Molecular toolmakers share glimpses of the future of brain science

Is there a genetic basis for polyamory? What is the molecular basis of memory? Will AI-modeled cells lead to a boom in virtual neurobiology? Neuroscientists and enthusiasts recently packed every seat and lined the walls of a conference room in the James H. Clark Center to find out.

The symposium, held May 2, 2024, was organized by the Neuro-omics Initiative, an interdisciplinary research consortium — launched in 2018 by the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute’s flagship Big Ideas in Neuroscience grant program — that aims to apply advances in gene sequencing (genomics), RNA sequencing (transcriptomics), and protein sequencing (proteomics) to advance neuroscientists’ understanding of the evolution, development, and function of the brain’s remarkably complex wiring.

Participating labs have already answered many stubborn neurobiological questions, and the still unpublished research they presented at the symposium promises even more significant breakthroughs. The symposium featured talks from seven neuroscientists on topics including gene expression and behavior, mRNA and its role in long-term memory, and the latest technologies for mapping cells.

“Our goal is to apply modern transcriptomic tools to basic neurobiology questions. It’s daunting work—very hard technically but very exciting,” said Neuro-omics co-director Liqun Luo, the Ann and Bill Swindells Professor in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, and a professor of biology. “I was happy to see the room filled to capacity with attendees from across the schools of medicine, engineering, and humanities and sciences.”

Early breakthroughs with RNA sequencing

The day kicked off with a keynote presentation by Joshua R. Sanes, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University. Sanes described a long-standing puzzle in visual neuroscience: Why do primates see with such greater acuity than mice, despite the fact that all vertebrate retinas are — seemingly — remarkably similar? Using advanced transcriptomic techniques, Sanes shared his team’s discovery that the retinal structure responsible for our high acuity vision does not result from the evolution of distinct cell types by our primate ancestors, as most researchers thought, but from expansion of a set of cell types we share with our rodent cousins — with subtle differences in gene expression.

Sanes’s presentation aptly introduced the underlying theme of the symposium: the critical role of technological developments in transcriptomics in the advancement of neuroscience. Bulk RNA sequencing techniques have long been used to study signatures of gene activity in the brain, but these approaches blend the many different cell types that make up neural tissue, muddying the resulting measurements. In the 2010s, new single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) techniques — which deconstruct tissue into its component cells and measure signatures of gene activity of individual cells by the thousands — began enabling scientists to identify rare cell types and genetic signals that would previously have blended into the background. Single-cell techniques have now allowed Sanes and his team to construct a comprehensive atlas of all the cell types in the mouse retina — what he calls the mouse retinome.

Gene expression and behavior

The next slate of presentations from Stanford Neuro-omics Initiative researchers were also all made possible by advances in transcriptomics.

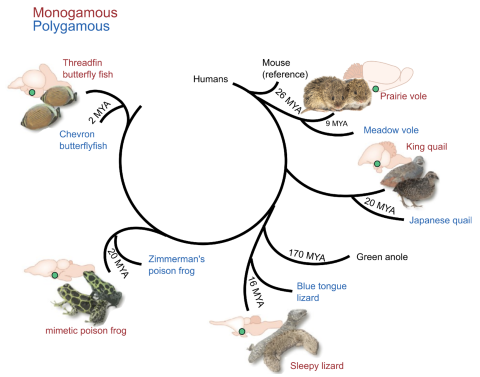

First up, Luo shared a previously published evolutionary study on how cell types in the cerebellum of simpler brains duplicated themselves to form the more complex human cerebellum. Luo then introduced still-unpublished research on the evolution of the hypothalamus—a structure located just above the brain stem which controls many metabolic processes like sleep, hunger, thirst, as well as social behaviors like mating and parenting, conducted jointly by Luo and fellow Neuro-omics researchers Bo Wang, Lauren O’Connell, and Stephen Quake. The researchers wanted to know how cell types in the hypothalamus that control these behavior have evolved across vertebrates, and if traits like monogamy and polygamy arose from different cell types or subtler patterns of gene expression within the hypothalamus in different classes of vertebrates: fish, frogs, lizards, quails, and voles.

Yunming Wu, a postdoc in Luo’s lab, and Prateek Kalakuntla, a graduate student in the lab of Bo Wang in the Departments of Bioengineering and Developmental Biology, detailed these approaches and some of the early findings. They were able to match some of the hypothalamus cell types across vertebrate evolution. Furthermore, preliminary data from comparisons of monogamous and polygamous voles and quails suggest that specific RNA binding proteins may be expressed at higher levels in monogamous voles and quails compared to closely related polygamous species.

