Q&A: Balancing top-tier science with activism – a conversation with Black in Neuro's Brielle Ferguson

Brielle Ferguson was already in her fifth year as a graduate student at Drexel University in Philadelphia before she saw a Black faculty member give a talk for the first time.

For Brielle, a Black scientist herself, the event had an impact. It made her realize how much she would have benefited from having more mentors and role models who looked like her, and it made her believe that, maybe, her dream of becoming a research professor could actually come true.

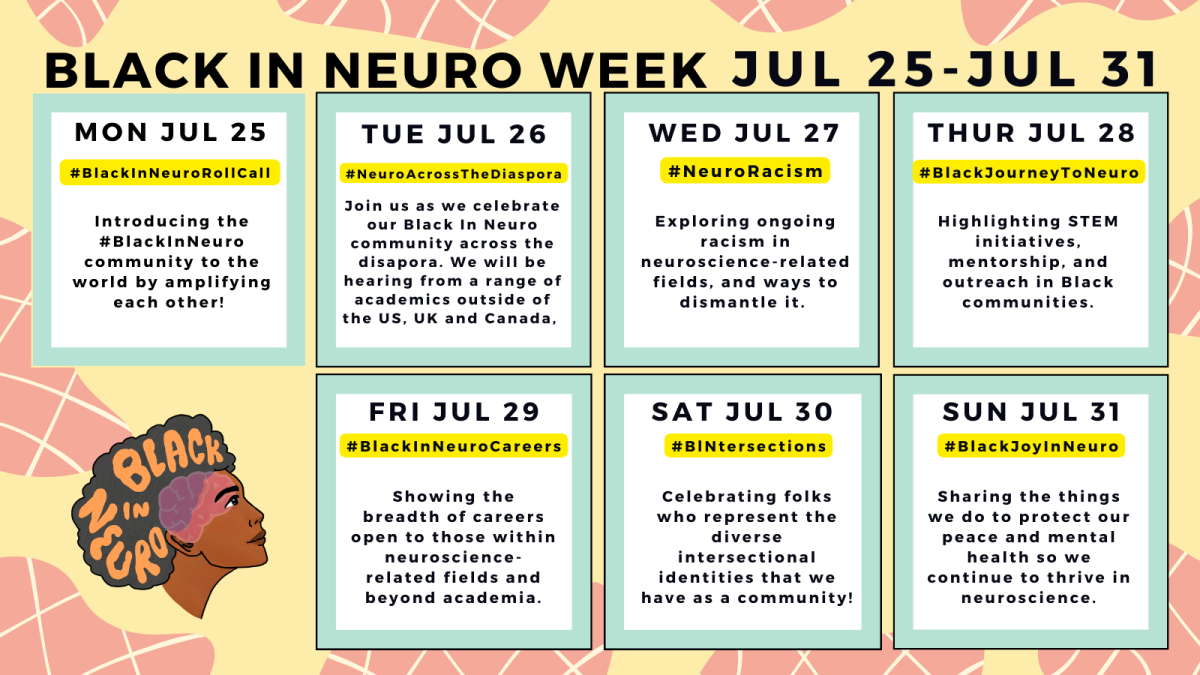

Since then, Ferguson has excelled not only in top-tier science, but also in the kind of activism and advocacy she hopes can improve the diversity and culture of the scientific community around her. In 2020, she helped found the organization Black in Neuro and worked with her co-organizers to host two years in a row of well-attended virtual Black in Neuro weeks.

Meanwhile, Ferguson was listed on the 2021 Forbes list of 30 scientists under 30 for her work studying parvalbumin interneurons (PVINs), a specialized brain cell whose dysfunction is thought to be involved in schizophrenia, autism, epilepsy and other neurological conditions. She’s currently a postdoc in the lab of John Huguenard at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University, where she’s been examining how PVINs influence the ability to pay attention in a rare disorder called absence epilepsy. At the start of 2023, Ferguson will be opening her own lab as an Assistant Professor in Genetics and Neurology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital. There she will expand her work studying cognitive function in mice with mutations linked to neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders with an aim toward identifying biomarkers and directing therapeutic development.

Just in time for Black in Neuro Week 2022 (#BINW22), we caught up with Ferguson about her research at Stanford, her passion for activism, and her thoughts on juggling both.

What is absence epilepsy and how does it relate to the work you did prior to coming to Stanford?

Most people associate epilepsy with convulsive seizures that are obvious and apparent. In absence epilepsy, though, patients have frequent, brief periods of unconsciousness that can even go unnoticed—sometimes as many as 100 per day. These seizures typically happen in periods of quiet waking, without loss of muscle tone—meaning patients don’t collapse—and often last only a few seconds. Although these seizures can occur with fluttering of the eyelids or repetitive movements of the face or hands, they can sometimes be barely detectable, both to observers and to patients themselves. But during these brief blips of unconsciousness a patient can’t take in information, meaning it’s incredibly disruptive for many aspects of life, like trying to learn in a classroom or get through a meeting at work.

Recently, experts have started to realize that attentional deficits in this condition go beyond just these periods of seizure. Even in patients where seizures stop completely, either because of drug treatments or a [young] patient growing out of seizures, really impactful attentional and other behavioral challenges can persist. But we don’t really know why.

My graduate work looked at how drops in activity of parvalbumin interneurons can negatively affect attention. I came to John Huguenard’s lab at Stanford to study this further in a mouse model of absence epilepsy.

Tell me more about these parvalbumin interneurons (PVINs). What exactly are they and how do they affect attention?

PVINs are inhibitory cells, which means they function to reduce the activity of other cells in the brain. The kind I study are described as basket cells because they send out processes that look as if they are cupping the cell bodies of other neurons, and it’s through these processes that they exert their activity-dampening effects. In absence seizures and other epilepsies we think that PVINs and other inhibitory cells get sluggish, letting the cells they should be regulating become overactive, which then leads to seizures and other negative consequences.

