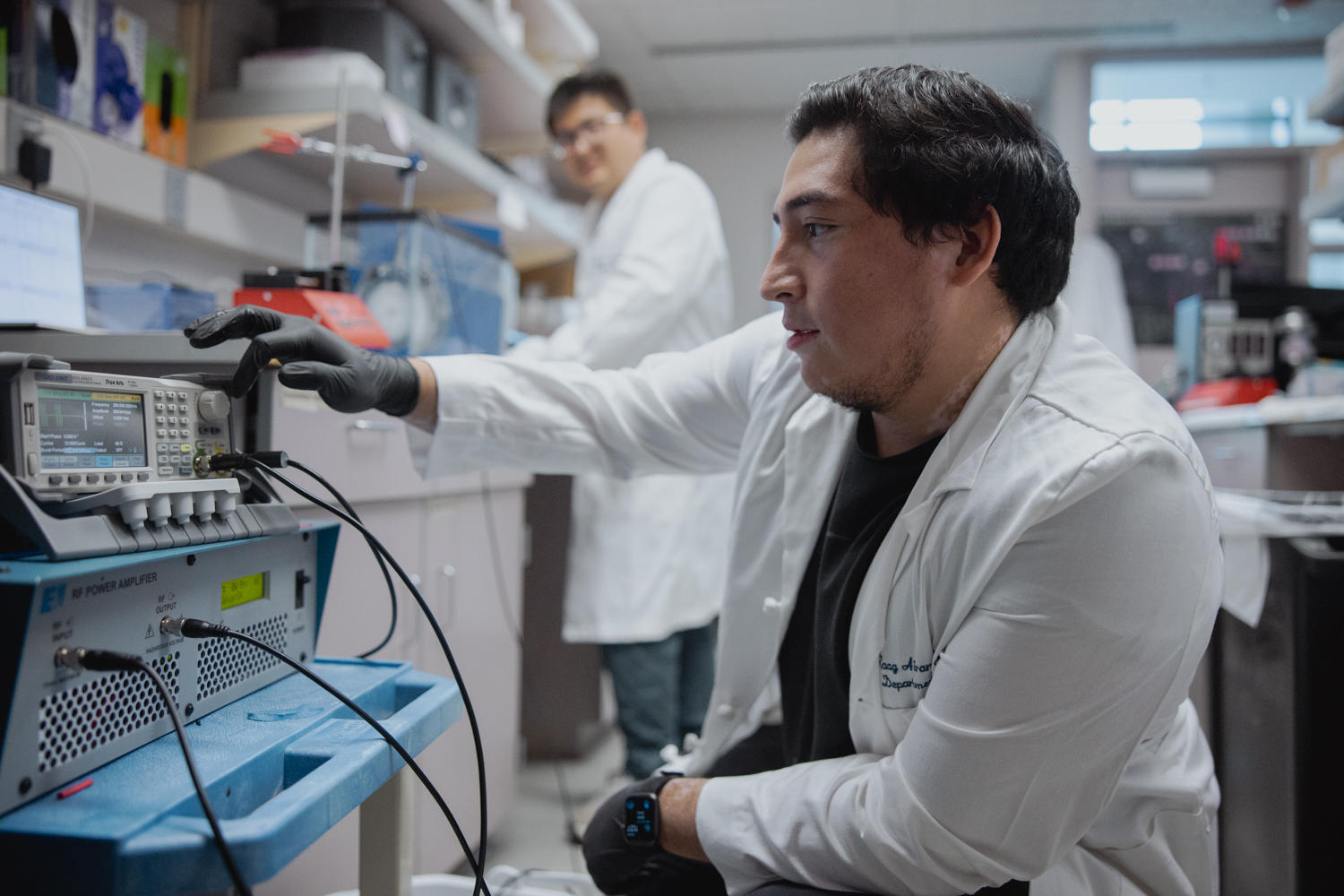

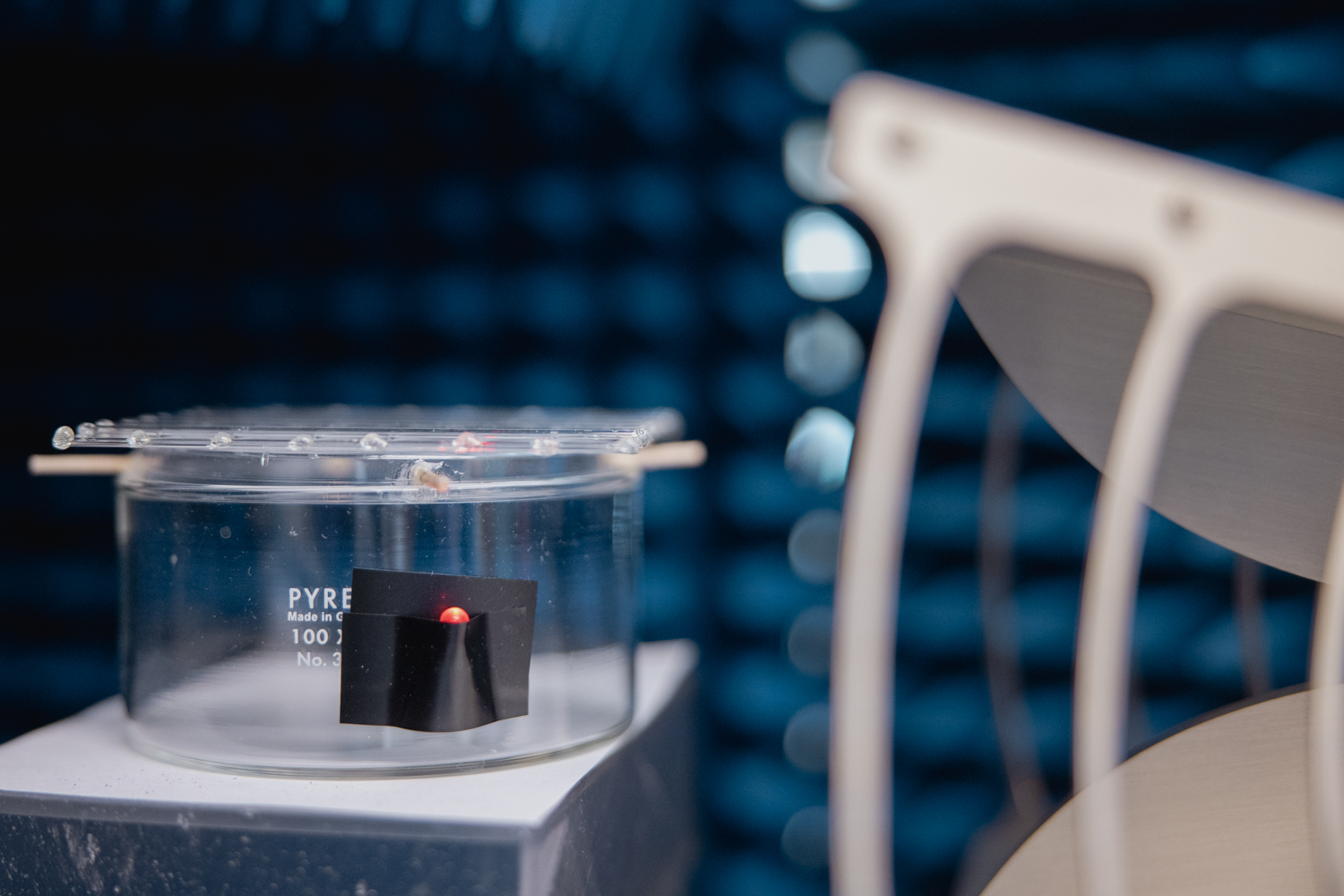

Raag Airan, an assistant professor of radiology, is blending focused ultrasound with nanotechnology to get drugs to hit precisely when and where they are needed. Medication that affects brain function can help people with a wide range of conditions, from depression to chronic pain to Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. But these drugs often have off-target side effects as they circulate throughout the whole body.

