Octopus Brains

One of the incredible things about octopuses is that not only do they have an advanced intelligence that lets them camouflage themselves, use tools and manipulate their environments and act as really clever hunters in their ecosystems, they do this with a brain that evolved essentially from something like a slug in the oceans hundreds of millions of years ago.

Our brains share virtually nothing in common with theirs. The question for scientists is what can studying a creature with a completely different brain from our own, teach us about the common principles of what makes a brain, what makes intelligence? What does it mean for this creature to have an intelligence that is something like our own?

To learn more, we spoke this week with Ernie Hwaun and Matt McCoy, two interdisciplinary postdoctoral scholars at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford who study cephalopod intelligence from completely different angles.

Listen to the full episode below, and SUBSCRIBE on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music or Stitcher. (More options)

Links

Q&A: Evolution of octopus and squid brains could shed light on origins of intelligence

Stretchy, conductive electrodes that can keep up with an octopus

Andrew Fire lab (Stanford Medicine)

Ivan Soltesz lab (Stanford Medicine)

Marine Biological Laboratory Cephalopod Initiative

Acknowledgements

Ernie Hwaun's research has been supported through a Stanford Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Interdisciplinary Scholars Award and ONR MURI grant N0014-19-1-2373.

Matt McCoy's research has been supported through a Stanford Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Interdisciplinary Scholars Award, the Stanford Genomics Training Program, and several programs at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, including a Grass Fellowship in Neuroscience, a Whitman Early Career Fellowship, and the Cephalopod Initiative.

Episode Transcript

Nicholas Weiler:

This is From Our Neurons to Yours, a podcast from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University. On this show, we crisscross scientific disciplines to bring you to the frontiers of brain science. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler. Here's the sound we created to introduce today's topic, cephalopods.

What can octopus and squid brains teach us about intelligence?

One of the incredible things about octopuses is that not only do they have an advanced intelligence that lets them camouflage themselves, use tools and manipulate their environments and act as really clever hunters in their ecosystems, they do this with a brain that evolved essentially from something like a slug in the oceans hundreds of millions of years ago.

Our brains share virtually nothing in common with theirs. The question for scientists is what can studying a creature with a completely different brain from our own, teach us about the common principles of what makes a brain, what makes intelligence? What does it mean for this creature to have an intelligence that is something like our own? And that brings us to today's guests.

Ernie Hwaun:

My name is Ernie Hwaun. I'm a postdoctoral research fellow at Stanford. I'm in Yvonne Schulte's lab, and we've been studying octopus for the last three years.

Nicholas Weiler:

And how about you, Matt?

Matt McCoy:

My name's Matt McCoy. I'm a postdoc at Stanford. I'm in Andy Fire's lab, and our lab has not studied octopus or cephalopods before, but I'm studying gene size and particularly gene size evolution during nervous system evolution. That brings us to the cephalopods because they do something very unique among invertebrates.

Nicholas Weiler:

Which is what?

Matt McCoy:

Well, so vertebrates have evolved some of the largest genes. So their genome has expanded greatly compared to most other invertebrates, and their gene sizes have also evolved or expanded greatly, just like invertebrate evolution.

Nicholas Weiler:

So I want to start by just asking for your perspective on this. How intelligent are these animals, octopi, squid, cuttlefish, and how do we know and how do define intelligence in an animal like this?

Ernie Hwaun:

Yeah, so broadly speaking, it's really the ability to make predictions based on your prior experience and knowledge. These animals are quite intelligent because they possess complicated behaviors. They have to hunt in the open seas and they can camouflage, and their bodies are all soft. So there's actually no rigid shells to protect them. So they really evolved a different way to basically survive in a really competitive environment, and that is to have a sophisticated nervous system that enable them to do all sorts of complicated behaviors. So like you mentioned before, an octopus can take the tools in the environment. And pretty nice example is the coconut. Octopus can take the coconut shells and use it as a temporary shelters in the open sea.

