Microscopy technique helps reveal how oligodendrocytes wrap around neurons

Cells pull themselves through the world with the help a complex internal protein scaffold called the cytoskeleton. Given the ubiquitous role of that structure in cell movement – particularly a protein called actin – it seemed likely those same proteins would be involved in helping a group of cells called oligodendrocytes wrap themselves around and insulate neurons.

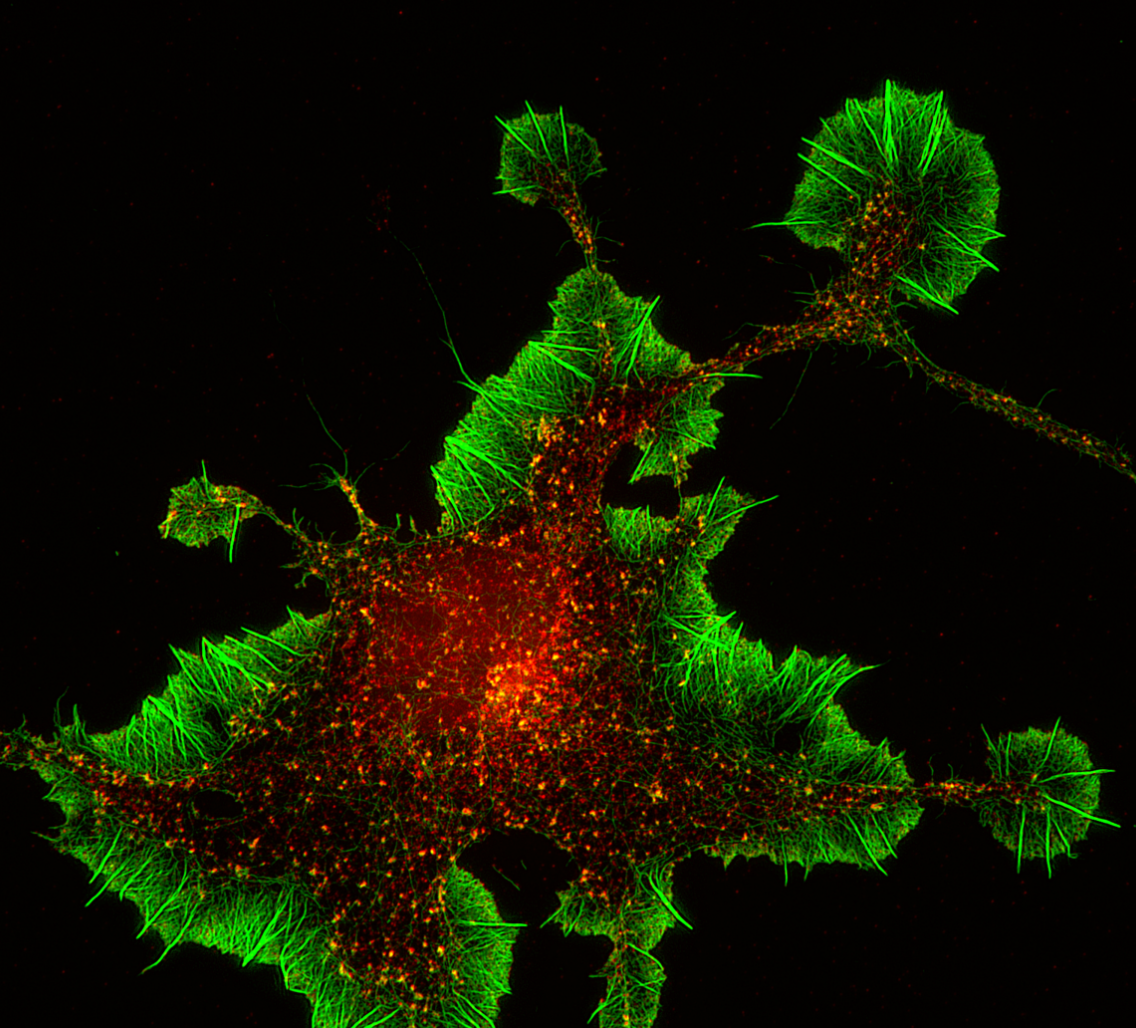

That, at least, was the idea Brad Zuchero started with when he joined the lab of Ben Barres, professor of neurobiology, as a postdoctoral fellow. However, his paper in Developmental Cell, published July 9, shows a slightly different story. What Zuchero found is that although the actin lattice fans out at the edges of oligodendrocytes as they move, the actin network essentially melts before the wrapping begins.

“What was crazy is that the opposite thing happened than what we’d expected,” Zuchero said.

While Zuchero was working on this project he got a request from Andrew Olson, who runs the Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service. Olson needed samples to use in testing new microscopes for the facility. Zuchero gave Olson one of his oligodendrocytes and not long after Olson sent Zuchero an image showing the intricate actin network at the edges of oligodendrocyte, taken on one the microscopes he tested.

“I thought, wow you can actually see the structures within the oligodendrocyte,” Zuchero said. “It completely ruined me for other microscopy.”

That fine resolution was thanks to a relatively new form of microscopy called structured illumination microscopy. Most microscopes can only image structures that are larger than about 200 nanometers. Anything smaller than that gets dwarfed by the larger wavelength of visible light. The microscopes Olson was testing and that he eventually purchased for the facility can reveal structures as small as about 120 nanometers – or smaller under some conditions.

“I found that there’s a striking transition where there is a cytoskeleton – and that’s what you see in the super-resolution images – but then right at the time when oligodendrocytes begin wrapping this scaffold melts away,” Zuchero said.

Olson continued working with Zuchero after he purchased the new microscope for his facility. At that time, Zuchero had been trying to understand what triggered actin to disassemble. It seemed that a protein called myelin basic protein (MBP) was involved, and some other studies had suggested that MBP interacts with actin to promote its disassembly. But Zuchero’s work in the lab suggested that actin and MBP weren’t interacting.

Then one day, Olson sent Zuchero an image showing an intricate lattice composed of MBP surrounded by – but not touching – actin. “It perfectly confirmed everything we thought was going on,” Zuchero said. “That was the nail in the coffin.”

Now Zuchero hopes to understand how this novel mechanism for cell movement occurs. He said in the course of reviewing the literature he discovered that a number of human diseases that result from improper wrapping of oligodendrocytes around neurons have genetic links to the cytoskeleton, making the work of possible relevance to those diseases.

He plans to continue using super-resolution microscopy to understand myelination and neuron-glial interactions here at Stanford, and in the future in his own lab.

The Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service, which is supported by the Stanford Neurosciences Institute, is a service center available for use by anyone in the Stanford research community. Contact Andrew Olson at aolson6@stanford.edu for information.