NeuroChoice: Eight years of forging connections to illuminate and empower choice

Choice is how we fashion ourselves, our lives, and our societies — how we navigate into the future. Some choices can elevate us, while others risk destroying everything we value. And yet, for all that we know about the brain and mind, science is often equivocal when explaining how and why people make the decisions they do — particularly the self-destructive decisions of people locked in the grips of substance abuse and addiction.

Eight years ago, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute’s flagship “Big Ideas in Neuroscience” grant program launched the Stanford NeuroChoice Initiative. The objective was to build a community across traditional disciplinary boundaries that would deepen understanding of how people make choices. As the project evolved, it began to ask how the neuroscience of choice reflected on the widespread epidemic of addiction and overdose.

The Initiative’s founders discovered that much of the ongoing research into addiction and overdose was being conducted in isolated academic silos. The underlying neurobiology of addiction, its social psychology, and drug policies designed to combat the epidemic, were each the distinct expertise of different groups of scholars, who used different methodologies, reported their findings in different scientific “languages”, and attended different scientific conferences. Like early world maps, each discipline faded at the edges into fuzzy speculation and warnings of “here be dragons.” Thus disconnected, new discoveries were often trapped in non-overlapping scientific communities, slowing or stalling real-world progress in addiction treatment.

The Neurochoice team pivoted their Big Idea, realizing that by connecting the best researchers across disciplinary boundaries — training them to understand one another, sharing data, and spurring new collaborations — they could accelerate progress addressing the drug-use crisis and fill in the hazy corners of our understanding in the process.

The NeuroChoice Insight

NeuroChoice was founded to bridge gaps between three distinct levels of inquiry. “We wanted to create a generative dialogue between fundamental scientists, clinicians, and policymakers – and to turn the knowledge emerging from those conversations and the studies they prompt into treatments and practices, particularly those that can help people suffering with substance-use disorder,” said Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute affiliate Brian Knutson, a professor of psychology and co-director of NeuroChoice.

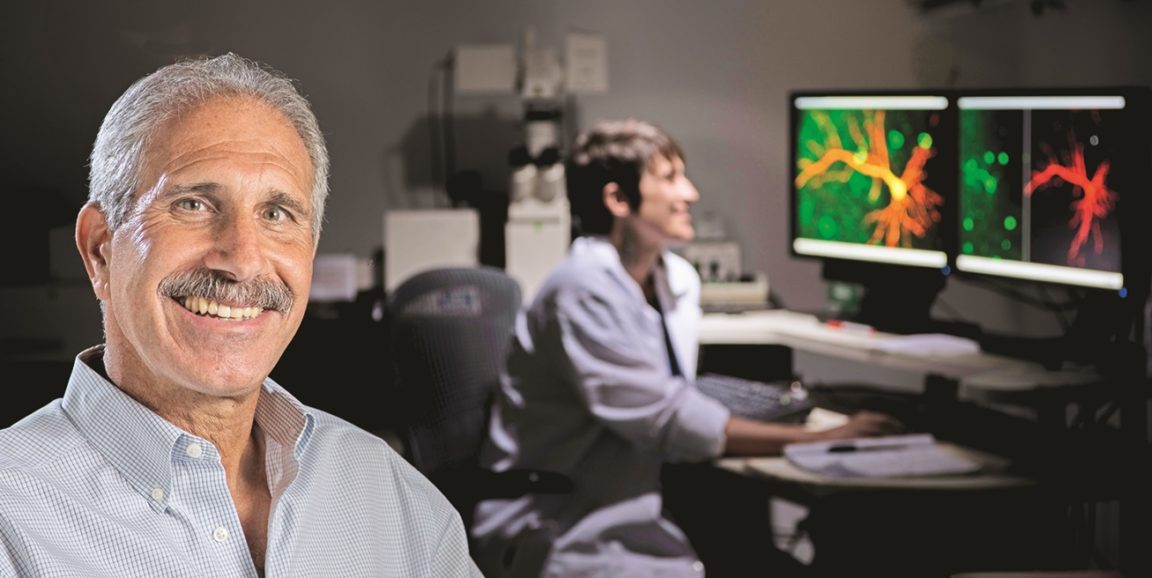

To supercharge the effort, Knutson and his NeuroChoice co-directors Robert Malenka and Keith Humphreys assembled a multidisciplinary team. They drew from Stanford scientists conducting basic research into the molecular foundations of addiction, others who conduct clinical research and practice in the field, and public policy experts who guide treatment and funding priorities in the world of addiction treatment. “The community we constructed brought together dozens of researchers from virtually every school across the Stanford campus,” said Knutson.