“We asked: How can we pair the power of ultrasound to target different parts of the brain at will with the potent effects of pharmacology?” Airan says.

Airan envisions drugs that are shrouded in nanoparticle shells—like the candy coating on an M&M. Patients could receive an intravenous infusion of these drugs, which would spread in the blood while inert until they enter a beam of focused ultrasound waves targeted to a specific spot in the brain. Then, the ultrasound beam would allow the drug to leak through the nanoparticle shells, allowing the freed drug to enter the brain when and where it’s needed most.

While the technique has the potential for wide applicability, Airan’s team is focused on pursuing clinical trials for using ultrasound-sensitive anesthesia drugs and ultrasound-sensitive ketamine for acute and chronic pain, substance use disorder, and epilepsy.

Ultrasound-sensitive anesthesia drugs could be used to selectively numb a particular part of the brain to see if deactivating that area improves symptoms—i.e., a reversible test-run before going all-in on a non-reversible procedure.

Ketamine, meanwhile, is an anesthetic that has gained traction recently as a way to treat depression and chronic pain. Targeting ketamine to specific brain areas could be a way to ease chronic pain with fewer side effects and less risk of addiction compared to alternatives like opioids.

This nano-powered approach is still a few years out from broad application, Airan predicts, but the research—which got its start with a 2019 seed grant from Wu Tsai neuro—has recently been funded for clinical trials with ketamine and other anesthesia drugs. (Airan has also received funding from the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Wu Tsai Neuro to use ultrasound to enhance waste clearance from the brain.)

A flashlight for the brain

Other Wu Tsai Neuro scientists are using materials science and engineering to riff on tools that have transformed neuroscience research in lab animals, but haven’t yet been practical candidates for human translation.

Take optogenetics, for example: In the early 2000s, Stanford bioengineer Karl Deisseroth led the development of this powerful way of using light to precisely manipulate brain circuits in lab animals, in which an implanted light source selectively activates neurons that have been genetically modified to be light sensitive.

