Your gut - the second brain?

You may have heard the idea that the gut is the second brain, but what does that really mean?

Maybe it has to do with the fact that there are something like 100 to 600 million neurons in your gut. That's a lot of neurons. That's about as many as you'd find in the brain of a fruit bat, an ostrich, or a Yorkshire Terrier.

And it turns out, this network of intestinal neurons, termed by scientists the "enteric nervous system," can actually have a lot of impact on our daily lives – not just in controlling things like our appetite, but may contribute to our mental well-being — and potentially event to disorders ranging from anxiety to Parkinson's disease.

To learn more about this fascinating "second brain", we spoke with Julia Kaltschmidt, a Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute faculty scholar and an associate professor in the Department of Neurosurgery at Stanford Medicine.

Listen to the full episode below, or SUBSCRIBE on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music or Stitcher. (More options)

Links

Regional cytoarchitecture of the adult and developing mouse enteric nervous system.

Hamnett R, Dershowitz LB, Sampathkumar V, Wang Z, De Andrade V, Kasthuri N, Druckmann S, Kaltschmidt JA. Curr Biol. 2022 Aug 31:S0960-9822(22)01307-0. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.08.030. Online ahead of print. PMID: 36070775

Episode Credits

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne, with production assistance by Morgan Honaker and Christian Haigis, and hosted by Nicholas Weiler. Cover art by Aimee Garza.

Episode Transcript

Nicholas Weiler:

This is From our Neurons to Yours, a podcast from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University. On this show, we crisscross scientific disciplines to bring you to the frontiers of brain science. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler. Here's the sound we created to introduce today's topic: your gut, the second brain.

You may have heard the idea that the gut is the second brain, but what does that really mean? Maybe it has to do with the fact that there are something like 100 to 600 million neurons in your gut. That's a lot of neurons. That's about as many as you'd find in the brain of say, a fruit bat, or an ostrich, or a Yorkshire Terrier. To learn more about this fascinating second brain, we spoke with Julia Kaltschmidt, who's a Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute faculty scholar and an associate professor in the Department of Neurosurgery at Stanford.

Julia Kaltschmidt:

Yeah, so the second brain really is a network of nerve cells that line the gut, also called the gastrointestinal tract. And this network is also called the enteric nervous system, and enteric really means "relating or occurring in the gut." And this neural network is so similar to our first brain that it's been coined the second brain. I think the term was coined, I actually looked it up, in 1996 by Mike Gershon. Just to tell you a little bit about Mike Gershon, Mike Gershon is really, I think, one of the fathers of this field of gastroenterology. He actually wrote a book, The Second Brain, and it actually has a subtitle, which is called Your Gut Has a Mind of Its Own. I highly recommend that book. So I believe it's him who coined the term "second brain".

Nicholas Weiler:

So one thing that you said is that this enteric nervous system, the nervous system in the gut, is really similar to our first brain, the brain in our skulls. Can you tell me a little bit about how it is similar and how it is different?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

Sure. So let's talk about similarities first. First of all, it's extensive. It has, as we talked about earlier, more than a hundred million nerve cells. These nerve cells reside within two layers along the entire gastrointestinal tract, so from the esophagus to rectum. In fact, actually, a lot of people, I think about the entire nervous system as being a simpler system, but just for comparison, it has many more neurons than the spinal cord.

Another reason why it's actually similar is that if you think about neural cell types, like a sensor neuron that's senses or a motor neuron that projects muscles, the enteric nervous system also has sensor neurons and motor neurons. The first brain has signal molecules that we call neurotransmitters. Again, the enteric nervous system also has neurotransmitters. In fact, it has over 30 different ones.

And finally, the enteric nervous system or the second brain can operate independently of the first brain. So we can remove the gut from a mouse and can keep it in a medium that allows the cells to survive and the tissue to survive. And we can actually visualize the functioning of the gut, the paracelsus in a dish. So really, the enteric nervous system is what we call a self-sustained or autonomous system.

