Neuro-omics initiative sheds light on how neuronal connections are formed

Connections are important. We humans are social animals that rely on family, friends and acquaintances to survive and thrive. Likewise, our brains are also completely dependent on connections.

Each brain cell, or neuron, forms multiple physical contacts with other neurons in the brain in order to transmit information and encode memories. The average adult brain consists of over 100 trillion connections, with some neurons linking to thousands of other cells. Given that the human genome only encodes for some 20,000 or so genes, scientists have long wondered how neurons are able to make so many unique linkages with so few starting blocks.

The Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute-funded Neuro-omics Initiative aims to bridge the chasm between the building units of the brain and its higher-order architecture using powerful new approaches such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and machine learning. New work from Wu Tsai Neuro affiliate Liqun Luo and his lab uses a novel proteomics technique developed through the Neuro-omics initiative to understand how a limited number of genes can specify trillions of unique connections.

Scientists have long suspected that neurons use a handful of master regulators of gene expression, called transcription factors, to direct the formation of new connections. According to this model, transcription factors turn on different combinations of cell-surface proteins, which together specify a neuron’s directional growth. This combinatorial strategy would let two cells use just a few different molecules to join together with the exquisite specificity that a fully functioning brain requires.

In work published May 24, 2022 in Neuron, the Luo lab establishes experimentally for the first time that a single transcription factor can direct multiple unique wiring patterns by turning on different sets of genes. Working in the model organism Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, Xie et al. unravel the control network of one of these transcription factors — called Acj6 — and discover new surface proteins involved in directing neuronal wiring.

“Before, the link between transcription factors and the proteins expressed on the surface of the cell was missing—most people only looked at one cell-surface protein and one transcription factor in isolation. No one had systematically looked at the set of all cell-surface proteins expressed on different types of neurons,” said Qijing Xie, a neurosciences graduate student who was co-lead author of the new study. “We demonstrated that unique combinations of cell-surface proteins, regulated by the same transcription factor, are expressed in different neurons and direct the formation of neuronal connections.”

“The cell-surface proteomics platform we developed two years ago as part of the Neuro-Omics Initiative was essential for this work,” added Luo. In this technique, product of a collaboration between the Luo lab and the lab of Alice Ting, a Neuro-omics Initiative member, researchers tag only those proteins that appear on the surface of a cell using a method called proximity labelling, and then use mass spectrometry to determine protein identity. Crucially, this work is done on intact tissues with the type and location of the neuron being profiled is known, making it possible to link a given set of cell-surface proteins with its corresponding neuronal connection.

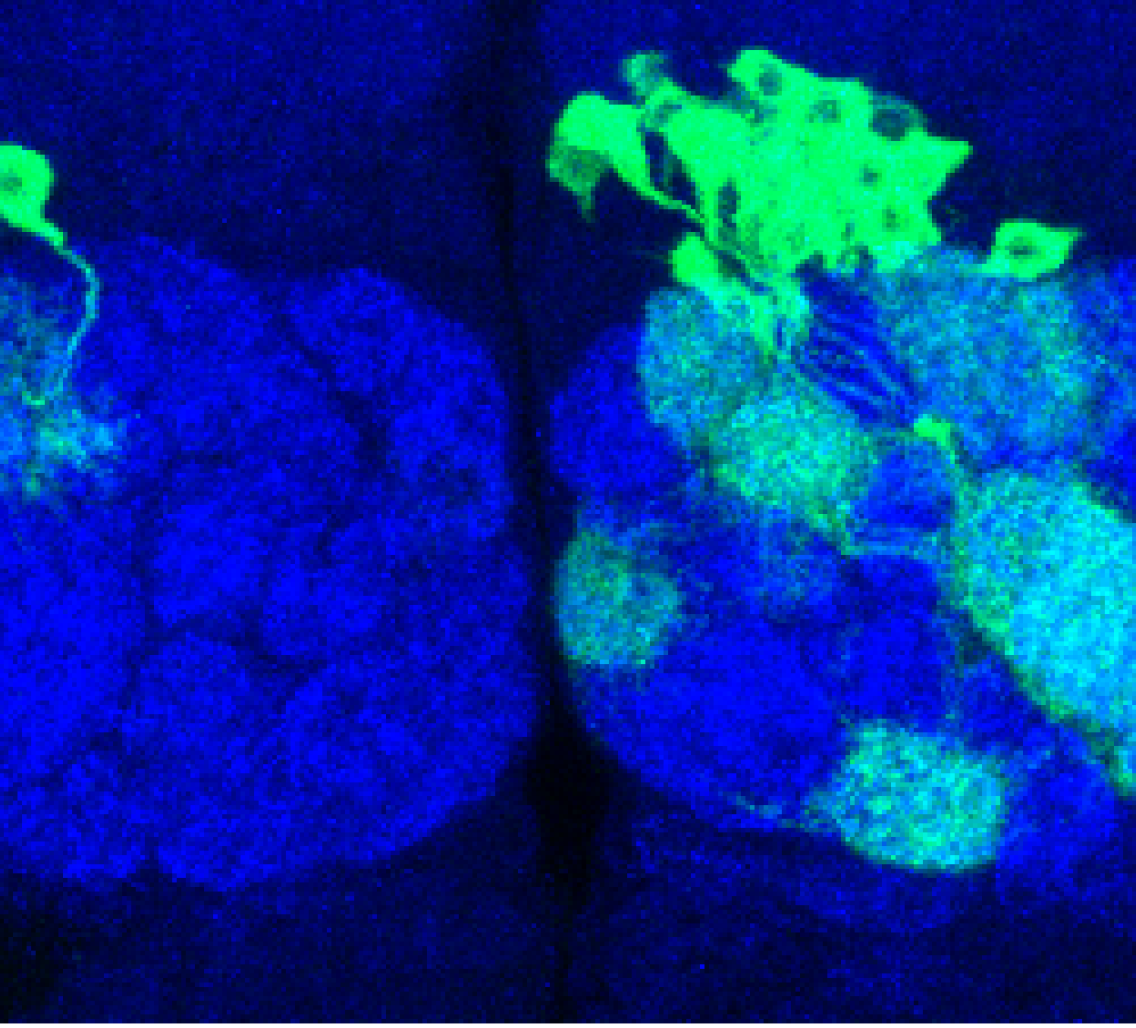

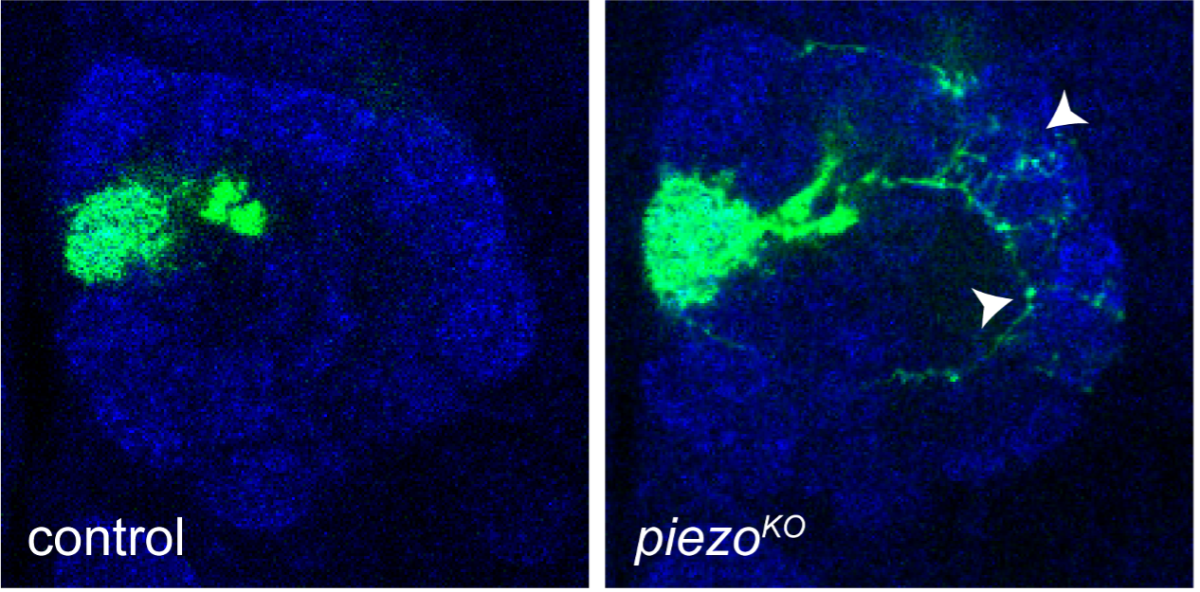

Deleting Piezo, a force-sensing ion channel, causes neurons (labeled in green) to go beyond their own “territories” and form incorrect connections (arrowheads). Blue staining shows the antennal lobe where 50 types of olfactory projection neurons collectively receive their input from partner olfactory receptor neurons. Image credit: Luo Lab.

Although the current work applies this proteomics technique to neurons, co-lead author Jiefu Li, a former graduate student in the Luo lab, expounded on the many possible applications of the method: “This technique can be easily extended to other questions. I’m setting up my own lab at the HHMI Janelia Research Campus, where we’ll use these tools to study the immune system and cancer.”

This pioneering work was the result of close collaborations between the Luo lab and Neuro-omics Initiative members Steve Quake and Alice Ting, who were co-authors on the new paper, and provides fodder for many future areas of investigation in neuroscience. “One of the reviewers told us, nicely, that our study has more information than all the previous papers on this topic added together,” Luo remarked with a smile.

Luo is the Ann and Bill Swindells Professor in the Department of Biology and an HHMI Investigator. He is a member of Stanford Bio-X, Sarafan ChEM-H, the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Ting is Professor of Chemistry and Biology. She is a member of Stanford Bio-X, Sarafan ChEM-H, the Stanford Cancer Institute, theMaternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI)and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-DC005982; R01-DK121409), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and a Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Big Ideas in Neuroscience award.