Our recent preprint, which we are working on putting through peer review, explores how PVINs might contribute to some of the attentional issues seen in absence epilepsy in mice. I hope that someday we might be able to suggest drug treatments for such attentional deficits, which at this point don’t exist.

You’re not just a scientist; you’re also an activist. How did you decide you wanted advocacy and activism to be a focus of your work as well? And how did that lead you to get involved in Black in Neuro?

By early- to mid-grad school, I had started to identify some major gaps in my research environment that I felt could be improved. One of the big things was that I didn’t have examples of people in positions of power that looked like me. There was a big lack of representation. I started to get involved in groups where I thought I could work to create more resources for minoritized scientists and improve diversity in my community. As a graduate student at Drexel University in Philadelphia, I served as vice-president of the Biomedical Graduate Minority Association and then became president of the Graduate Student Association. Then at Stanford I continued similar work and became the co-president of the Stanford Black Postdoc Association.

Black in Neuro was one of the early “Black in X” initiatives to come out of the summer of 2020, a response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and other acts of racism against Black people just trying to go about their daily lives. When our co-founder and now president, Angeline Dukes, tweeted at the time asking when our field would have a Black in Neuro week, I was one of about two dozen people who immediately wanted to get involved.

And you’ve continued to work with Black in Neuro, now as its Director of Programming. What are some of your favorite things about the organization?

I think all of us on the team have previously been frustrated by the inability to really move forward tangibly on the things we're most excited about, particularly when working within institutional boundaries. When we created Black in Neuro as our own organization it meant we could make our own rules, and move at our own speed, instead of just explaining the problems without much ability to take action. In the last two-and-a-half years, keeping with our core tenets of building community, providing resources and increasing visibility, Black in Neuro has put Black scientists on what is now an international stage and allowed them to speak about whatever’s in their hearts. Sometimes that’s their science and sometimes it’s their perspectives on diversity — whatever they find most important to them and their journey. So far, (not counting this week’s BINW22) we’ve put on over 80 events with more than 10,000 participant engagements. This year we became a 501(c)(3), meaning we’re an official nonprofit organization. It just shows that If you have a group of excited and motivated people working on their own terms, there's really nothing you can't do.

Sounds like you’re doing a lot of wonderful things, but I’m sure that also means a lot of work on top of being a full-time researcher. How do you balance top-tier science with social activism within the scientific community?

I'm still figuring it out. It’s important to recognize that we're not just scientists—we're also individuals that have other interests and needs. I think it’s been important for me to accept that I cannot give my 100 percent to both at the same time. When one picks up, the other is going to slow down, and I’ve tried to be intentional about putting myself in situations and environments that are supportive of that.

Are there aspects of your Stanford team or the Wu Tsai Neuro community that have been helpful in doing that?

I’ve been really lucky to have mentors that have been supportive of the work I do outside the lab. John [Huguenard] in particular has really given me the space to get my work done in a way that works for me so that I can do both.

Wu Tsai Neuro also has the Committee on Diversity, Inclusion, Belonging, Equity and Justice, which I’m not involved in, but has made a really tremendous effort in the last few years to center the voices of minority scientists and provide funding and resources for them to put on some great programming.

Minority researchers often face a twofold hit by being impacted both by additional systemic obstacles and the expectation to be the ones putting time and energy into addressing those obstacles. What is your advice to younger or earlier career researchers about determining their own roles in the intersection of these spaces?

I would let them know that there's no perfect formula and that it will look different for everyone. Even just by existing in spaces that were not traditionally designed for them, they’re already doing so much to move the field forward. Not everyone will want to do explicit activism work, and no one should feel obligated to just because they are a person of color, diverse or minoritized in any way.

But I think another part of the equation is that, as a field, we also need to be thinking about how to shift our incentive structures so that minority scientists who want to get involved in diversity concerns don’t feel like they have to take on twice as much. When people are up for tenure we should want activism and advocacy work—not just papers and grants—to be weighted heavily in that decision.

For anyone who does get involved it’s important to recognize that you’re not going to dismantle the entire system on your own. So many of these problems are systemic and have existed since the beginning of science. No one should place too much pressure just on themself. We need to be putting pressure on institutions to take up some of the labor disproportionately placed on minorities and change those incentive structures to reward that kind of work.

In your mind, are allies an important part of taking some of that pressure off?

There are definitely examples of allies doing really wonderful work in this space. What comes to mind for me is all of the allies on the Black in Neuro team. We have several organizers that are not Black, and they have been a critical part of the backbone of the team. In a lot of ways they’ve stepped in and stepped up just as much as our Black organizers, but have always made sure to center our needs and voices. What can sometimes happen when allies are doing the work is that they're not making sure to center those minoritized voices. Our organizers, though, have just gone above and beyond to be there and put in the work while keeping the focus on our experiences.

We're just starting Black in Neuro Week 2022. What should we be sure not to miss?

I mean, the whole week [laughter]. I'm biased, but I think every day has something good! For example we'll talk again about “neuro-racism” and how a lack of representation of Black people in science has led to under-diagnosis and misdiagnosis. We’ve added a new theme of “Black in Neuro across the diaspora” where we’ll talk about reality for Black scientists internationally, not just in the United States, UK, or Canada. We’re also highlighting stories from HBCU graduates, with a panel where HBCU graduates will talk about their paths into the field. Historically Black colleges and universities are places that have a ton of incredible young scientists and young minds, but a staggeringly low amount of neuroscience programs, something we hope will change. We’ll have lots of great stuff — not to be missed!

The Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute is a proud sponsor of Black in Neuro Week 2022.

Image courtesy Black in Neuro.