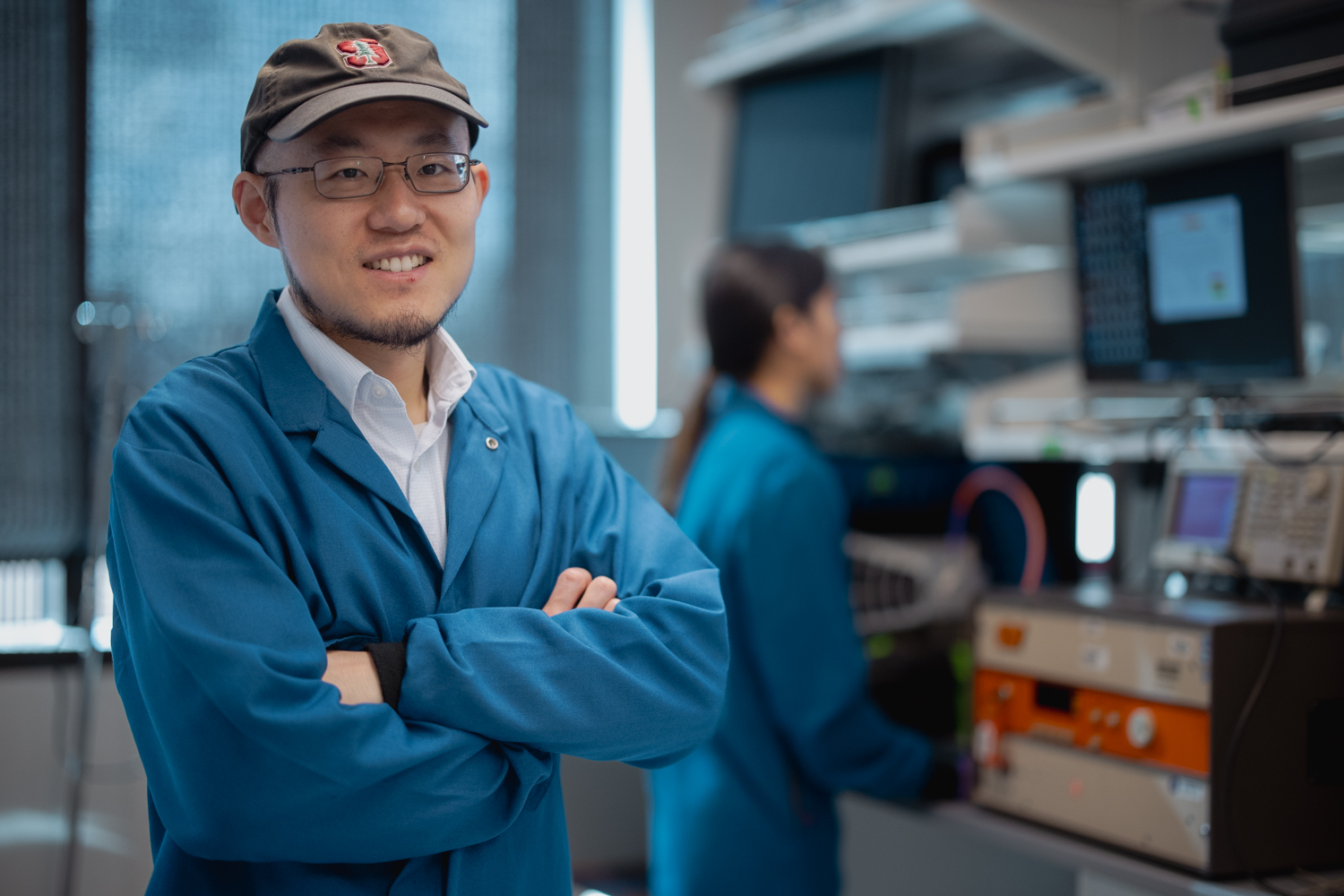

Now, Guosong Hong, a Wu Tsai Neuro faculty scholar hired by the institute into the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, is working on non-invasive ways to use light and other energy sources to manipulate neurons. (His team recently made headlines for discovering that common food dye could render the skin of living animals transparent.)

Hong—whom the MIT Technology Review named in its prestigious list of 35 Innovators Under 35 in 2020— and his team have engineered specialized molecules and nanomaterials that can convert mechanical energy into light. When activated by ultrasound waves, these materials light up—much like bioluminescent algae in the ocean that glow when stirred up.

“This provides a nice way to address a previously invasive challenge,” Hong says. The approach could be used to image deep parts of the brain, or—paired with the right technology—to activate specific neurons. And unlike approaches that require an implanted light source, the ultrasound beam could be rapidly refocused to different regions in precisely timed patterns, like a flashlight in the brain.

Another approach under development in Hong’s lab takes advantage of the fact that infrared light penetrates the body more readily than visible light. In recent studies, they’ve delivered infrared-sensitive ion channels—the basis for neurons’ electrical activity—to the brain via a harmless virus. Then, when focused infrared light hits the relevant brain region, those neurons activate. It’s a potential way to turn on certain neural circuits from a distance, with no drilling into the skull necessary.

Right now, these approaches are still being tested in rodents. But because they’re less invasive than their predecessors and don’t involve implanting anything, they have greater potential for eventual human translation, Hong says.

“We’re currently doing it in mouse models, but what really excites us is it has the potential to translate a lot of the optical stimulation methods developed by other groups over decades to human clinical studies.”

Hong’s work might sound like science fiction. But he and other Wu Tsai Neuro researchers all share a clear, attainable vision for the future—one where the brain can be more easily studied and treated while keeping the skull intact. If successful, it holds the promise of facilitating basic research, making it easier for scientists to study the workings of the brain in model organisms. And it will transform medicine, making treatment of complex brain conditions safer, easier, and more accessible.

Wu Tsai Neuro makes this possible by breaking down silos between scientists working on similar problems from different angles, Airan says. “Wu Tsai Neuro helps pull all of us together in community.”