Stretchy, conductive electrodes that can keep up with an octopus

By Katherine Bourzac

Materials for bioelectronics must often compromise between mechanical and electrical properties. In a talk at the ACS Fall 2022 meeting, Stanford University chemical engineer Zhenan Bao described her approach to designing polymers that bridge that gap, combining high electrical conductivity with soft, stretchy, tissue-like mechanical properties.

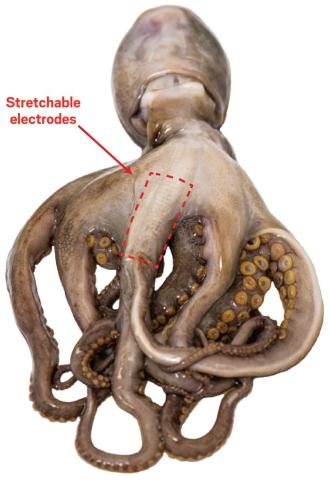

With careful chemical engineering, Bao’s group has made conductive-polymer electrodes that can stimulate single neurons in the brain stem without harming its delicate tissue. They then used the electrodes to measure electrical activity in an octopus’s muscles as the creature stretched and swam. Bao presented this work in the Division of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry on Monday.

Conductive polymers are in some ways ideal for making bioelectronics. Unlike conventional electronic materials, such as silicon and metal, they can be inherently soft and stretchable. But improving their electronic properties typically comes at a cost: the more crystalline a polymer is, the higher its electrical conductivity—and the less it will stretch.

Bao and her team decided to separate out these competing priorities by developing a polymer that interlocks separate parts, each optimized for conductivity, mechanical properties, or photopatternability.