By Amy Adams

Academics is often a visual pursuit – reading journal articles, examining manuscripts, looking through a microscope. But some things can only be learned through sound. The boom of volcanoes, buzz of mosquito wings or tone of a person’s voice all convey information lost to a visual observer. The challenge in all of these is learning how to make sense of the sounds around us, in some cases with technology and in others by simply listening to one another more carefully.

Beyond helping us interact with the world and with each other, sound can be an almost physical tool. Frequencies beyond the range of human hearing can wake up sleeping appliances and arrange heart cells in the lab. Sound waves can even be a means of peering into the body and diagnosing health conditions.

Stanford scholars from across medicine, engineering, social sciences and the arts are working together to interpret and manipulate this audible world, and to restore hearing to those whose ability is diminished. They’re even helping people learn to listen more carefully to each other.

Listening to climate change

Chris Chafe, director of the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, composed the piece of music based on the global average temperature and CO2 from A.D. 850 to 2016 – data compiled by his colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley.

As temperatures rise and CO2 levels increase, the music goes from a low hum to an increasingly frenetic whine. What people might not see day to day becomes hard to ignore through sound.

Sound learning

The world is filled with pinging, buzzing, reverberating sounds that carry information. Rumblings that portend a volcano; underground vibrations elephants use to communicate; jet plane noises that, if quieted, could also improve power production from wind farms. This is some of the work underway at Stanford in which researchers are probing the world by listening:

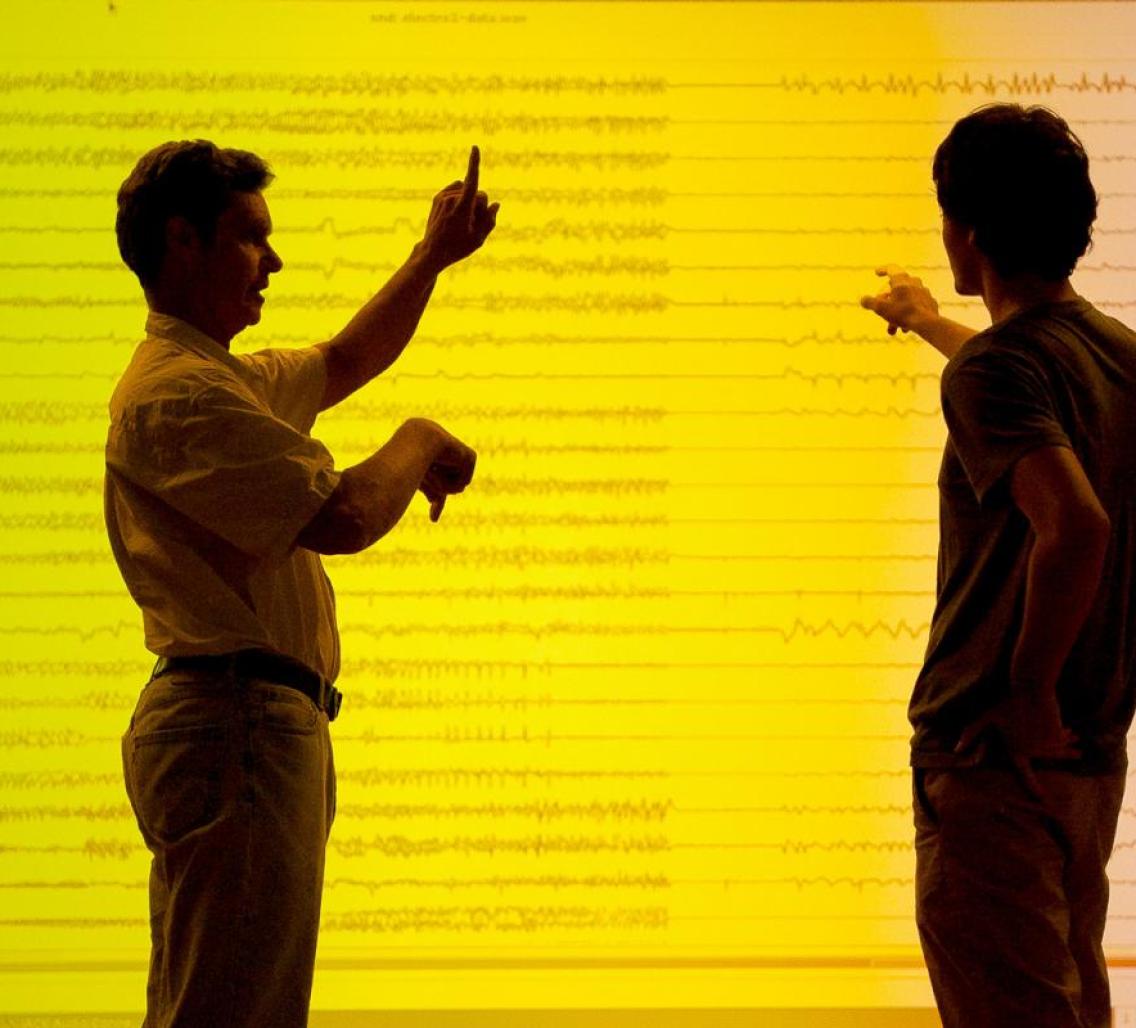

Science & TechnologyBrain stethoscope listens for silent seizuresBy converting brain waves into sound, even non-specialists can detect “silent seizures” – epileptic seizures without the convulsions most of us expect. |

|

Science & TechnologyStanford scientists eavesdrop on volcanic rumblings to forecast eruptionsSound waves generated by burbling lakes of lava atop some volcanoes could provide advance warning to people who live near active volcanoes. |

How modeling air turbulence can improve wind farm performanceTechniques for making fast-flying aircraft quieter could pay off with higher power output from wind farms. |

|

Caller ID in the wild: Elephants hear undergroundIn the vast expanse of African grasslands, wild herds of migrating elephants have learned to communicate with each other by listening with their feet to vibrations in the ground. |

Earthquake acoustics can indicate if a massive tsunami is imminentAcoustic characteristics of the 2011 Japan earthquake indicated that it would cause a large tsunami. The technique could be applied worldwide to create an early warning system for massive tsunamis. |

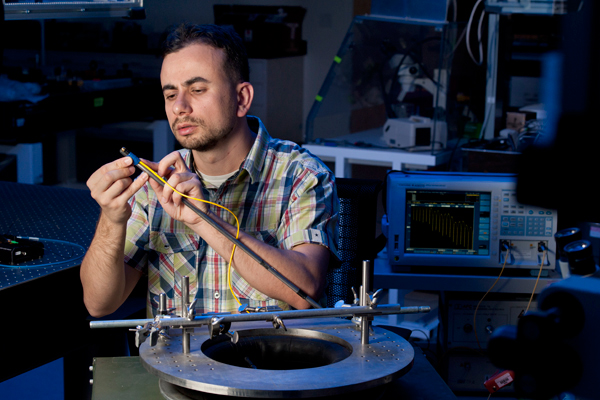

‘Orca ears’ inspire Stanford researchers to develop ultrasensitive undersea microphoneA powerful hydrophone based on ears of orcas could help researchers studying everything from whale migration to fisheries populations. |

Sounds of the seaStudents in Music 220A build and test hydrophones to capture whale and marine sounds, in addition to learning techniques for digital sound synthesis, analysis, effects and reverberation. |

Mapping mosquitoes by their buzz

It’s a sound that can keep even the weariest from falling asleep: the high-pitched whine of a mosquito. This irritating buzz already makes people run, slap and slather on repellent. But if bioengineer Manu Prakash has his way, it may also prompt people to take out their cellphones and do a little science.

A new cellphone app called Abuzz not only identifies the species but puts it on a map. The resulting distribution can help scientists track mosquitoes that carry diseases like malaria, yellow fever, dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya and Zika.

