Q&A: Studying how the brain controls natural movements just got easier

Controlling movement is one of the brain’s core functions — and also one of its most complex. To accomplish even the simplest of tasks, like picking up a glass of water, your neural circuits must precisely coordinate dozens of muscles in perfect synchrony.

Neuroscientists have made progress in understanding how the brain accomplishes this task by dramatically simplifying the movements they study. By making detailed recordings of brain activity while an animal moves an arm in a carefully prescribed manner, they can glean principles underlying the function of the brain’s movement control circuits — which reside in the so-called motor cortex, a strip of brain tissue that stretches from ear to ear like a headphone band.

But in the real world, movement is never so simple. Natural movements can involve hundreds of muscles across the whole body, and are often unique and unstructured — making them a challenge to study with standard experimental protocols.

Now, a team affiliated with the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford has developed custom technology that can capture all the complexity of naturalistic animal behavior and synchronize it with wireless recordings of brain activity.

A video abstract describes the new behavioral imaging and brain recording platform. Credit: Michael Silvernagel and Alissa Ling, the Brain Interfacing Laboratory.

The project, described in an article published September 8, 2021 in Science Robotics, was co-led by electrical engineering graduate students Michael Silvernagel and Alissa Ling, both of whom are members of the Wu Tsai Neuro Center for Mind, Brain, Computation, and Technology (MBCT).

Ling and Silvernagel performed the research in the Stanford Brain Interfacing Laboratory, directed by Paul Nuyujukian, MD, PhD, a Wu Tsai Neuro member and assistant professor in the departments of Bioengineering and Neurosurgery.

The team used 3d camera technology adapted from the growing self-driving car industry to track an animal’s every movement — from walking to grooming to trying to catch a fly. The platform synchronizes these so-called “kinematics” with wireless recordings of brain activity from the motor cortex, allowing the researchers to study for the first time the details of how the brain controls complex, natural movements.

Silvernagel and Ling shared their thoughts on how their new platform could advance the study of movement neuroscience:

Silvernagel is an MBCT student member and Ting is an MBCT MBCT NeuroTech Trainee at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

What was the question that motivated your research?

Silvernagel: The question we're trying to answer is what goes on in the brain that allows us to move as we do? If we understand this question, we can make better assistive devices that read signals from the brain to restore movement to those who are paralyzed or guide therapies for those who have suffered brain injuries like stroke.

A traditional experiment in our field consists of a macaque, sitting as I am now, using one arm to perform a task such as reaching for targets on the screen. Movement kinematics of the arm are recorded and synchronized to neural data. These studies have been instrumental in furthering our knowledge of how the brain controls movement, but they are also somewhat contrived in that they don't capture how animals would naturally move.

Ling: To answer how the brain controls naturalistic movement, we have to conduct studies in a fully unconstrained environment, which allows a greater range of motion. Currently, there are very few platforms that can capture free behavior with synchronized neural data. So we developed our own.

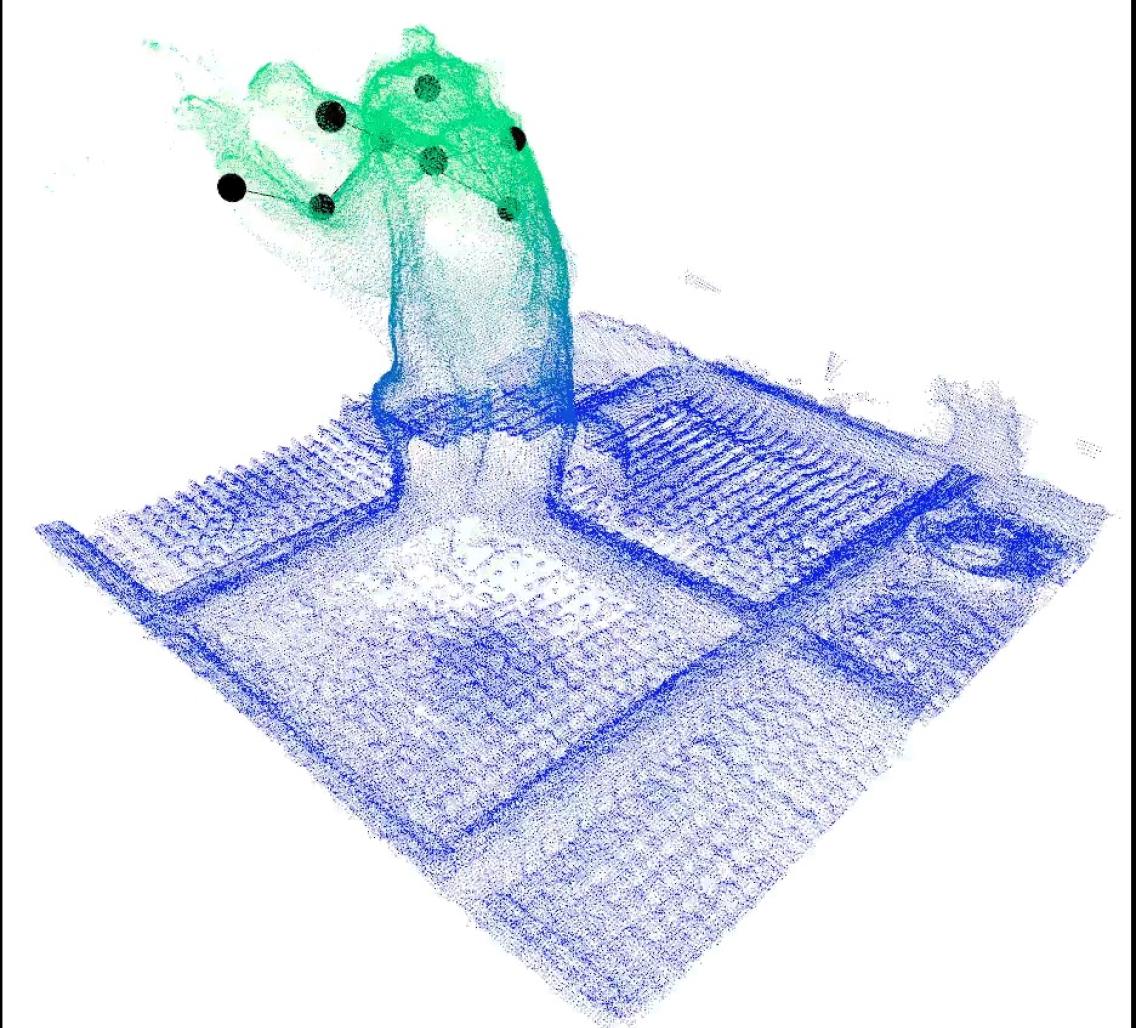

Silvernagel: The platform we present in this paper uses depth cameras that recreate a three-dimensional representation of the experimental environment in which our animal resides. We can reconstruct movement kinematics of the animal without using any markers, allowing it to move in a more naturalistic way. Our platform also allows for the synchronous recording of wirelessly transmitted neural data, which lets us study how the brain controls movement as the animal performs a task as it naturally would.

What motivates you personally about this work?

Ling: My goal is to help people with motor disabilities regain mobility and function through developing brain controlled robotic prosthetics. I am especially interested in prosthetics that help people walk again, because I believe that the ability to walk gives people the most freedom. I first discovered my interest at Walter Reed Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, where I got to see cutting-edge technologies, such as a brain-controlled prosthetic arm, or a robotic exoskeleton that helped wounded soldiers regain their ability to move again. I wanted to explore the possibilities of these devices, giving them an even greater return to normal function.

Silvernagel: My initial interest in the brain and assistive devices reaches back to when my aunt was diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration, which is a degenerative disease that affects areas of the brain that deal with movement. It was heartbreaking to see someone so smart and so vibrant gradually lose her ability to move and go about her daily life. Towards the end of her life, to communicate with her, we had a printed out keyboard and we would scan our fingers across different letters, waiting for her to move her eyes or to blink. I could tell that she so badly wanted to engage and communicate with us, and she just couldn't.

Another formative experience came after my sophomore year of undergrad, when I spent the summer working at a school for children with disabilities in southern India. That experience reaffirmed just how fortunate I am and how many people in the world are in great need. When I began graduate studies, I knew that I wanted to leverage my talents as an engineer to better the lives of others.

How do you hope this study will impact the field?

Silvernagel: I hope that the motor systems neuroscience community is excited about our platform, because it has the potential to shift how we think about designing studies. In the past, a lot of consideration had to be given to ensure that the animal didn't interfere with electronics that either recorded movement or recorded neural data. With our platform, this isn't really a concern anymore. The platform is also composed of mostly low-cost commercial components and this helps reduce the barrier to entry if other groups want to replicate our setup and perform their own experiments, which is something I hope happens in the future.

Ling: I think our work can be interesting to a lot of different people — not just others in our field, but athletes, and individuals with motor disabilities as well. With our platform, we can discover how the brain controls many different types of free behavior and learn things such as naturalistic motor skill development and how the brain recovers from injury. This information may result in improving therapies for people with motor disabilities.

What are you most excited about in this work?

Ling: I am really excited about the diversity of movement that we can explore with this platform, ranging from walking to running, jumping and climbing. We can make a whole range of brain machine interfaces for all of these different types of movements, and this can help us get closer to creating a device that returns a patient back to normal function.

Silvernagel: For me, the most exciting aspect of this platform is that it's highly flexible and reconfigurable. We're only limited by our own creativity. One of the reasons I love this work is that we get to come in every day and flex those creative muscles to solve really difficult problems.

The ability to create tasks that vary widely in the cognitive difficulty and the types of movements required while recording kinematics from across the entire body will allow us to generate really rich and diverse data sets. These data sets will then hopefully broaden our understanding of the brain, and hopefully lead to better assistive devices to restore movement or help guide rehabilitation therapies for those who have suffered from brain injuries.