Q&A: How wearable tech can teach and heal with the power of touch

Part of our Next-Generation Neuroscience series

Caitlyn Seim considered herself a technologist from a young age. Growing up with a mom who was once a mechanic meant that tinkering, for Seim, was just part of being a kid. So when she enrolled as a Georgia Institute of Technology undergraduate student at just 15 years old, electrical engineering seemed like the natural choice. By the time she finished her undergraduate studies, she was determined to create tech that could solve real, human problems.

As a PhD student at Georgia Tech, Seim developed gloves that could “teach” the body using electrically generated vibrations, without the need for users to pay focused attention to what they were learning. Shortly after, a weatherman on CNN demonstrated to his audience how the gloves had bestowed him with the ability to play the first notes of Ode to Joy on the piano, simply by stimulating the corresponding fingers as he went about forecasting the weather. Seim's wearable technology inventions also caught the attention of the U.S. Air Force when she and colleagues applied the technique to learning Morse Code. The team also showed that they could teach the braille alphabet in a matter of hours using a similar approach, an approach that might one day help address the braille literacy crisis in the United States.

Since then, Seim has been determined to unlock the potential for wearable haptic devices — devices that stimulate the sense of touch — in healthcare. During her PhD, she began working to see if her gloves might help people who’d suffered brain injury regain some of the basic movements and sensation they’d lost, with promising results. In 2019 she won a Neuroscience:Translate Award from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and moved her research to Stanford, where she works with Allison Okamura in the Collaborative Haptics and Robotics in Medicine (CHARM) Lab and Maarten Lansberg in the Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences to applying her technology to reduce symptoms of stroke affecting the upper and lower limbs. In 2021, she won a Wu Tsai Neuro Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Scholar Award to continue this work.

The Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Interdisciplinary Scholar Awards provide funding to extraordinary postdoctoral scientists at Stanford University engaging in highly interdisciplinary research in the neurosciences.

Learn more >>

We spoke with Seim to learn more about what she’s up to now:

Let’s start with your gloves: How could the same device that teaches you to play the piano help someone recover from stroke?

The glove we created applies vibrotactile stimulation, which is essentially, non-invasive vibrations applied to the skin. This form of input worked well in learning things like playing the piano or typing braille because unlike written or verbal instruction, haptic input communicates directly with the body. Your body is listening to what's coming from the device in a way that allows the technology to convey instructional cues to your muscles or other body parts. That can be very beneficial for motor learning, even without your conscious effort, because if you wear the glove, for example, for a long time you can apply a lot of repetitions without strenuous attention.

Today I perform clinical research on new wearable stimulation devices to improve limb function after stroke. A lot of my current work is in patients with spastic hypertonia (often just called “spasticity”), which is a very common symptom of brain injury that results in involuntary muscle contractions that distort limbs and limit range of motion. It really disrupts hand use for a lot of people. There is the potential for this same type of glove to improve hand function, because we believe the intensive stimulation can inhibit the overactive motoneurons in the limb that drive spasticity. Ultimately, we are designing a neuromodulatory treatment.

This kind of stimulation also mimics the sensory feedback you get from exercise or normal movements, but to an enhanced degree. Sensory feedback is thought to be a big reason why rehabilitative exercises are so important. For the 50 percent of stroke survivors who can't exercise effectively because they have moderate-to-severe effects of brain injury, wearable stimulation devices can provide input to the brain to reactivate or strengthen still-existing connections, potentially helping patients regain some control they’ve lost over the limb.

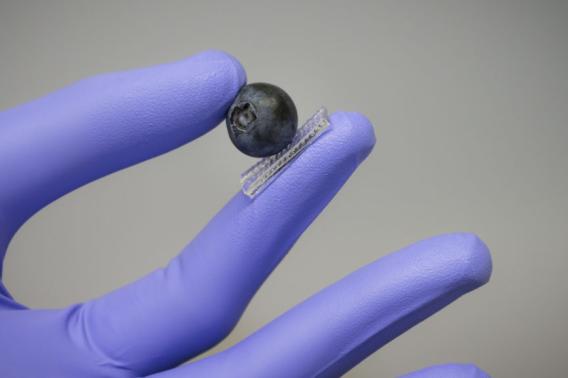

Seim is conducting a clinical trial to evaluate how well the wearable technologies she and her team has designed can improve mobility in stroke survivors. Image credit: Andrew Broadhead

And what are the ultimate goals of this work? If everything went your way for the next decade or so, what would you like to see come out of this research?

Well spastic hypertonia can have a huge impact on people’s lives. It can make someone unable to open their hand, for example, or pick something up. Right now, the gold standard for treatment is Botox injections into the overactive muscles, which essentially weaken those muscles — not good when you’re trying to use your hand more. Unfortunately, notable effects of Botox also only last about two or three weeks for each injection.

With my clinical study I want to determine whether wearable vibrotactile stimulation might be an alternative treatment to Botox or something that could be used alongside it. If this method proves as powerful as we hope, I would love to be able to make it available to individuals with brain injury in the form of a device covered by insurance.

I’m also just very passionate about continuing to work on wearable haptic devices that can send messages to the body. I think there are incredible strides that can be made in both the average healthy person and in rehabilitation with this approach.

I imagine there are endless possibilities. You and your colleagues recently wrote about some in a paper about “computer-human integration,” and you’ve also spoken quite a bit about “human augmentation.” For people who don’t know about this field, those terms might make them start daydreaming about getting new superpowers or conjure images from the last sci-fi film they saw. But what are we really talking about?

People can think sci-fi if they want — in a way that’s what we’re talking about. We are talking about the many ways that devices can become more integrated with the human body. But you can recognize that without getting too unrealistic.

The fact is that we’re already augmenting our brains through technology. For example, my knowledge doesn’t end at what I store in my brain — I have all of the internet to also act as an external store of knowledge. That’s an example of us amplifying our abilities as we get more closely coupled with our technology.

But I don't really like to get too silly with these things, because I think there are a lot of people who approach human augmentation in a silly way, without realistic technological methods. And that taints the field. This isn’t about giving us superpowers, it's about discovering new forms of technology that can truly communicate with the human body to drive realistic and tangible positive influence.

Seim and colleagues design wearable technology that people with low mobility can put on easily and wear with comfort. Image credit: Andrew Broadhead

What are some examples of the technology you do respect and think are perhaps realistic?

There are some great examples of really good things people are doing in medicine besides projects I’m directly involved in. For example, there’s been some really interesting research around how we might address irregular heartbeats by stimulating the vagus nerve, which brings signals from the brain to the heart. And Zhenan Bao is doing a lot of really great stuff here at Stanford working on bandages that provide electrical stimulation to help heal wounds. Allison Okamura, one of my mentors, is also working on robotic needle steering, a form of robotics that allows surgeons to augment their abilities to make surgeries more precise.

So I do prefer to stay focused on these more serious, tangible things because we’re not working with magic here. We’re working with mechanics, electronics, and chemistry and we’re working with them to solve real problems.

How has your support from Wu Tsai Neuro's Interdisciplinary Scholar award and Neuroscience:Translate grant helped you tackle these real-world problems?

These programs let me work with a lot of different people in an interdisciplinary manner that I really enjoy. Wu Tsai Neuro feels like a community that I can rely on — having relationships with faculty and staff in the institute really empowers me.

I'm also part of the Stroke Recovery Team, which is connected to Stanford Hospital and the School of Medicine, giving me an important window into the needs of patients. I work frequently with clinicians and physical therapists who are on the ground, treating patients with the conditions I’m studying. I can talk to them about which muscles they typically see acting up and get their opinions on strategies for improving range of motion for example.

The School of Engineering and the Department of Mechanical Engineering are also absolutely essential resources that include prototyping spaces and are particularly modern and design oriented. Stanford’s mechanical engineering department has an understanding for tangible design and prototyping, which is essential if you're going to be making a new physical technology for people to use. Lots of other mechanical engineering departments are more theoretical and don’t have as much of a sense for the need to build and iterate as a fundamental approach for real world development.

That all seems really important for working with patients, which comes with a lot of responsibility. How do you approach working with your participants?

The design and administration of our studies is a very careful process that involves input from a number of sources, including all the collaborators I just mentioned. But a very key part of that process is also communication with patients. I believe in listening to the wants and needs of these individuals, and truly knowing how their differences impact all aspects of their lives. There’s a lot of hope in rehab — I love that. But part of that comes from a respectful and conscientious process, so it’s important for me to be mindful of the power I have as an advocate and to make sure I’m understanding participants' needs completely and accurately.

Seim evaluates the grip strength in a clinical trial subject who has been using her wearable technology. Image credit: Andrew Broadhead