Here’s the sound of Aedes TK mosquitoes in the Prakash lab.

Sound tools

Invisible sound waves carry a physical force. They rattle against inner ear cells to create the sensation of sound, and similar waves can trigger devices to turn on, detect hidden tumors or even probe the seafloor. These waves hold power well beyond what we can hear.

|

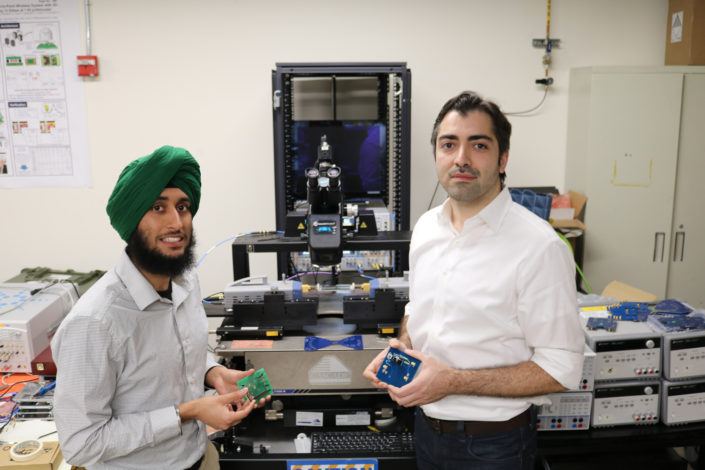

Science & TechnologyNew method for waking up devicesA device that’s turned off doesn’t suck battery life, but it also doesn’t work. Now a low-power system that’s always on the alert can turn devices on when they are needed, saving energy in the networked internet of things. |

Science & TechnologyStanford scientists use ocean waves to monitor oil and gas fieldsNew technique exploits naturally occurring seismic waves to probe seafloor at less expense, and with fewer ill effects on marine life caused by air guns in use today. |

Science & TechnologyNew ‘tricorder’ technology might be able to ‘hear’ tumors growingA new technology has promise to safely find buried plastic explosives and maybe even spot fast-growing tumors. The technique involves the clever interplay of microwaves and ultrasound to develop a detector like the Star Trek tricorder. |

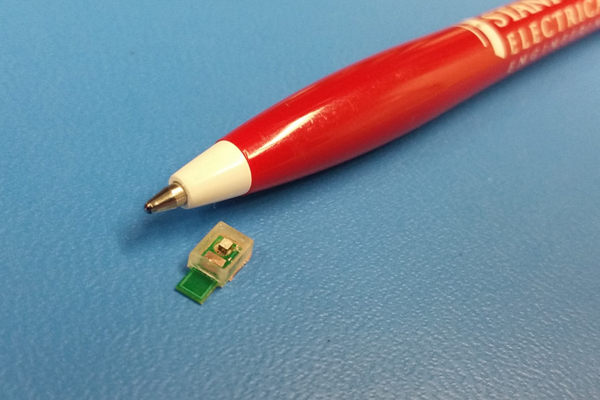

Stanford engineers develop tiny, sound-powered chip to serve as medical deviceUsing ultrasound to deliver power wirelessly, Stanford researchers are working on a new generation of medical devices that would be planted deep inside the body to monitor illness, deliver therapies and relieve pain. |

|

Ultrasound and microbubbles flag malignant cancer in humansA Stanford-led team of researchers has developed tiny bubbles that bind to malignant tumors, making them visible to ultrasound imaging. |

Social media listenersAcross the vastness of the internet, there are countless disease support groups where ill people share questions, advice and hope. In some cases, these online conversations could reveal unreported adverse reactions to approved drugs. |

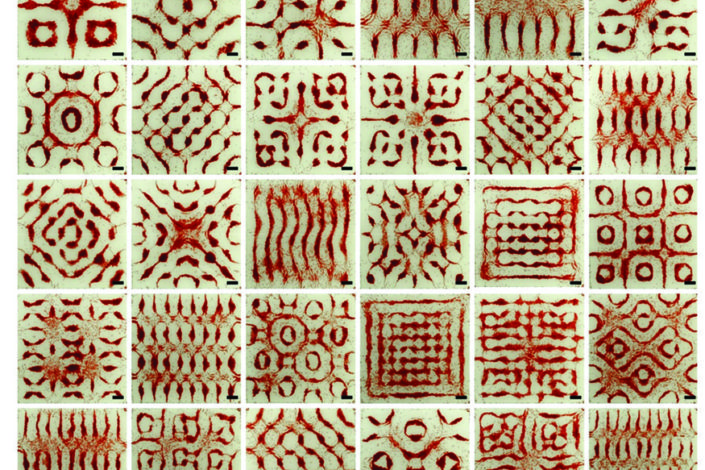

Acoustic choreographySound waves can nudge heart cells in a lab dish into any configuration, including packing them densely to mimic the human heart. |

Ultrasound solutionA new type of ultrasound can shrink tumors in kids. |

Gendered listening

Whether or not one person interrupted another depends on whom you ask. Male listeners are more likely to view women who interrupt another speaker in an audio clip as ruder, less friendly and less intelligent than men who interrupted. Female listeners do not show a significant bias in favor of female or male speakers.

Katherine Hilton, who conducted the research as a graduate student at Stanford, knew other studies had shown that women tend to be seen more negatively than men if they speak up or interrupt. She developed a set of audio clips of men and women interrupting and played them to 5,000 Americans, who then rated the clips by whether the speakers seemed friendly and engaged, listening to one another or trying to interrupt.

Here are a few of the clips that were most polarizing:

Understanding through listening

It’s one thing to hear and another to listen. The act of listening and communicating can help ease troubled relationships, steer medical decisions and even bring the past to life. But it’s not always easy, which is why some researchers are trying to unravel how we listen and why it’s so important.

|

Social SciencesStanford scholars discuss mental health and technologyConversational software programs might provide patients a less risky environment for discussing mental health, but they come with some risks to privacy or accuracy. Stanford scholars discuss the pros and cons of this trend. |

Music and the mindFamed lyric soprano Renée Fleming talks about the left-brain/right-brain initiative, which she launched with NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, and about the connection between medicine and music. |

Are you listening?Modern medicine challenges the crucial bond between doctors and patients. |

Arts & CreativityStanford musicologist brings the 15th century to lifeStanford’s Jesse Rodin reanimates musical experiences of the distant past through performance. |

|

Can your personality explain your iTunes playlist?Researchers find a new way to examine your musical taste, with implications for the music and health care industries. |

Mom’s voice activates many different regions in children’s brainsA far wider swath of brain areas is activated when children hear their mothers than when they hear other voices, and this brain response predicts a child’s social communication ability. |

5 Questions: Ombudsperson Jim Laflin on the importance of listeningJim Laflin, the “listener” for the School of Medicine, said in an interview that rather than advise people on what to do, he helps them to clarify and identify their options. |

A relationship built on trustOne patient says a strong relationship with her doctor was crucial in finding success. |

|

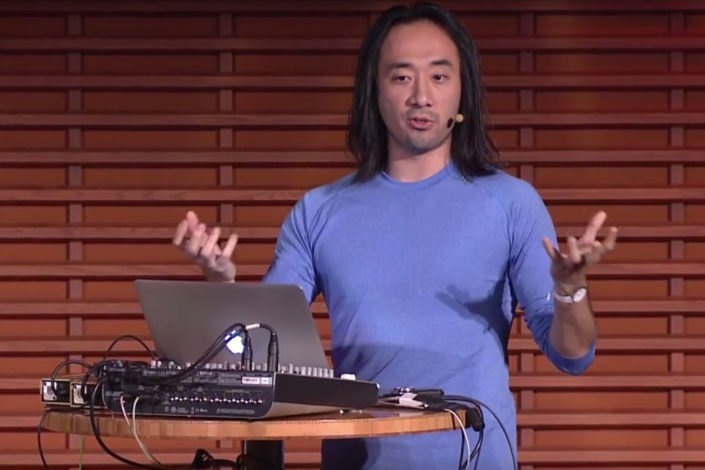

This is computer music: Ge Wang at TEDxStanfordMusic made by laptops, smartphones and other technologies isn’t about the tech or even the music – it’s about understanding people. |