Nicholas Weiler:

Okay, so it's self-sustained, it's got so many of the same kinds of neurons as in the brain. It's got lots of neurons. It uses neurotransmitters like the brain does. I mean, when I think of the brain... I'm just going to push back on this a little bit and hear how this term is useful or how people should think about this. When I think of a brain, I think of a centralized thing that does computations and is involved maybe in thinking or decision making. So when we talk about the gut as the second brain, is it involved in those kinds of high level things?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

So there's a really interesting question. I think there are some easy answers and some more difficult answers. Can if I may go to the differences first-

Nicholas Weiler:

Sure.

Julia Kaltschmidt:

... and so then I think that gets me then to answering that question. So if you think about the differences, it's clearly location. We have the skull versus the abdominal cavity, and then we get to function. Because we think about the first brain as, for example, controlling voluntary movements or decisions. However, the functions of the second brain are different. When we think of the gut, and this is what the enteric nervous system does, it controls digestion. There are enzymes that are released to digest food, controls the uptake of nutrients, and then muscle contractions and mechanical mixing, but what it really doesn't do is generate a conscious thought process, as we think of it. However, the one thing that it can do is that it can communicate between the gut and the brain, and actually vice versa, also, from the brain to the gut. So there are these nerves that run between the base of the brain and the gut. It's called the vagus nerve and you can think of it as like a street, or maybe more as a highway because the signals are really fast.

Nicholas Weiler:

Why is it useful to think of the enteric nervous system as a second brain?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

So there are a couple of thoughts that come to mind. So when you think about the microbiome that you mentioned before, these are, of course, these trillions of bacteria and microbes that live in our gut, and you have to imagine they reside really closely to the nerve cells that I described that reside within the muscle wall of the gut. Their proximity allows for them to receive signals from the cells or to give signals to the cells. And so I think the research efforts that are currently going on in the field of the microbiome and the gut-brain axis are really important to try to understand how the microbiome or how the bacteria in our gut can influence our mind or our mood. This is an example of how researching or understanding the enteric nervous system and the close associated microbiome are important for our understanding and wellbeing of the mind.

Another point to consider, when thinking about the crosstalk between the gut and the brain, is that gastrointestinal issues such as gastrointestinal dysfunction is very tightly associated with neurological diseases. So for example, Parkinson's disease or autism spectrum disorder, individuals with these diseases oftentimes have colonic dysmotility or constipation. And in fact, when you think about Parkinson's disease, a lot of times constipation precedes the motor symptoms that occur in Parkinson's disease. So there's clearly a very close correlation of gut dysfunction and neurological diseases.

Another example is thinking about generalized anxiety. 60% of individuals with generalized anxiety have irritable bowel syndrome. And again, there, we don't fully understand the link, but there's evidence that an irritated bowel or a dysfunctional bowel might signal to the brain and then that the signals might be responsible in any mood changes that might occur. So when you think about the enteric nervous system, clearly, it's not going to provide conscious thought processes, but it definitely appears to influence our mind.

Nicholas Weiler:

Well, that was something I was going to ask you about. Maybe the second brain in our gut is not thinking, per se. It's not a separate mind. That would be odd. But is it something that we can think about, part of our conscious experience? How do we experience this second gut? Is this nervous system, part of our conscious experience in the way that, say, all of the sensory nerves in our skin and peripheral nervous system that affects us from day to day. People are trying to think more about the mind as a whole body phenomenon, not just a pair of eyes sitting in the skull. So is there an experience that we're getting from this enteric nervous system?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

I would certainly think so, yes. Something that comes to mind, actually, by thinking about an answer for that is, to me... When you think about language, when you're excited, this is saying, "butterflies in my stomach", or you have a "gut reaction" to something, those things. The fact that, actually, the gut became integrated in our language describing decisions, to me, is really telling. It's going to be very interesting to see how the gut influences our decisions.

Nicholas Weiler:

I've seen people write... And I'm curious to know if you buy some of this. I mean, I've seen people write about the enteric nervous system being involved not only in normal GI issues, digestion, and so on, but also influencing emotional affect, motivation, intuition, decision making. Is that going too far? Do we know how much the enteric nervous system is influencing these things? You talked about anxiety, for example.

Julia Kaltschmidt:

I think this is a hard question to answer because I could imagine that it would influence this. And clearly, with the generalized anxiety, there are thoughts that it is actually something that the gut, or the enteric nervous system, or the signals that derive from them affect our mood. So with that example, I'd say yes, the enteric nervous system is able to influence our mind and our decisions.

