I'm a neuroscientist. I'm not worried about how screens will affect kids' brains — here's why.

David Eagleman

Given that the brain becomes wired from experience, what are the neural consequences of growing up on screens? Are the brains of digital natives different from the brains of the generations before them?

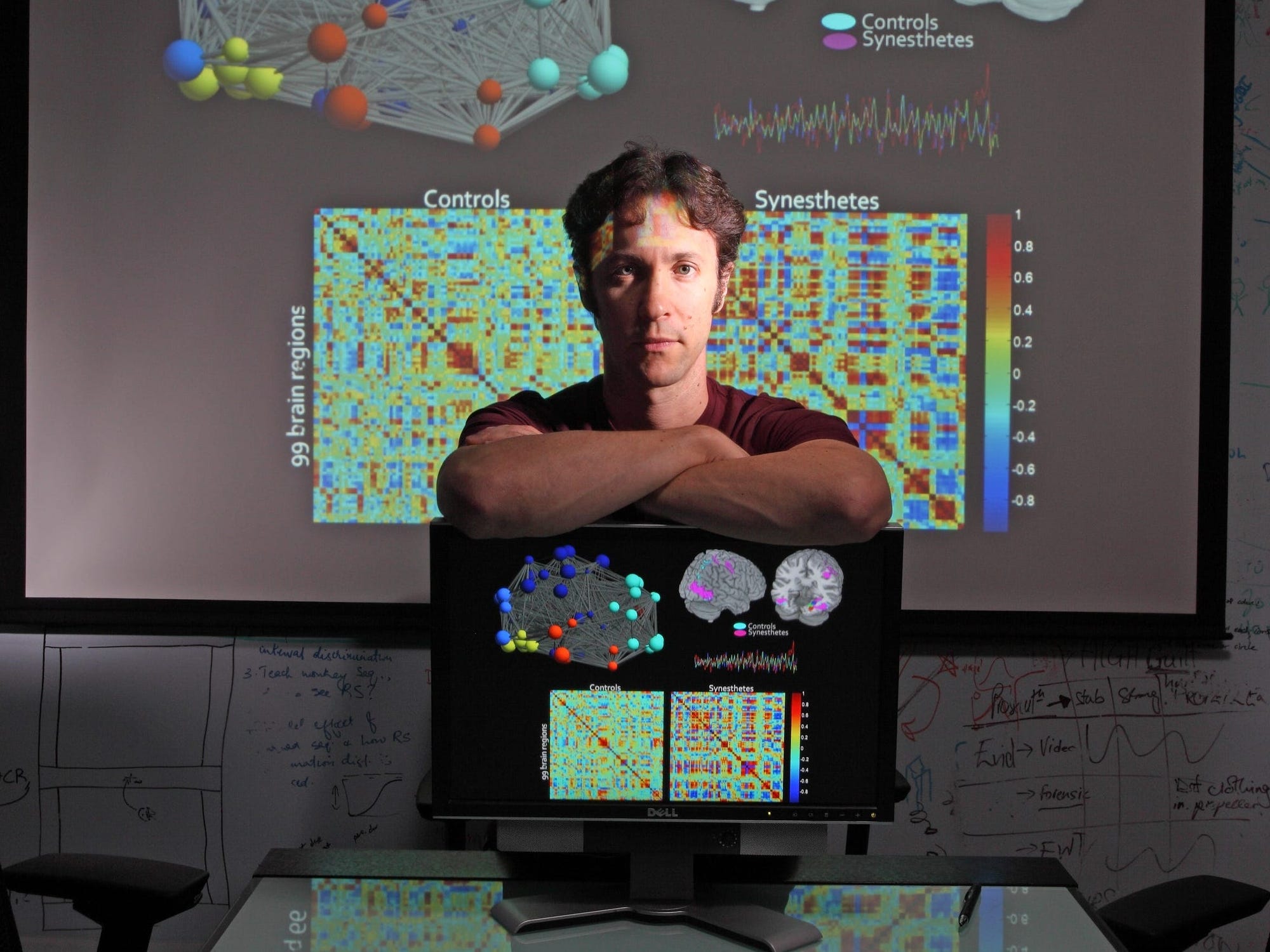

David Eagleman

Photo: Toby Trackman

It comes as a surprise to many people that there aren't more studies on this in neuroscience. Wouldn't our society want to understand the differences between the digital- and analog-raised brain?

Indeed we would, but the reason there are few studies is that it is inordinately difficult to perform meaningful science on this. Why? Because there's no good control group against which to compare a digital native's brain.

You can't easily find another group of 18-year-olds who haven't grown up with the net. You might try to find some Amish teens in Pennsylvania, but there are dozens of other differences with that group, such as religious and cultural and educational beliefs.

Where else can you find young people of the same age who don't have access to the internet? You might be able to turn up some impoverished children in rural China, or in a village in Central America, or in the deserts of Africa. But there are going to be other major differences between those children and the digital natives whom you intended to understand, including wealth, education, and diet.

Perhaps you could compare millennials against the generation that came before them, such as their parents who did not grow up online — but who instead played street stickball and stuffed Twinkies in their mouths as they watched The Brady Bunch. But this is also problematic: between two generations there are innumerable differences of politics, nutrition, pollution, and cultural innovation, such that one could never be sure what brain differences should be attributed to.

So it is an intractable problem to pull off a well-controlled experiment about the effect of growing up with the internet.

Nonetheless, I can tell you the root of my optimism.

Never before have we had the entirety of humankind's knowledge in a rectangle in our pockets, with constant and immediate access. Some readers will remember trips to the library: We would pull out a volume of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (say, for the letter H) and we would flip through to the detail we wanted. The article had been written sometime in the previous decade or two. We'd hope it was sufficient, because otherwise we'd have to thumb through the card catalog and pray there was other material to be found at that library. And then our parents would take us back home because it was dinnertime.

In a surprisingly brief period, this has all changed. As a result, we've all seen the transition of dinnertime debates: The winner has transitioned from being the most vociferous or persuasive to the person who can whip out the phone the fastest and google the fact in question. Discussions move rapidly now, leaping from one solved question to the next.

And even when we're by ourselves, there is no end to the learning that goes on when we look up a Wikipedia page, which cascades us down the next link and then the next, such that six jumps later we are learning facts we didn't even know we didn't know.

The great advantage of this comes from a simple fact: All new ideas in your brain come from a mash-up of previously learned inputs, and today we get more new inputs than ever before.

Children now live in a time unparalleled in richness: Our knowledge sphere has exploded in diameter, and as it grows it offers more doors for entry. Young minds have the opportunity to cross-link facts from completely different domains to generate ideas that previous eras couldn't have imagined.

And this partially explains the exponential increase in human scholarship: we have faster communication and more mash-ups than ever before.

It's not clear what all the social and political consequences of the internet will be, but from a neuroscience perspective it is poised to unlock a much richer level of education.

Excerpted with permission from "LIVEWIRED: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain" by David Eagleman.

David Eagleman is a neuroscientist at Stanford University, an internationally bestselling author, and a Guggenheim Fellow. He is the writer and presenter of The Brain, an Emmy-nominated television series on PBS and BBC. Dr. Eagleman's areas of research include sensory substitution, time perception, vision, and synesthesia.