Through these connections among disciplines, knowledge, data, and insights can travel from the most mechanistic biological studies to the most holistic policy conversations — and back — said Malenka, who is the Nancy Friend Pritzker Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford Medicine and a founding member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute executive committee. Molecular biologists can help those working on the clinical and policy levels with insights derived from neuroscience. Likewise, insights and questions from the world of policy can spark new avenues of basic research. Flow in both directions better aligns the whole enterprise — advancing discovery science as well as more effective policy aimed at helping those with substance use disorders.

Malenka and other basic science researchers involved in NeuroChoice study animal models to identify structural and functional processes in deep brain circuits that contribute to the development of addiction, to withdrawal, and to addictive relapse. Knutson and his colleagues use neuroimaging to analyze those same deep circuits in human research subjects and clinical populations, assessing whether and how they may also be associated with substance addiction and relapse. Humphreys and colleagues working at the policy level synthesize insights from basic and clinical work into policy recommendations, conveying them to stakeholders in government and policy circles, and soliciting feedback on what is most useful and what should be the focus of further investigation.

Real-world application

As an example of clinical-level insight guiding molecular research, clinicians and psychologists have long observed the propensity of human patients suffering from withdrawal symptoms to become acutely asocial during the make-or-break first days and weeks of withdrawal after they have quit using an addictive substance. It is an agonizing irony that this often occurs just when people with addictions most need the support of, say, 12-step sponsors, family members, or healthcare workers. The social isolation that accompanies withdrawal makes relapse much more likely, said Humphreys, who is the Esther Ting Memorial Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