Volcanic screams

In 2009, Mount Redoubt, a volcano outside Anchorage, Alaska, began spewing towering ash plumes more than 12 miles tall. Before it did so, a sequence of tiny earthquakes emanated from the volcano’s innards. Though inaudible to listeners on the surface, sensitive seismic instruments placed along the active volcano’s slopes picked up the vibrations.

Sped up 60 times their original speed, the recording’s pop, pop, popping accelerated into what Alaskan seismologists working with Stanford geophysicist Eric Dunham nicknamed “the scream.” Then, a brief silence before “Boom!” An explosion.

The recordings prompted the team to create a model of what led up to the volcano’s explosion, which could help predict future eruptions.

Restoring sound

Some people are born without the ability to hear, and adults older than 70 are more likely to have hearing loss than to have normal, healthy hearing. For those seeking help, better diagnosis and treatments are on the horizon both through improved technology and the possibility of one day regrowing damaged inner ear cells.

|

To hear againBirds regrow damaged inner ear cells. Why can’t we? The solution may lie in stem cells that can mature into functioning inner ear cells. |

A toxic lifesaver, reconstructedA commonly prescribed antibiotic can also cause hearing loss. “If we can eventually prevent people from going deaf from taking these antibiotics, in my mind, we will be successful,” says otolaryngologist Tony Ricci. |

Hear and nowAbout two-thirds of adults over 70 have hearing loss, including Edwin Lutz, who takes less pleasure in being outside without the ability to hear nature’s sounds. New diagnoses and treatments in the works could help. |

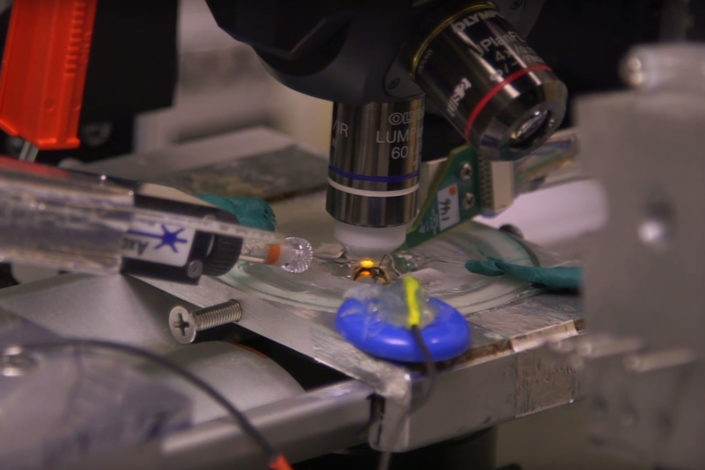

Stanford-developed probe aids study of hearingBy measuring minuscule forces within the inner ear, scientists are learning more about how humans hear. |

|

Stanford hearing study upends 30-year-old belief on how humans perceive soundA new study from Stanford otolaryngologists upends the way scientists think about how we hear – and the findings could fundamentally change the way doctors treat hearing loss. |

‘What’s that?’ Identifying cells important to hearing lossStanford researcher and otolaryngologist Alan Cheng and colleagues have found the cells that mature into the hair cells responsible for detecting sound. This discovery could help restore those cells after hearing loss. |

Stanford scientist looks for a deeper understanding of hearing through the bones in our headsStanford mechanical engineer Sunil Puria is unraveling the mysteries of bone conduction hearing, which could lead to a better understanding of hearing – and some types of hearing loss. |

Battling hearing loss on and off the battlefieldThe loud blasts from improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, in war zones is causing an uptick in hearing loss among soldiers, but it turns out some of the damage is reversible. |