Why we get dizzy

Welcome back to "From Our Neurons to Yours," a podcast where we criss-cross scientific disciplines to take you to the frontiers of brain science.

This week, we explore the science of dizziness with Stanford Medicine neurologist Kristen Steenerson, MD, who treats patients experiencing vertigo and balance disorders.

In our conversation, we'll see that dizziness is not a singular experience but rather a broad term encompassing a variety of different sensations of disorientation. We learn about the vestibular system, a set of biological "accelerometers" located deep within the inner ear that detect linear and angular acceleration, helping us perceive motion, orientation, and our connection to the world around us.

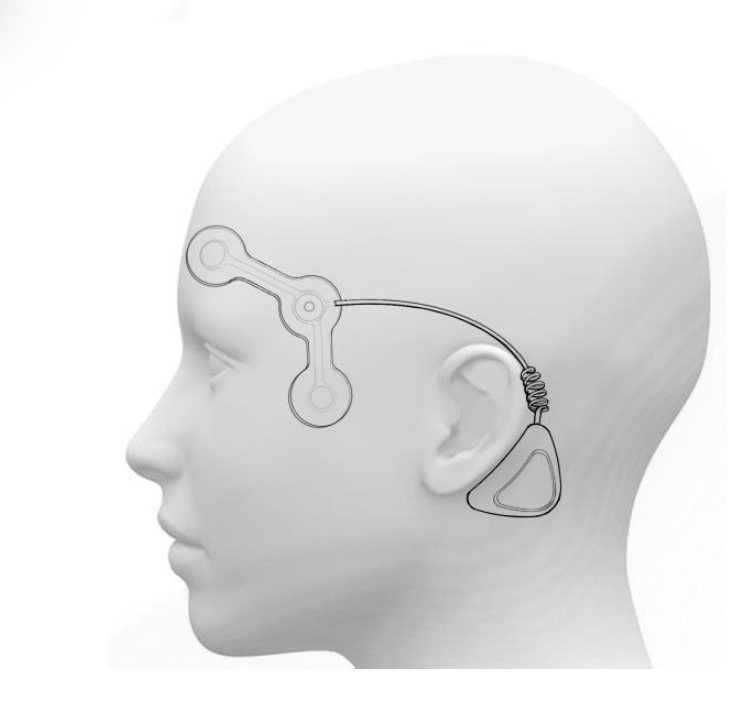

We also discuss a wearable medical device Dr. Steenerson and colleagues at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute are developing a wearable device to measure the activity of the vestibular system by tracking a patient's eye movements. With the ability to study this mysterious system in unprecedented detail, we're on the verge of learning more than ever about this misunderstood "sixth sense."

Listen to the full episode below, or SUBSCRIBE on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music or Stitcher. (More options)

Learn More

Dr. Steenerson's Stanford academic profile

Dr. Steenerson's Stanford Healthcare profile (Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Otolaryngology)

The wearable ENG, a dizzy attack event monitor (DizzyDx)

References

Popkirov, Stoyan, Jeffrey P. Staab, and Jon Stone. "Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness." Practical neurology 18.1 (2018): 5-13.

Harun, Aisha, et al. "Vestibular impairment in dementia." Otology & Neurotology: Official Publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 37.8 (2016): 1137.

Brandt T, Dieterich M. The dizzy patient: don't forget disorders of the central vestibular system. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017 Jun;13(6):352-362. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.58. Epub 2017 Apr 21. PMID: 28429801.

Allison S. Young, Corinna Lechner, Andrew P. Bradshaw, Hamish G. MacDougall, Deborah A. Black, G. Michael Halmagyi, Miriam S. Welgampola Neurology Jun 2019, 92 (24) e2743-e2753; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007644

Episode Credits

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne, with production assistance by Morgan Honaker, and hosted by Nicholas Weiler. Cover art by Aimee Garza.

Episode Transcript

Nicholas Weiler:

This is From Our Neurons to Yours, a podcast from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University. On this show, we crisscross scientific disciplines to bring you to the frontiers of brain science. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler.

We are going to start today's episode deep in the inner ear. Now, we are not in the inner ear to monitor sound but rather to monitor motion. We are surrounded by a series of accelerometers, which help to organize up, down, left, right, top, bottom, and where our bodies are in space. We are in one of the key centers of the vestibular system, our invisible sixth sense that helps our brains and bodies understand orientation and direction. If something gets out of whack here, there's a chance we might experience some form of dizziness. But what exactly is dizziness?

Kristen Steenerson:

So dizziness is an umbrella term to indicate any type of disorientation, sense, or perception that you experience.

Nicholas Weiler:

This is Kristen Steenerson. She's a Stanford physician-scientist who cares for patients experiencing dizziness attacks.

Kristen Steenerson:

That could be a sensation of motion like spinning or tilting or rocking or floating. That could be a sense of depersonalization or dissociation, meaning you don't feel quite connected to your body or the world around you like you're supposed to.

Nicholas Weiler:

So it sounds like there are a lot of different kinds of dizziness, actually. We think of it as one thing, but there are actually a lot of things going on. Can you help us locate that in the brain? What do we know about what causes us to feel these different kinds of dizziness?

Kristen Steenerson:

It's a great question. So our vestibular system is our invisible sixth sense that helps us to understand our sense of motion, our sense of orientation to our own body, our sense of orientation to the world around us, and has direct connections to many different organ systems in our body. So direct connections to our fight or flight system, direct connections to our cardiovascular system, our heart beating, and our blood vessels and our vasculature getting enough oxygen to the brain, and direct connections to our visual system as well as direct connection to our joint position sense. So knowing where your joints are in space.

Nicholas Weiler:

Okay. So it's connected all over the body.

Kristen Steenerson:

All over the body. And the reason is you need all those different components to work perfectly in sync in order for us to feel a normal sense of place and connection to the world around us.

Nicholas Weiler:

And where do those things all come together?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yes. So first of all, you have your inner ear component. So deep within our ears, past your eardrum, past your ear bones, in the inner ear we have our cochlear organ, which is our hearing organ, and right next door, our vestibular organ. So we have five mini-organs that help to detect linear acceleration and angular acceleration or rotation changes.

Nicholas Weiler:

So this is right next to the little sort of snail shell cochlea that lets us here. And above that, there's the vestibular organ. And what does that look like?

Kristen Steenerson:

So the vestibular organ has these three loops that are 90 degrees placed off of each other offset. And then we have two little water donuts, macular organs that are embedded within the vestibule that help to detect those gravity changes or linear acceleration changes in horizontal and vertical planes. From those organs, that information is gathered and then sent through our vestibular cochlear nerve, which is a paired nerve that's helping to bring information from the snail cochlea as well as that three-looped vestibular organ bundle and send that information to our brainstem. From the brainstem, that information is dispersed down our spinal cord, back to our cerebellum coordination center, up to some of the connection points to our eye muscles and our visual targets, and then deep into the brain, out to the outer parts of the brain known as the cortex for some of that more challenging processing and sensory interpretation that helps to give us those more challenging senses of self and feeling connected to the world and oriented, in addition to those individual gravity and acceleration detectors that we're able to do just on the inner ear side.

Nicholas Weiler:

Wow, amazing what our brain is doing without our noticing it just to keep us upright and oriented. I feel like this has been a through line of this show. I feel like almost every episode, our listeners are probably getting tired of me saying, "You don't know it, but your brain is, all the time, doing all of this work that you just take for granted."

So I want to talk just about the experience of dizziness for just a moment. I have kids. They're three and six, and they love spinning around until they can't walk. I remember doing that myself. I don't enjoy it as much now as I did when I was a kid, but why does the brain do this? Why do we get this crazy feeling of the world spinning around?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah, there's a few different reasons. We have two inner ears. So you have two inner ears that are on all the time. It's one of our few senses that never goes to sleep, never takes a break so that we don't have any type of gravity challenge even when we're unconscious. So we have two, meaning that they have to be on perfectly balanced. And if you have an imbalance in one of those, especially if it's suddenly, that creates this really challenging asymmetry for the brain to suddenly have to handle, which it doesn't handle very well, at least in that instantaneous moment.

So a silly, but I think approachable analogy is if you have a motorboat that has two motors and those motors are perfectly linked and powered exactly the same. And then you suddenly cut off one of those motors. You now have this unopposed force coming from one side that's going to shift the balance towards that one direction, and that will create the spinning sensation of the boat. So it's the exact same situation, our motors, our inner ear sense is always on. So if we suddenly cut one off, you have an unopposed force that's going to cause that spending sensation to occur.

Nicholas Weiler:

Is it purely a disorder, or do we think that it has value for us? You said a gravity challenge at some point. What does that mean, and is that one of the reasons why we have this distressing sensation?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah, so we are bipedal, two-legged animals walking around, which doesn't make the most sense when you think of having to battle gravity on a daily basis. So as a result to keep us upright and safe, despite only being on two legs, we have all of these excellent accelerometers or acceleration detectors from the ears linked up to our different back muscles and arm muscles and leg muscles in order to make these micro-adjustments constantly so that we're able to walk around no matter what our gravity changes are, how uneven the surfaces are, how challenging the environment is so that we don't fall. But if that fine-tuned system is even slightly off, that's when we suddenly realize just how many micro-adjustments we're making on a constant basis without having to think about it. And now, when we lose that ability, it can be really devastating.

Nicholas Weiler:

Do we know... As I said, it's very uncomfortable for me to feel dizziness, but my kids really enjoy it. Do we have any idea why that might be?

Kristen Steenerson:

It's a great question people ask me all the time. One idea is that kids are still going through neurodevelopment. So they need a lot more sensory input to start to develop and orient, to understand the limits of the vestibular system, and how to maintain their balance in those more overstimulating circumstances. So kids definitely seem to be more prone towards enjoying the motion, and then as we get older, we're fully neurodevelopmentally matured, that seems to wane.

Nicholas Weiler:

Well, so if this vestibular system is not working properly, people can have quite debilitating dizziness attacks. I know that's what you study in the clinic. And I wanted to ask, is that the same thing as vertigo?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah, so vertigo and dizziness, sometimes, people use interchangeably. If we're being very strict in our definitions, vertigo means a hallucination of movement. So any perception that there's a motion that is there that shouldn't be there. So that could be spinning. It could be a sense of tilting, rocking, floating, any motion at all that you know is not real.

Nicholas Weiler:

And then a dizziness attack could be a broader array of things, like vertigo is one of the things that people might experience in a dizziness attack.

Kristen Steenerson:

Exactly. So sometimes, it's really helpful to clarify with someone, "What do you mean by dizziness? Can you use other words to describe what's going on? Can you give me some examples to try and help understand what their definition of dizziness means? Does it turn out to be actually vertigo or could it be something else like feeling near faintness, feeling anxious, feeling disconnected, or disoriented?" Which is part of the challenge is with understanding what patients mean by dizziness and how to treat them appropriately because there are just so many different interchangeable terms that are used.

Nicholas Weiler:

So this is really hard to diagnose.

Kristen Steenerson:

Terribly difficult to diagnose. But we've talked a lot about how the vestibular system causes dizziness, and that is the vast majority. So at least 50% of dizziness causes are from the vestibular system, but that means 50% are not from the vestibular system, and that's because there can be problems with your cardiovascular system, how much blood flow you're getting to your brain, faintness that may feel like dizziness to some people. You can have medications that can cause side effects. You could have neuropathy that can make it challenging for you to know where your feet are in space. There are lots of different potential other causes, which is why it can be really challenging for a physician trying to evaluate someone's dizziness, sorting out, "Where is this coming from so that I can give you the right treatment?"

Nicholas Weiler:

And so this is one of the things that you're tackling. You've got support from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute to develop a device that people can wear on their faces to diagnose these attacks. Can you give us a sense of what this looks like and how it works?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah. So one of the advantages of the vestibular system having so many connections to other parts of the body is it has direct connections to our eye muscles. And those eye muscles can cause little twitching movements of the eyes so that we can actually get a sense of what the vestibular system function is based on the directions of eye movements, how fast they are when they're occurring, and of course, the direction.

What our device does is it helps to measure those eye movements real time while you're having a dizzy attack so that we can measure when it's happening, how long it's happening for, and the direction, all of those pieces of data to create now a much more discreet picture of what your vestibular system is doing during that attack to understand first, is this vestibular, and then second, what type of vestibular disorder is it. To do that, we have a patch that you wear on your head, and you wear that until you capture a representative event, and then we're able to process that data and give the diagnosis.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's amazing, is it? You can tell from how the eyes are moving what's happening deep in the inner ear, other parts of the brain, that are experiencing vestibular dysfunctions. It goes back to what you were saying earlier about the vestibular system being connected to all different parts of our bodies and our nervous systems to our eyes, our muscles, and our joints and our tendons, our cerebellum, and to our brainstem, and it's really quite remarkable.

