How to rewire a fruit fly brain

How your brain gets wired up matters. Consider the neurons involved in your sense of smell. Hook them up wrong, and suddenly turpentine might smell like a lovely chianti. At best, following your nose could lead you into danger or at least some puzzling behavior.

Yet how our developing brains get the wiring right and keep us out of trouble remains unclear. Without that knowledge, it’s hard to understand how the brain forms the circuits that drive behavior.

Now, Wu Tsai Neuro scientists have taken major steps toward a deeper understanding of the brain’s wiring system. In two papers published November 19, 2025, in the journal Nature, researchers in the lab of neurobiologist Liqun Luo—the Ann and Bill Swindells Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences and a professor of biology—first probed the forces underlying neuron wiring in brain regions responsible for fruit flies’ sense of smell. Then, they showed they could rewire those systems to change flies’ behavior.

“As Richard Feynman said, ‘What I cannot create, I do not understand,’” said postdoctoral fellow Cheng Lyu, who led the work with graduate student Zhuoran Li. “Now that we’ve done this, we are one step closer to understanding the whole system.”

An old puzzle

Neuroscientists have figured out a lot about how neurons form synaptic links to build functional neural circuits, and new discoveries keep coming.

But how neurons find the correct partners to link up with in the first place—sometimes over impressive distances—has been a bit harder to figure out.

It’s a complicated task. Even in the brain of a tiny insect, each region contains thousands of neurons in dozens of varieties. If neurons don’t match up in sensible ways, circuits may not form as expected—and the brain might not work as expected either.

In the fruit fly olfactory circuit, for example, there are about 50 different types of neurons that receive smell signals from the antennae, and another 50 or so types that send those signals into the brain. If those don’t get paired up in the usual way, a fruit fly might go in search of wet concrete when it should instead hunt down some tasty bananas to chew on.

(Why fruit flies, you may ask? Because they have relatively simple brains compared to, say, mice or humans, and because there are abundant genetic tools for researchers to distinguish individual types of neurons and to alter gene expression, it’s much easier to see what’s going on inside the fly brain.)

More than six decades ago, neurobiologist Roger Sperry proposed a solution to the puzzle: Neurons might come with chemical tags—molecules that are expressed on the surface of cells— that would help one another sniff out their matches.

That hypothesis turns out to be largely correct, albeit incomplete. There are so many neurons in the brain that the relatively small number of chemical tags researchers have discovered aren’t enough to solve the matching problem.

Earlier this year, Luo, Lyu, Li, and other members of Luo’s lab found one way neurons simplify the problem. To sniff out potential partners, neurons extend their axons, the long branches that send signals to downstream neurons. Writing May 1 in Science, the Luo lab showed that those axons follow predetermined paths rather than search an entire three-dimensional brain region.

That narrows the possibilities considerably, Luo said, but still doesn’t eliminate the problem, said Luo. Even with chemical tags and smaller search spaces, each neuron will still encounter a large handful of others it could match with.

A neuron’s gag reflex

In the first of the two new papers, Li and her lab-mates explored whether the nature of the chemical tags themselves might address the remaining issues.

Sperry’s original hypothesis, Li said, involved what are called “attractive” chemical tags. In that case, a neuron’s axon grows toward other neurons with matching tags.

But there’s another possibility: repulsion. Previous research has shown that both attraction and repulsion help determine the search paths axons take. There is evidence that repulsive chemical tags play a role in other wiring processes—for example, keeping a neuron from forming synapses with itself.

Whether repulsion played an important role in the final stages of synaptic partner matching was less clear, so Li set out to find some repulsive tags. Li and the lab focused on two kinds of olfactory neurons that sense different smells. Crucially, those two have the same attractive chemical tags, meaning that other neurons would not be able to distinguish them using attraction alone.

Drawing on a single-cell RNA sequencing database—built as part of the Neuro-Omics Initiative, a 2018 Wu Tsai Neuro Big Ideas project—Li and colleagues identified three genes that produce previously unknown chemical tags. When the team knocked out those genes, brain circuits ended up cross-wired: Axons that ordinarily linked only to one of the two neuron types ended up wired to both. That suggests that the new tags repelled certain kinds of neurons, Li said.

Creating is understanding

To check whether the group really understood the role of attraction and repulsion in synaptic partner matching, however, the team decided they needed to show they could use their knowledge to control how olfactory circuits in the fruit fly brain formed.

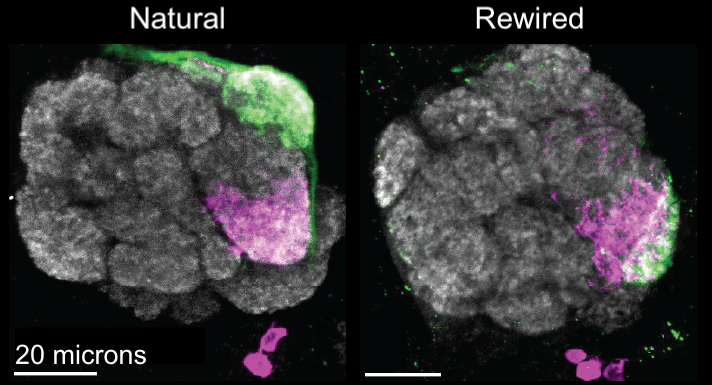

In the second Nature paper, Lyu and the team did exactly that. By changing how much different genes were expressed, they manipulated a specific type of olfactory receptor neuron in three ways: increasing repulsion between usual neuron partners, decreasing repulsion between new partners, and increasing attraction between new partners.

Lyu and colleagues demonstrated that these changes physically rewired fruit flies’ brain circuits, and also that this rewiring changed flies’ behavior. Ordinarily, the receptor neuron the team studied plays a role in mating behavior—in particular, it discourages male flies from trying to mate with other males.

Rewired male flies, however, attempted to court both male and female partners. Male flies chased other males, vibrated their wings to produce courtship songs, and showed other signs of attempted mating.

Still more to learn

The results are significant steps toward figuring out how brain circuits form, Luo said: Having shown it’s possible to control which neurons will link up with each other and subsequent behavior means that they know in detail how neurons form the links that underlie brain circuits.

At least they know how that works in the fruit fly olfactory system. Now, they need to study how other types of neurons wire up elsewhere in the fly olfactory system and throughout the fly brain. The team is also curious to see how the wiring principles they’ve discovered play out in other animals, such as mice.

“This is an important milestone in one part of one circuit,” Luo said of the new paper. “Now, the question is, ‘Does this generalize?’”

Publication Details

Repulsions instruct synaptic partner matching in an olfactory circuit

Research Team

Study authors were Zhuoran Li, Cheng Lyu, Chuanyun Xu, Ying Hu, David J. Luginbuhl, and Liqun Luo from the Department of Biology in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and Asaf B. Caspi-Lebovic, Jessica M. Priest, Engin Özkan from the University of Chicago.

Research Support

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-DC005982 and R01-NS139060, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the Gatsby Foundation, and the Stanford Science Fellows Program. Luo is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rewiring an olfactory circuit by altering cell-surface combinatorial code

Research Team

Study authors were Cheng Lyu, Zhuoran Li, Chuanyun Xu, Jordan Kalai and Liqun Luo from the Department of Biology in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Research Support

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-DC005982), the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the Gatsby Foundation, and the Stanford Science Fellows program. Luo is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.