Nicholas Weiler:

I wonder if you could... I liked your description before. Can you just describe one more time how this nervous system is organized?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

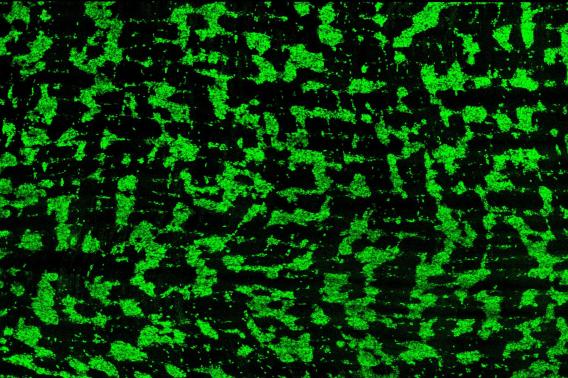

Okay, yes. I'm personally super interested in the organization of the enteric nervous system because until now, there's actually a question of whether the enteric nervous system is organized. So what we do know, clearly, is that it resides within the entire length of the GI tract. It is localized within two sheets, and actually it's these neuronal sheets are intercalated between muscle layers, and we've been very interested to see whether the neurons themselves are organized within these sheets or whether they're different.

For example, when you think about the small intestine versus the colon, because when you think, for example, about different brain regions, there are different neural subtypes in different brain regions, there are differently organized. And so we've been wondering whether there are similarities in associating organization to function. And it turns out that neurons in the gut are organized into rings. So you can imagine that they're these stacks of rings along your GI tract and they're different whether you are looking in the proximal region of the colon or the small intestine. We think that there's a significance to the organization into these rings because that happens shortly before and during birth. It's exciting to think about whether the organization plays a role or influences the establishment of function.

Nicholas Weiler:

I guess I'm still having a little bit of trouble seeing this as a second brain other than the fact that it has a lot of neurons and is in communication with the brain.

Julia Kaltschmidt:

Okay. What are the similarities between the brain and the enteric nervous system? One of them that we talked about is that it's an extensive system. It has a hundred million nerve cells. The brain has clearly a lot more cells, I think it's in the 90 billion nerve cells, but it has a lot. A lot more than the spinal cord. The neurons are forming a network, so they are signaling to each other. The same happens in the brain.

If you think about the different neural subtypes that you can find in the brain that can be defined, for example, by their interconnectivity, their function, their expression of different neurotransmitters, the same happens in the enteric nervous system. So we have different cell types and they're classified to be sensory neurons, border neurons, interneurons, and they have been shown to produce different neurotransmitters. There is not exactly the same co-expression, potentially, of neurotransmitters, but we have 30 different neurotransmitters in the enteric nervous system. So the building blocks that make up the brain also make up the enteric nervous system. And again, the fact, I think, personally, the fact that it's a system that can function by its own, it can create paracelcus on its own without the brain, I think is significant.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's great, thank you. I have one more question. Can you tell me... I mean, to you, what are some of the most exciting open questions in this field that we don't know yet and that you're excited to find out more about?

Julia Kaltschmidt:

I think... I mean, to me, what we'd love to do is to understand how the enteric nervous system is organized and how this organization contributes to function. I think it'll be extremely interesting for the field to understand how, for example, the microbiome influences potentially the enteric nervous system, and hence, also then via that, the signaling to the brain. I think this huge possibility and opportunity for neurological diseases, which are currently treated in the brain to potentially be having a different access via the gut, via the enteric nervous system. I also think that we don't know very much about understanding the early onset of the functioning of the gut at all. So I think, personally, I think this is a super exciting question.

Nicholas Weiler:

That sounds like a really exciting place to be working right now. Thanks so much for taking the time and speaking with us.

Julia Kaltschmidt:

Thank you, Nick, for having me. I enjoyed speaking with you.

Nicholas Weiler:

Thanks so much again to our guest, Julia Kaltschmidt. To learn more, check out the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at neuroscience.stanford.edu. For more info about Julia's work, check out the links in the show notes. This episode was produced by Michael Osborne with production assistance by Morgan Honaker and Christian Higas. I'm your host, Nicholas Weiler.