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah, we're excited about the potential. It's not available to people very readily and definitely not available in a wearable. But we're even more excited about the future because of just what you said, that this is going to be a window into the vestibular system where, for the first time ever, we should be able to monitor it over long-term and be able to understand those connections to the other organ systems to maybe get so much more understanding of how much the vestibular system is incorporated into our daily lives and other diseases.

Nicholas Weiler:

So this device in particular might both help you get early diagnosis for patients and fundamentally understand the vestibular system better?

Kristen Steenerson:

Exactly. We've never had a monitoring device before.

Nicholas Weiler:

Wow, that's amazing. We talked at the beginning of this conversation about how our vestibular sense is sort of this unappreciated fixed sense that connects us to the world in a way that we maybe don't appreciate all the time. Is that what you're seeing coming out of the literature as your technology and other approaches are allowing us to get a better sense of how this works?

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah. So some really exciting research has come out just in the last few years because we're finally starting to get to a place where we can serially monitor the vestibular system. And one in particular research study has shown that a loss of our inner ear organs, especially the saccule, which is one of those tiny accelerometers for gravity, increases our risk for Alzheimer's disease and particular wandering in Alzheimer's disease. And we think it's because we've underappreciated how much that vestibular orientation system helps us to orient to our own thoughts, to our memory palaces, and has this direct impact on our overall cognition and ability to feel like ourselves and our own body and our own memories.

Nicholas Weiler:

Wow, that's really incredible. It makes me think that we've been talking about balance and the vestibular system and so on in a sort of mechanical way. It's the thing that keeps our body upright. But you mentioned memory palaces, you mentioned connecting with the world around us, and really it does seem... With the experience of dizziness, I think the predominant feeling is a feeling of wrongness. It's as if you're seeing two views of the world at the same time or hearing two different symphonies that are out of tune with each other, but it's your perception of yourself and the world around you. So it feels like you study what happens when people have this feeling of wrongness, but the sense of balance of vestibular system is really important for us feeling right with the world, in a way.

Kristen Steenerson:

Yeah. One of the most common disorders that I'll see in my clinic is something known as persistent postural perceptual dizziness, which is a mouthful, but it's describing people who are having a disconnect exactly that you're referencing where their mechanical receptors work beautifully. We can test them. We have all of our little electrophysiologic studies that show, yep, all of those are working perfectly. But their perception of those mechanical receptors does not align with their actual function. And as a result, they feel these really intrusive, horrible sensations of a persistent, rocking, floating, or dissociative state, despite the fact that those individual mechanical receptors are working appropriately. And that disease process has given us such a beautiful window and understanding how impactful correct perception is and aligned perception is, and understanding the world around you, but also your sense of self.

These people will notice increased anxiety, depression, increased neck pain, and muscle pain because they're walking around with their shoulders tightened and their neck tightened because they're trying to stabilize themselves against a potential vestibular threat with this persistence rocking, floating, swaying sensation, but it's not there. It's really helped us to understand at a more discreet level that perception is a very powerful neuroscience process that is impaired, can completely alter our sense of self, and functionality, which I think is just tip of the iceberg for perception within neuroscience, more globally speaking. That we all have different perceptions, but as long as they resonate with and have a physical checks and balance system to them, we don't even notice that that's a perception process that we're going through. But with this specific vestibular example, we're now understanding, oh, there's a gradation in that perception, and if it's impaired in any way, it can be devastating.

Nicholas Weiler:

Well, I'm so sorry to say it, but I think that that is all the time that we have. Dr. Kristen Steenerson, thank you so much for being on the show.

Kristen Steenerson:

Thank you so much. This is a joy.

Nicholas Weiler:

Thanks again to our guest, Kristen Steenerson. For more on Dr. Steenerson's work, check out the links in the show notes.

We are very excited for season two of From Our Neurons to Yours. If you are too, please take a moment to give us a review on your podcast app of choice and share this episode with your friends. That's how we grow as a show and bring the stories of the frontiers of neuroscience to a wider audience. We'll link to Apple Podcasts reviews in the show notes as well.

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne with assistance from Morgan Honaker. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler.