Q&A: GVVC director Nicholas Wall has a passion for nature's genetics toolkit

The Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute is pleased to welcome Nicholas Wall, PhD, as the new director of the Gene Vector and Virus Core (GVVC), which supports the Stanford neuroscience community through production of powerful viral genetic engineering tools.

Engineered viruses have been a central driver of a revolution in genetics over the past few decades. In nature, viruses are little more than gene delivery mechanisms, programmed by evolution to smuggle their own DNA or RNA into a host cell, turning the cell into a factory for replicating the virus. Scientists have leveraged this ability to create viral tools capable of a wide variety of genetic tricks — inserting, deleting, or modifying genes of interest in cells or whole organisms.

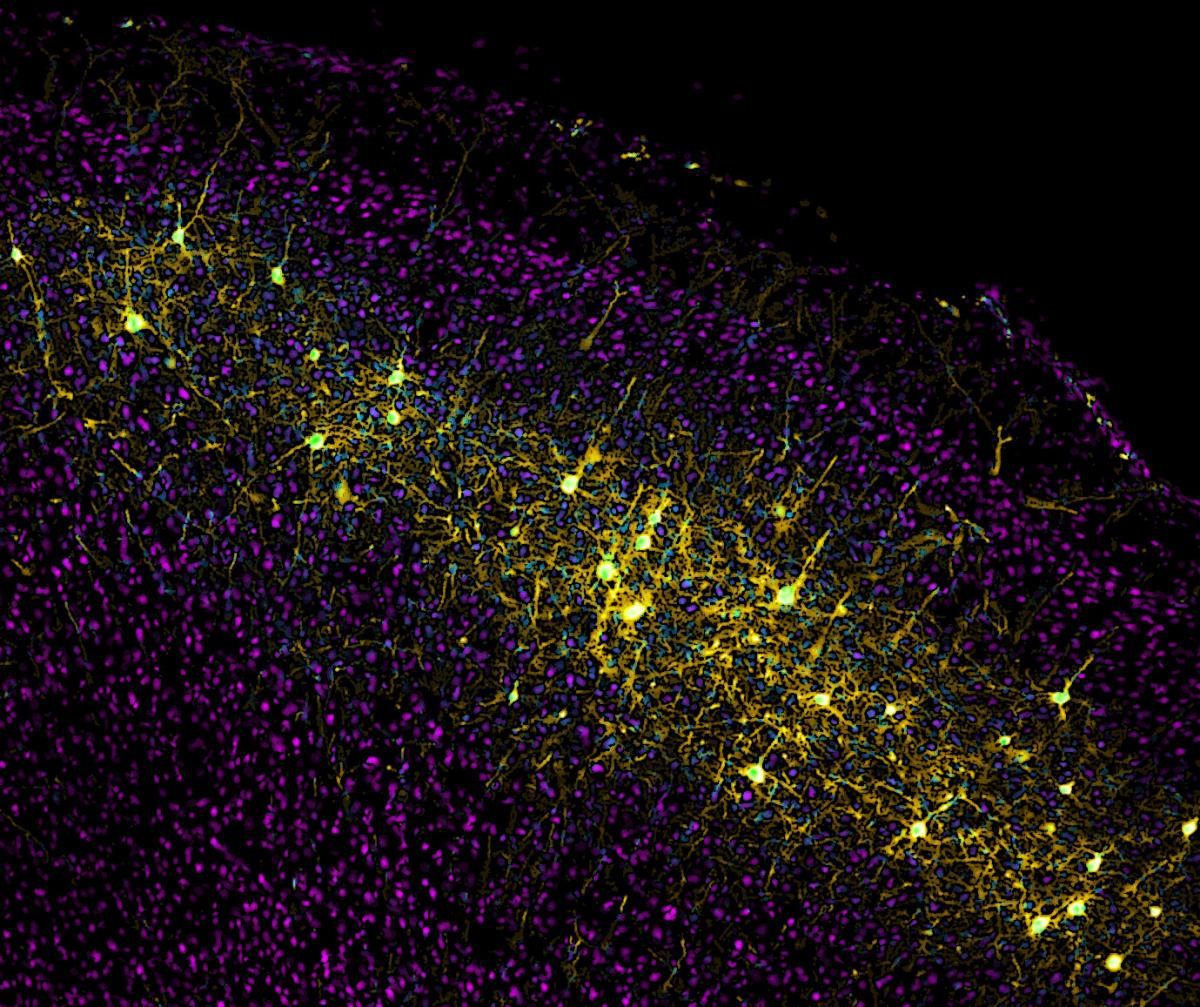

As part of Wall’s doctoral work with neuroscientist Ed Callaway at UC San Diego, he designed a blockbuster viral toolkit for precisely mapping the wiring of the brain. The lab had previously developed a clever system for harnessing the rabies virus’s deadly ability to spread through the brain from synapse to synapse as a way to trace incoming connections to particular types of neurons. However, lab scientists had only begun to demonstrate the system’s potential in a petri dish, which cannot compare to the enormous complexity of the mammalian brain. Wall developed a two-virus system that enabled the mapping of intact brain circuits, ensuring that the rabies virus could only spread across a single synaptic connection, and only in the presence of an experimentally introduced transgene. Both safer and more precise than ever, the tool has since been taken up by hundreds of labs around the world.

Cortical neurons that send projections to the striatum are labeled in yellow by Wall's monosynaptic rabies virus system.

Image courtesy Nicholas Wall.