Nicholas Weiler:

Sort of showing this problem-solving ability that they can take what's around them and figure out solutions to protect themselves. How do we think octopi and squids and cuttlefish got to be so smart? As I mentioned, they evolved from slug-like mollusks millions of years ago. Matt, since you're studying octopus evolution, what do we think is going on here?

Matt McCoy:

So yeah, the question, how did the cephalopods get so smart? I think it's useful to reframe this question. So cephalopods are mollusks, like you said, which excepting the cephalopods altogether, are not so intelligent. So, how did the cephalopods get so smart evolving from these slug-like mollusks? I think when we ask it in this way, it implies that humans as vertebrates did not also evolve from the same common ancestor with cephalopods, which in fact, we did.

Our common ancestor was likely a simple worm-like creature with a very simple nervous system, living on the sea floor some 600 to 800 million years ago. What's so fascinating is that since diverging from that common ancestor, vertebrates and cephalopods independently of all the complex nervous systems. So this is really the question, how did they independently evolve intelligence? And so we're interested in the differences in how this happened, but also in the similarities in how this happened because it helps us learn about some of the fundamental principles of how intelligence evolves.

To answer this question, my research focuses on the genetics and the evolutionary biology underlying nervous systems. And so researchers sequenced the human genome something like two decades ago now, but they haven't stopped sequencing since then. The technology's just getting faster and cheaper. And so researchers have been sequencing the genomes of any and all of the most interesting organisms, including the cephalopods.

There are now several complete genome assemblies for cephalopods, and my research leverages these to compare their genomes with other animal genomes like ours. One of the clearest results that I've been uncovering is the size and complexity of genes in the genome. So we thought for a long time that vertebrate genomes were more complex than invertebrate genomes, but as it turns out, the genes of cephalopods independently became large and complex, so particularly the genes important for nervous system development and function, which is just like what occurred during vertebrate evolution, especially in humans. So we currently think that one of the things you need to evolve a complex nervous system, and consequently intelligence, is the complexification of the underlying genetic components.

Nicholas Weiler:

So both vertebrates with large brains and cephalopods, these large brain mollusk, have evolved these large genes, which seem to be somehow underlying or scaffolding the ability of forming complex nervous systems. Something like that.

Matt McCoy:

That's right. That's right. Yeah.

Nicholas Weiler:

Well, I want to hear a little bit more about just how different the octopus brain is from the mammalian or vertebrate brain. And they do some similar things to what we see in mammals, clever hunting strategies, camouflage using tools. But Ernie, they're their brains are pretty vastly different from ours, aren't they?

Ernie Hwaun:

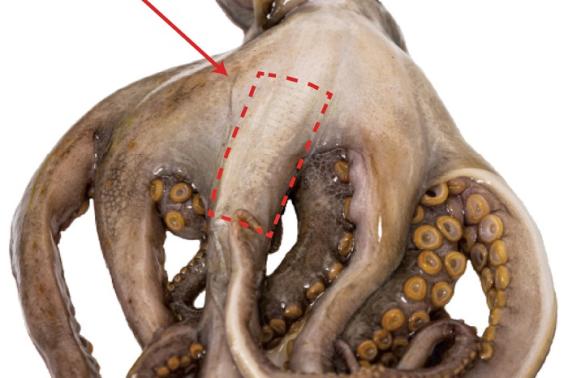

Yes. So one very obvious difference is the way they organize their nervous system. So they have a very distributed nervous systems. So in octopus, about two third of their 500 million neurons resides in the periphery nervous systems. And that is a very interesting body plan because when you consider the components that they have to control, their periphery is actually a lot more compared to the vertebra because their body is soft. So their movement is basically, they have virtually unlimited degrees of freedoms where they can do all sorts of movement. And also along each arm there are many suckers that they can individually control.

Nicholas Weiler:

They can kind of be any shape they want.

Ernie Hwaun:

Yes, and I'm sure a lot of audience also see how the octopus can crawl through really tight space. So any hole that is bigger than their beak, they can actually ... went through it by moving their bodies. They're controlling a very different bodies compared to the vertebrae like us, where we have joint, and you're simply controlling the muscle attached to the joint. And so your movement is very limited in that sense.

Nicholas Weiler:

So they sort of have these distributed nervous systems, where I think you said two thirds of their nervous systems are in their arms.

Ernie Hwaun:

Yes.

Nicholas Weiler:

And I think you said they have about 500 million neurons, so that's obviously less than say a human brain, but what would you compare them to in terms of their ability to do problem-solving?

Ernie Hwaun:

So their brain size will be comparable to dogs.

Nicholas Weiler:

So given that they've got this different organization, they've got independent brain cells in their arms, that they have some level of independence, or is it like their brain is just spread through their body? Or are they different centers of-

Ernie Hwaun:

Yeah, so from that distributed layout of their nervous system, one thing that come out is that the control is also highly distributed. So there is a study where they isolate the arms and then provide electrical stimulation to the arm, and they were able to reproduce kind of a bending motion where you see the octopus use to catch a prey. That kind of movement doesn't require controls from the center nervous system. The instruction to produce that kind of motion is embedded in the periphery and probably what the center nervous system is just sending a goal signals and then the rest of the instructions can be complete by the periphery.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's so great. It's like you tell your hand, "I'd like some coffee. Go make me some coffee." And then you kind of check back in a little while later and it's like, "Do I have coffee yet? Okay. Maybe I need to send in another hand."

Ernie Hwaun:

Yeah, exactly.

Nicholas Weiler:

I love imagining this, and that sort of brings me back to this question of, they've got such different body plants, such different types of brains. Like we've said, they evolved from something like a sea slug. And I think, Matt, your point is a great one. We also evolved from a flatworm once upon a time, into mammals and primates and so on. I think we're more familiar with the concept that mammals are clever, so it's less of a surprise. But I'd love to hear more about, what can this teach us a about what intelligence means to have another example of how intelligence evolved separately?

Matt McCoy:

Yeah. I mean, so there is just so much to learn. I mean, we're just starting. Like you're saying, almost everything we know about how intelligence evolved, we know from studying vertebrates. And vertebrate brains all share the same evolutionary history. So in science, we call this an N of one. There's one observation. This means we can't really know if our intelligence necessarily arises from our brains being built exactly the way vertebrate brains are built. How much of this is necessary versus just a historical contingency?

If we could play back the tape of life, would intelligence evolve the exact same way with brains built just like ours? Unfortunately for us, we know that we're not alone. The cephalopods bring us to an N of two now. So they evolved to complex nervous systems and intelligence independently from us. So we now know of a different way in which intelligence can evolve.

So again, the similarities will teach us a lot about some of the fundamentals of how to build the complex nervous system. Perhaps you need to have really large complex genes, while the differences have the potential to show us what makes us uniquely human.

Nicholas Weiler:

One of the things that we see with intelligence is solving new problems. When we think about intelligence, it's like picking up something on the ground and figuring out a new way to use it given your circumstances. Is this something that we see in cephalopods? How much of their intelligence is sort of hardwired, and how much of it seems to be learned, and can they pass it on to other individuals?

Matt McCoy:

Yeah, I think this is perhaps one of the things that is uniquely human, or at least uniquely vertebrate. Because for a lot of octopus species, they have their eggs. The mother wait until the eggs hatch, and then the mother very quickly dies. And so none of the information from that previous generation that mother octopus learned, none of that's passed on. And so everything the octopus does is pretty much from a fresh perspective. That's very different from humans which are able to learn from each other and our ancestors, et cetera. So perhaps something different, fundamentally different.

Nicholas Weiler:

Great. You guys are fantastic.

Ernie Hwaun:

Thank you very much.

Matt McCoy:

Yeah, awesome. Thanks. This was fun.

Nicholas Weiler:

Thanks so much again to our guests, Ernie Hwaun and Matt McCoy. To learn more, check out the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at neuroscience.stanford.edu. For more info about our guests' work, check out the links in the show notes. This episode was produced by Michael Osborne with production assistance by Morgan Henniker and Christian Heinis. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler.