The neural switch that keeps us grounded as we daydream

Thousands of times a day, your brain switches back and forth between engaging with the external environment — gathering sensory information or forming new memories — and turning inward to focus on the internal landscape of thoughts and reflections on the past and future.

“Sitting in an armchair on a quiet Sunday afternoon, you may be thinking about how you wandered around on a beach or city on your vacation last summer. This is mind wandering, daydreaming. But then when your cat jumps off from the table and makes a sudden noise, you instantly get back to the present and know where you are at that moment,” explained Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute affiliate Ivan Soltesz, the James R. Doty Professor of Neurosurgery and Neurosciences.

Scientists like Soltesz have long wondered how this neurological switch between “online” and “offline” processing works and what controls it.

New research led by Wu Tsai Neuro Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Scholar Ernie Hwaun and colleagues in the Soltesz lab suggests the key may be in specific patterns of neural activity within the hippocampus, a brain region critical for memory and navigation.

The research was published March 13, 2024, in Nature, and was led by Hwaun and then-postdoc Jordan Farrell, who is now a faculty member in neurology at Harvard Medical School, with assistance from former Soltesz lab postdoc Barna Dudok.

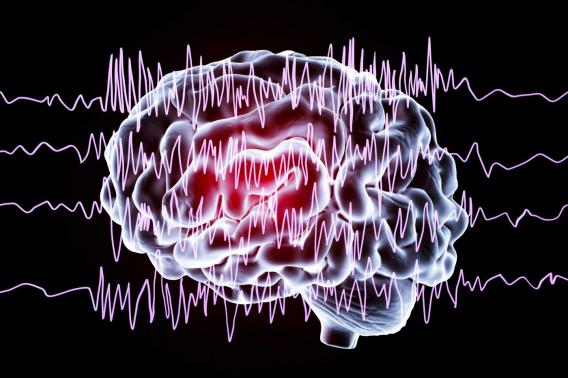

The new study zeroed in on two types of electrical events produced by networks of neurons in the hippocampus: sharp wave ripples and dentate spikes.

Sharp wave ripples occur when the brain is in internally focused, daydream-like states and are widely known to be involved in neuronal replay of past experience, crucial for consolidating memories and planning. Altered sharp wave ripples have been implicated in several major neurological and psychiatric disorders, including temporal lobe epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, little is known about the function of dentate spikes, despite their frequent occurrence in between sharp wave ripples.

Hwaun and colleagues have now discovered that dentate spikes seem to be connected with a unique brain state involving heightened activity across the brain, especially in higher-order networks that process complex information. These spikes are linked to brief moments of arousal from the "offline" state, suggesting a mechanism by which the brain can momentarily re-engage with the external world during otherwise introspective states.

Specifically, the researchers found that during dentate spikes, the hippocampus encodes the individual's current location in space, indicating active processing of external sensory information, in contrast to the internal memory replay seen during sharp wave ripples.

“Sitting in an armchair on a quiet Sunday afternoon, you may be thinking about how you wandered around on a beach or city on your vacation last summer. This is mind wandering, daydreaming. But then when your cat jumps off from the table and makes a sudden noise, you instantly get back to the present and know where you are at that moment.”

— Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute affiliate Ivan Soltesz

“One of the most surprising findings about dentate spikes is their strong coupling to salient sensory stimuli,” Hwaun said. “Because the hippocampus generally receives highly processed information from high-order networks, we did not anticipate that sensory organs could reliably trigger dentate spikes in the hippocampus.”

The team wondered whether these switches between internally and externally focused brain activity were required for proper memory processing.

To find out, they used techniques to block or inhibit dentate spikes in mice and then tested the animals’ memory abilities. Specifically, they attempted to train mice to avoid a chamber where an unpleasantly loud tone would play. Mice normally have no trouble learning this association (this is the same type of classical “conditioning” made famous by Pavlov and his dogs), but when dentate spikes were blocked, the animals struggled to remember to avoid the unpleasantly loud chamber.

This finding suggests that dentate spikes may allow the brain to toggle between internal memory processing and interaction with the external environment, and that this plays a key role in enabling the brain to links new information with existing knowledge of the world.

“There appears to be a rapid switching between remote (represented by sharp wave ripples) and current locations (represented by dentate spikes), which may enable cognitive flexibility that varies with rapid changes in the animal’s internal state or the environment,” Soltesz said.

The researchers are now keen to better understand the role of dentate spikes in memory formation as well as potential contribution to neurological disorders. “Synchronous brain-wide activation during dentate spikes in healthy brains may be exceptionally vulnerable to runaway excitation,” Hwaun said. “Whether dentate spikes develop into pathological activity in epilepsy is an important question that we plan to pursue in the future.”