More recently, Wall worked at Stanford as a postdoc and research scientist in the Nancy Pritzker Laboratory, directed by Robert Malenka, MD, PhD, where he has continued to use viral circuit tracing techniques and other virus-based tools for studying and manipulating the activity of brain networks implicated in addiction to cocaine and other drugs of abuse.

Wall stepped into the role of GVVC director in May 2022, succeeding the facility’s previous director, Javier Alcudia, Ph.D. The GVVC is one of Wu Tsai Neuro’s six Neurosciences Community Laboratories, facilities that go beyond the typical research core by providing a hub of expertise and collaboration for researchers across campus and beyond. Each core is directed by an experienced scientist with deep knowledge of their field who can help design and facilitate projects for researchers of all levels of expertise.

“Nick has got such an outstanding background to take on leadership of the GVVC,” said Tim Doyle, D.Phil, Wu Tsai Neuro assistant director for the Neurosciences Community Labs. “He is a trained neuroscientist who has extensive experience developing novel virus constructs for his research, and can bring new offerings to the community that we don't currently have available."

Wall says he looks forward to being a ‘force multiplier’ to advance Stanford neuroscience research by getting cutting edge tools into the right hands and working with scientists to help them identify the best way to accomplish their research goals.

We spoke to Wall about his love of viruses as a research tool in neuroscience and his goal of being a ‘force multiplier’ to advance neuroscience research at Stanford and around the world.

What attracted you to the GVVC position?

As a grad student in Ed Callaway’s lab at the Salk Institute, I led the development of a system for cell-type specific circuit tracing in the intact brain using a modified rabies virus. It took maybe a year and a half to get this working in our own hands, but we wanted to make sure these tools became a bedrock of neuroanatomical analysis, so we spent years more making the system more robust and reliable.

During that period I realized that I loved the technical side of virus production, iteration, and innovation. There's a lot of fulfillment in being able to see the time, effort and care that you put into making tools that can facilitate so many other people's research. I wasn't just moving forward my little project — as this toolkit was taken up by hundreds of other labs, it felt like my contribution to the field was amplified dramatically.

That’s how I see my role at GVVC: as a force multiplier to help push forward fundamental and translational neuroscience research for the Stanford community.

How has the use of viruses changed in the past decade that you’ve been working with them?

There used to be some nervousness around using viruses, but I think that’s been largely overcome as they’ve become an integral piece of the experimental neuroscience toolkit. Everyone is using them nowadays, and we’ve made a lot of strides in ensuring these tools are safe to handle. Adeno-associated viruses in particular, also called AAVs, are so safe that they’ve become the standard for human gene therapy trials.

Now the more common fear is uncertainty about finding the right tool for the job. That’s where virus cores and production facilities like GVVC have stepped up to the plate. With the efficiencies of scale and expertise they bring, they help overcome the energy barrier of "is it worth the investment?"

A lab’s investment is no longer 18 months of a graduate student’s PhD developing a virus and testing its validity. Now you can just say, ‘This is the transgene I need and where I want to express it — what’s the best tool for the job and can I get it in a couple weeks?’ And the answer is, ‘Yes you can.’

Can you tell me about how you’ve used viral vectors, as a postdoc in the Malenka lab here at Stanford? Were you a GVVC customer?

One of my major projects was studying how the powerful experiences elicited by drugs of abuse such as cocaine recruit a very broad, very fast network of synaptically connected cells across the brain. For this project we used AAVs from GVVC as well as the in vivo monosynaptic rabies virus system I developed in the Callaway lab, which allowed us to build these beautiful brain-wide maps of the connectivity of these experience-activated cells. These viral tools inspired a new hypothesis about specific pathways most relevant to behavioral addiction or substance abuse. And then we were able to use another set of viral tools — AAVs with proteins that allow for the precise control of populations of brain cells with either light or designer chemicals — to show that manipulating this pathway could selectively alter animals’ behavioral response to cocaine.

Basically every stage of this project involved using AAVs and/or rabies virus, from the basic anatomy to studying the network’s physiology, to manipulating behavior using opto- and chemogenetic stimulation or silencing of neurons. I don’t think that’s uncommon. Viral vectors have become so fundamental to people’s work that it’s hard to imagine a world where we didn't have these tools — it would be quite a blow for the field!

Viruses are just these really efficient gene delivery tools developed by nature that are better than anything we could develop ourselves. The fact that we’ve been able to harness the power of viruses is still incredible to me!

How do you see GVVC's role in advancing Stanford neuroscience research? What's your message for existing and potential future users?

Coming into this role, I feel two responsibilities. One is to existing, experienced users who need to get their tools as quickly and efficiently as possible. I’m focused on maintaining high quality, reliability and consistency from batch to batch, which is an important concern for our users.

When it comes to new investigators, folks not trained in viral vectors, who may not come in knowing the right tool for the job, it's about offering full-service experience. With my background in both virus development and neuroscience, I can sit down with people and go into the nitty gritty details of their needs to identify the tools that are going to be the most likely to help them answer their research questions. My job is to be a facilitator: to make sure investigators can go from any starting point to being able to conduct the experiments they want to do as quickly as possible, whether we have the right tool in stock or need to go and build it.

That's what people want in the end: they want tools that are robust and reliable that don’t require months of troubleshooting. Of course there’s always some need for iteration when working from new hypotheses with new tools, but my goal is to reduce the energy barriers so people can effortlessly get the tools they need and just go.

Sounds like you’re excited to get started!

I am! One thing I’m really looking forward to is the institute retreat later this month: I’m excited for the opportunity to sit down with people and chat about their work and how we can support them. That's really what I like to do: I could just talk about viruses all day!