Completing the series on gene expression and behavior, graduate student Neil Khosla presented research from the lab of Neuro-omics Initiative member Lauren O’Connell in the Department of Biology, which demonstrated how changes in microRNA (non-coding RNA chains that influence protein transcription) can be changed by social factors. They measured how early-life isolation affected both brain microRNA levels and social behavior in poison frog tadpoles, with plans to evaluate the link between behavior and microRNA expression in upcoming studies.

RNA and memory

The topic of long-term memory was picked up by Neuro-omics co-director Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson professor of bioengineering in Stanford's Schools of Medicine and of Engineering and professor of applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences and Head of Science at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, who is a pioneer in single-cell and, more recently, spatial transcriptomic techniques.

The flip side of scRNA-seq’s ability to reveal gene signatures of individual cells is that it involves isolating cells from their context within the surrounding tissue. This not only makes it difficult to reconstruct where cells came from in the original tissue sample, but also eliminates potentially critical information about how neighboring cells of different types interact — usually involving specialized surface proteins. New spatial transcriptomics techniques — including approaches developed at Stanford by Quake, bioengineer Karl Deisseroth, and others — now allow cellular-resolution sequencing of slices of intact tissue — maintaining critical information about the genetic data’s anatomical and functional context. If single-cell RNA sequencing is a jigsaw puzzle, spatial transcriptomics provides the picture from the puzzle box to help guide assembly.

“Spatial transcriptomics helps you understand relative geometry, but it's not as good as scRNA-seq for things like gene discovery. So we use both, and they’ve come together in a really productive, interesting way. It's been a fun ride,” said Quake.