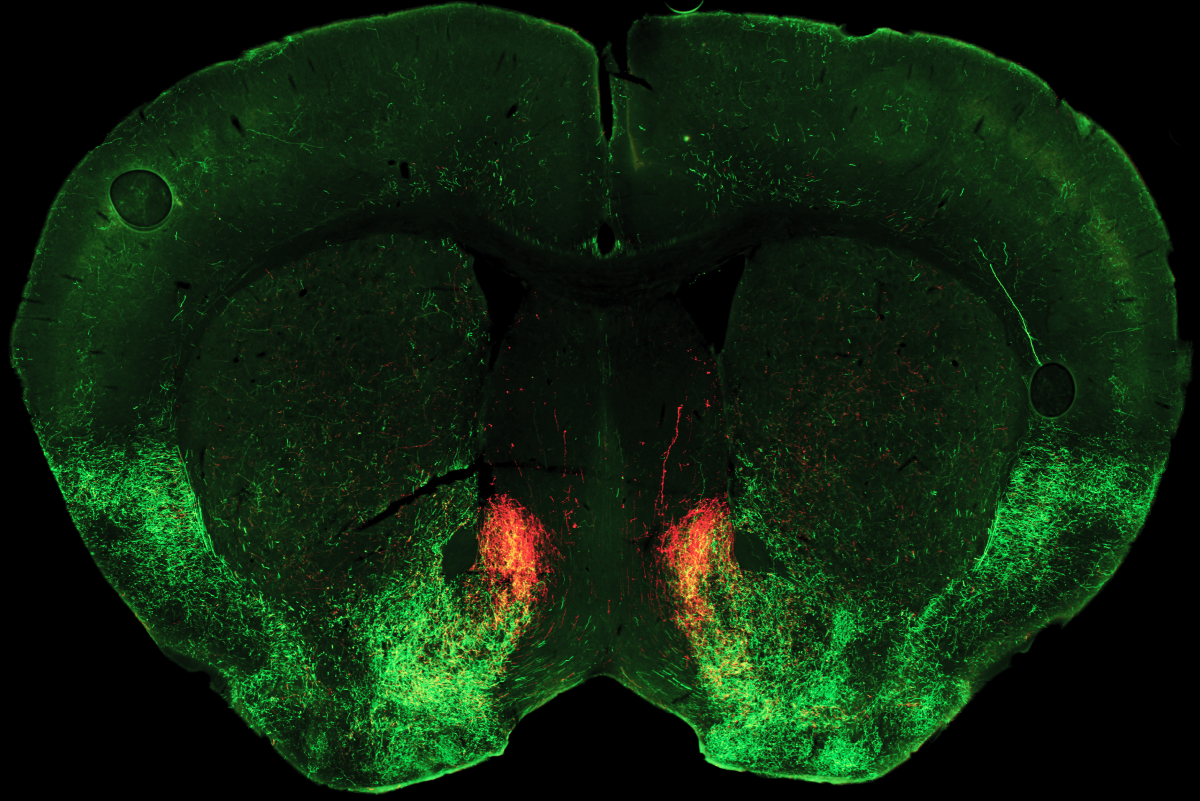

Responding to this clinical observation, Malenka, who’d already established a link between asociality and inhibited serotonin release, set his lab to study the same neural mechanism for a mouse model of opioid withdrawal. Postdoctoral scholar Matthew Pomrenze found that during opioid withdrawal, a neuropeptide chemical called dynorphin activates kappa opioid receptors, a type of opioid receptor molecule, and blocks serotonin release in the nucleus accumbens. This molecular chain reaction causes mice in opioid withdrawal to exhibit asocial and depressed behavior.

“Maybe this is also what causes the asocial behavior we see in human withdrawal,” Malenka said. “So, to make the experiment more clinically relevant, we asked — If we gave the animals a drug that blocks this kappa receptor and restores serotonin release, could it also restore normal levels of sociability?”

The team gave their asocial mice a kappa receptor blocker called aticaprant — which is already being tested for the treatment of certain subtypes of depression in humans. “It completely reversed their sociability deficits,” said Malenka.

“Achieving something similar for humans could have a profound impact on the opioid epidemic,” said Humphreys. A sociality-enhancing medication could give clinicians a tool to help those who have kicked substance use disorders to stay in contact with those who can help keep them from relapsing. Understanding the potential for such a medical intervention could also help policymakers and program administrators take advantage of potential new levels of social connection when supporting people with substance disorders through early abstinence.

This is just one example where contact and collaboration between researchers working at different levels, and with different toolsets, has led to breakthroughs. Without NeuroChoice’s efforts, Knutson emphasized, many of these advances would not have occurred, or would have taken much longer.

“Another aspect of the Big Ideas Initiative is that it provided funding allowing us to track and predict long-term outcomes in people suffering from addiction,” Knutson said.

For instance, based on the circuitry outlined by Malenka’s team, Knutson and colleagues were able to identify neural activity and structures that predict relapse to stimulant use disorder. Similarly, Initiative co-investigator Claudia Padula in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science was able to leverage these findings to predict relapse to alcohol use disorder. The ability to make these predictions, in turn, highlighted targets for intervention. In fact, Padula and Initiative co-investigator Tim Durazzo, also in Psychiatry, are currently testing non-invasive transcranial magnetic stimulation as a tool for reducing relapse in people with alcohol use disorder.