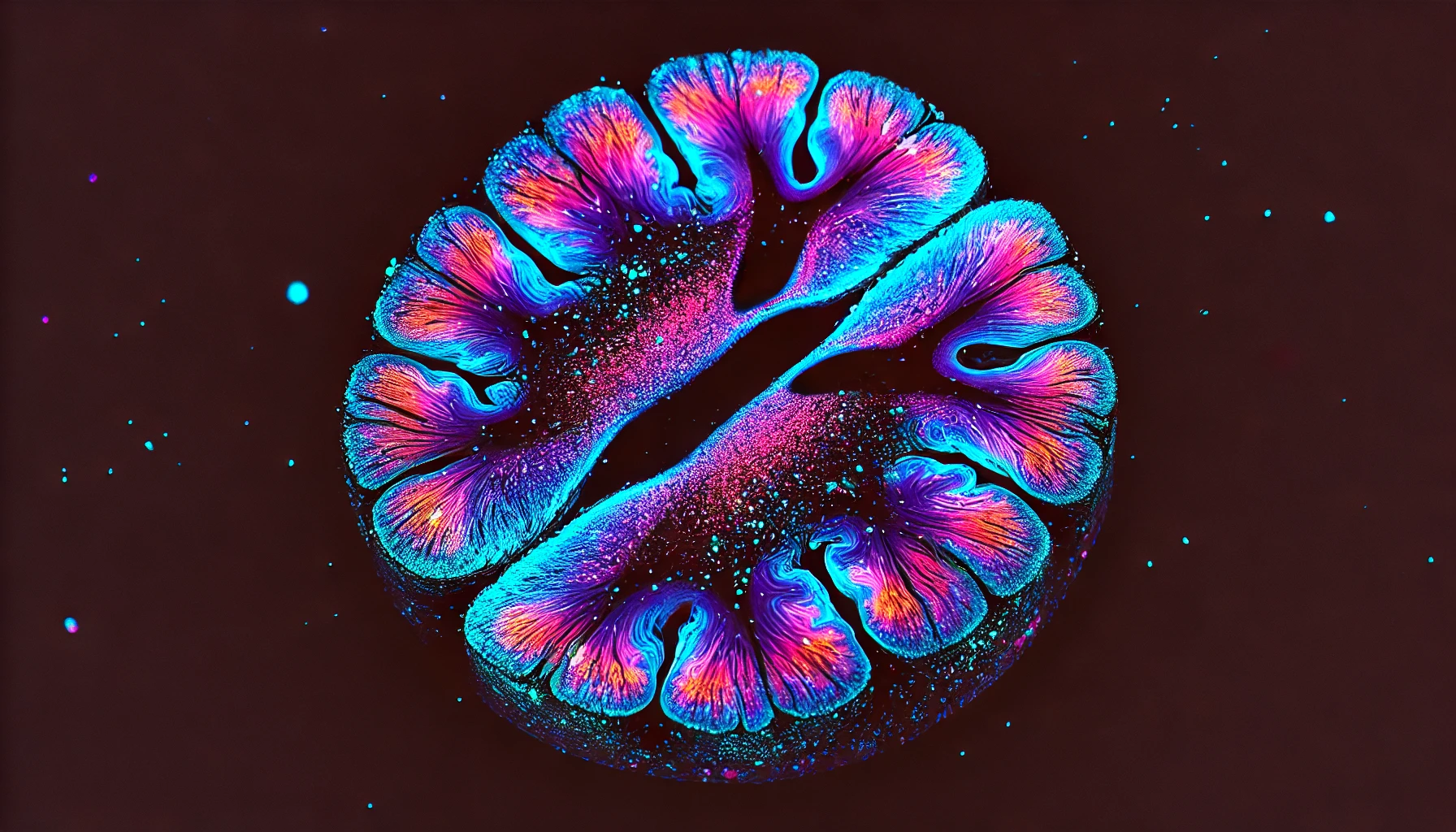

To audible gasps from the audience, Quake shared a video highlighting his team’s latest advances in spatial transcriptomics: the ability to label panels of genes in a large cross-section of the brain and be able to zoom in from the whole brain slice to a particular subregion like the hippocampus, then zoom in again to see individual hippocampal cells, and finally reaching the molecular level, enabling viewers to count individual RNAs within a cell — all still in the context of intact brain circuits and neuroanatomy.

Quake’s lab, in collaboration with the lab of Stanford Medicine’s Thomas C. Südhof, has been working for many years to unravel RNA’s role in long-term memory creation. Using genetically modified mice engineered by Luo’s lab to tag brain cells activated during a particular behavior, Quake’s team has been able to identify cells involved in the formation of a specific memory in mice as well as the specific genetic signatures that changed in these cells during learning. Using the power of spatial transcriptomics, they also noted changes in nearby non-neuronal glial cells called astrocytes, which also appeared to play a role in memory formation.

Almost as an aside, Quake noted an interesting insight into how long-term memory can be affected by social factors. Mice tend to prefer chocolate over cinnamon, but when Quake’s lab allowed untrained mice to interact with mice trained to prefer cinnamon, the chocolate-loving mice became cinnamon lovers too. Quake hasn’t yet learned exactly how the mice transfer the preference.

“We’re just about to tease apart some really interesting things—not just memory, but cognition, sleep, things like that, other aspects of behavior.”

Toolmakers

All the findings presented thus far relied on advances in spatial transcriptomics as well as exciting advances in AI technology — often necessary to extract the subtle patterns of gene expression that define distinctive cell types. The final presentations were given by toolmakers whose research promises to expand the potential of transcriptomics even further.

The job of sorting and assembling the immense amount of data produced by transcriptomics is made easier by cutting-edge AI tools. Neuro-omics Initiative member Jure Leskovec, a professor in the Department of Computer Science, previously worked with Quake to develop one such AI tool, the Universal Cell Embeddings project which analyzed transcriptomic data from 36 million cells to uncover how cell types from many species are organized.

Yanay Rosen, a graduate student in the Leskovec lab, presented a next step in the campaign to categorize and understand human cells. The AI Virtual Cell, a project by the SNAP Research Group, aims to produce an AI model that simulates all the biological processes within a cell, which could be used to conduct high-throughput virtual experiments that would be too challenging, costly or time-consuming with real cells.

The challenge for such AI models is finding enough data to make them as accurate as possible. Neuro-omics co-director Alice Ting, professor of genetics, biology and chemistry in the Stanford schools of Medicine and Humanities and Sciences, presented yet another advancement in RNA sequencing that may help fill the data gap. Ting and colleagues developed a technology called single cell APEX-seq (“scAPEX-seq”) to map the location of RNA within cells at the nanometer scale. Ting showed how she and her colleagues were able to map RNA transcripts within cancer cells with greater accuracy than conventional RNA sequencing methods, which may lead to more effective immunotherapy treatments.

Ting wasn’t done unveiling new tools. Her lab has also developed a new neuron-silencer called LATeNT. Conventional neuron-silencers (tools that prevent synapse transmission used to study the function of specific neurons) don’t allow for both precise timing and sustained effect. LATeNT is a modified tetanus toxin that achieves both and is highly customizable. It can be triggered by external light (or bioluminescence from genetically expressed enzymes), by drugs or based on a cell’s prior activity. Ting believes that it offers an array of synthetic biology applications including neuron suppression and light-activated protein transcription.

More to come

Over just a few hours, the 2024 Neuro-omics Symposium presented a dizzying array of progress in ‘omics technology development and its applications to our fundamental understanding of the brain’s evolution, circuitry, and function. Much of the research presented is still at the earliest of stages, and thus promises many more exciting discoveries to come.

“With ever-more powerful tools being developed, we can only imagine how much more we’ll be able to probe into the mysteries of the brain,” Luo said.