Seeing the Bigger Picture

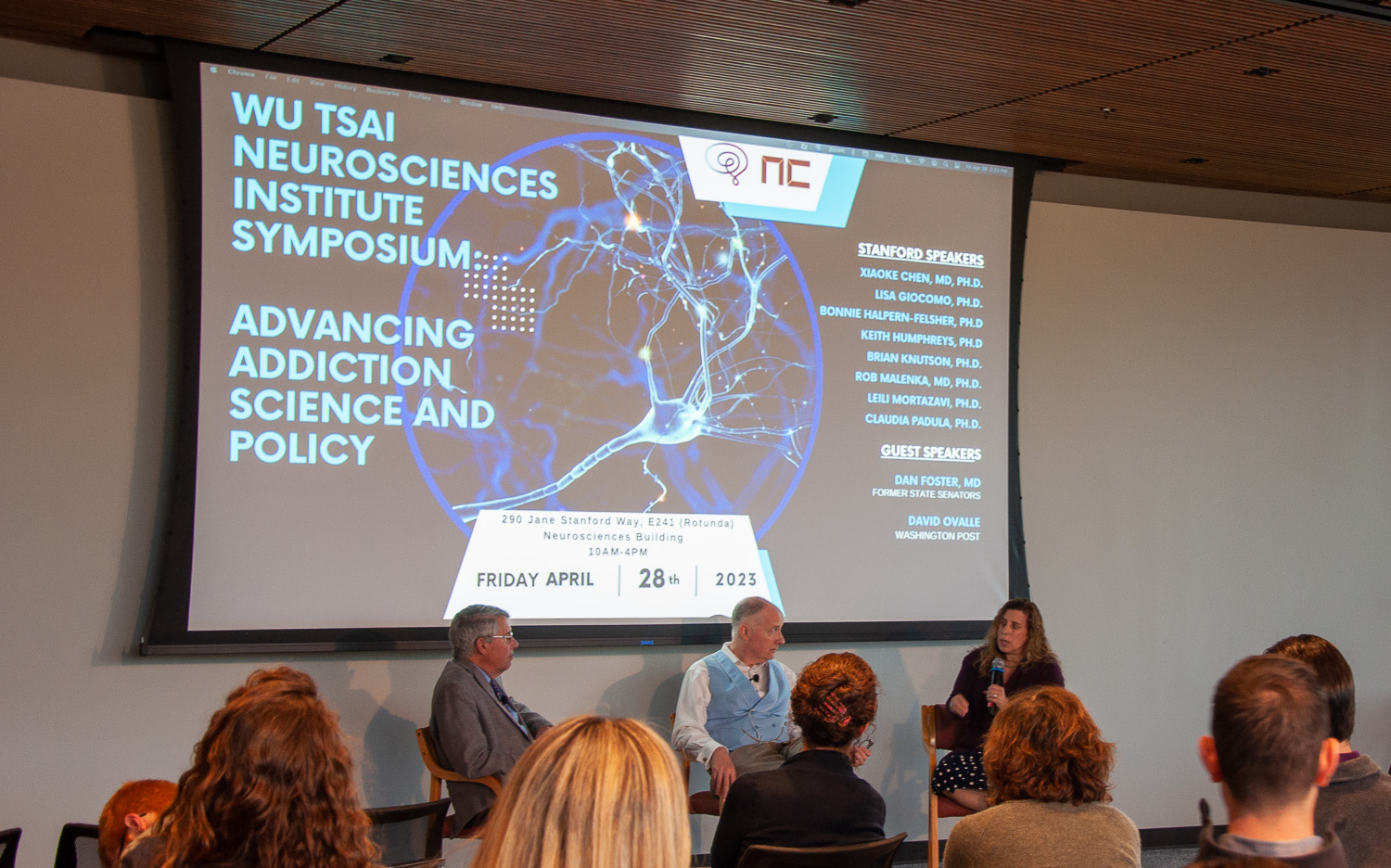

When the Big Idea funding from Wu Tsai Neuro officially tapered off in 2023, Initiative leaders marked the occasion with a day-long symposium called “Advancing Addiction Science and Policy,” which highlighted the program’s accomplishments over the past eight years — kind of a big picture of the Big Idea.

There was much to report: the publication of dozens of groundbreaking papers by NeuroChoice researchers; important congressional testimony in the U.S. and abroad; the formation of key translational insights; the development and application of powerful new molecular tools — such as optogenetics and viral tracing — to the study of addiction-relevant research; the hosting of weekly cross-disciplinary talks, periodic meetings, and semi-annual symposia.

The program also contributed to the formation of the Stanford Network on Addiction Policy (SNAP), co-chaired by Humphreys. “SNAP brings scientists, policymakers, and the public together to form scientifically-informed policy recommendations for preventing and treating substance use disorders, supporting long-term recovery from addiction, and protecting public health and safety,” said Humphreys.

Finally, NeuroChoice trained dozens of young scientists to think and reach outside their disciplinary silos to advance their work. “The creation of this new generation of cross-disciplinary addiction collaborators may be the program’s most profound and lasting legacy,” said Knutson. “While much of the translational discussion happened at our talks and dinners,” he said, “the more focused collaborations happened between labs, usually with a graduate student or postdoctoral fellows as the ‘glue’ holding the pieces together.”

Happily, the work of the NeuroChoice community continues! A recent philanthropic gift to the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences will allow the research to continue advancing cross-disciplinary approaches and contributing new insights to the field of addiction medicine.