By Dana G Smith

A mouse hangs out in a cage, oblivious to the wire sticking out of its head and recording its brain activity. The mouse strolls around before making its way to the corner where a food pellet — full of fat and extra delicious — lies. The mouse takes a bite and then keeps eating and eating and eating. A graph measuring the mouse’s brain activity goes crazy, spiking upward again and again and again.

Another mouse with an identical wire is in an identical cage with an identical food pellet. When it walks over to the pellet, there is a similar jump in its brain activity. But before the mouse can tuck into the food, a tiny electric shock passes through the wire into the mouse’s brain. The mouse turns around and walks away. Every time the mouse moves toward the pellet, its brain activity peaks, the electrical stimulation starts, and the mouse changes its mind and reverses course.

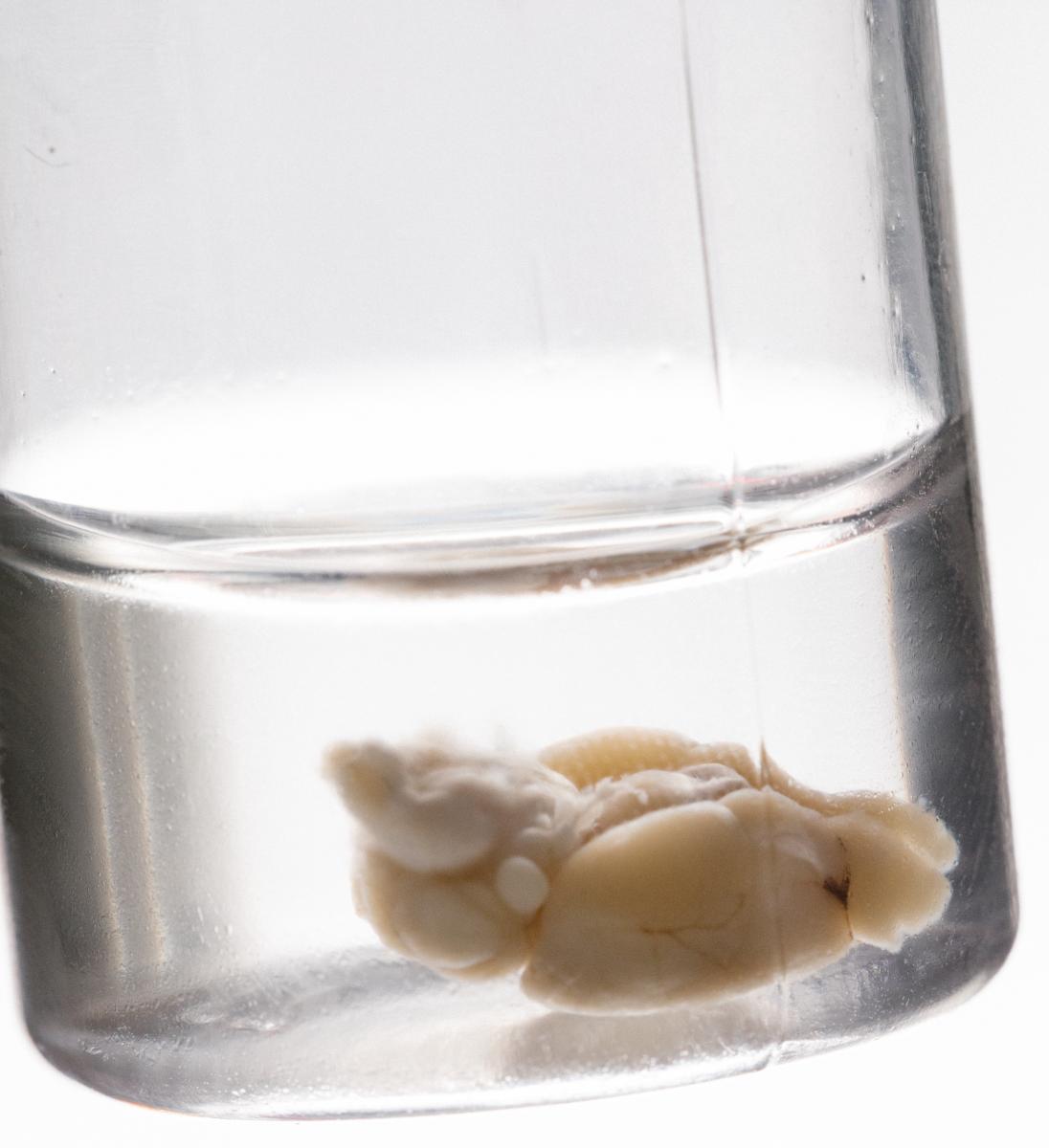

A mouse brain in a vial in the lab of Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University.

A mouse brain in a vial in the lab of Casey Halpern, MD, at Stanford University.

These mice are trained to binge eat by scientists who expose them to high-fat food and then take it away. Eventually, the mice learn that the tastier chow is available only in a narrow time frame, so they load up on it while they can, consuming as much as 100% of their daily calories in just one hour. In 2017, researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine decoded the unique pattern of brain activity that predicts when the mice are about to gorge themselves. They also showed that delivering a minor electric jolt in response to that neural activity snaps the mice out of it, stopping the binge before it starts.

“When we stimulate this area in the mouse, we block binge-like behavior by at least 75%, ” says Casey Halpern, MD, an assistant professor of neurosurgery and director of epilepsy surgery at Stanford, who led the research.

Halpern is now launching a clinical trial to test this same procedure in people who are obese and experience what’s called “loss-of-control eating,” which he defines as regularly eating in the context of craving, eating more than you plan, or not being able to stop yourself from eating once you start. Most people have likely experienced these types of feelings on occasion, but Halpern makes it clear that the procedure is not intended for people who are trying to lose a little bit of weight. To be eligible for the study, people must also have a body mass index (BMI) of over 45 and not have lost weight from previous treatments for obesity, including gastric bypass surgery and cognitive behavioral therapy.

“These are patients who are essentially dying of their obesity,” he says.

The technology Halpern is using to record and stimulate brain activity — called a responsive neurostimulation system (RNS) — was originally developed by the biotech company NeuroPace to treat severe epilepsy. Electrodes are inserted into two specific areas of the brain, and a tiny computer and battery pack are implanted into the skull. The entire system is neatly packaged and invisible from the outside (unlike the system in mice). Inside the brain, the electrodes record continuously, and when they detect a specific pattern of activity that signals the onset of a seizure, they automatically deliver a mild electric shock to stop the seizure short.

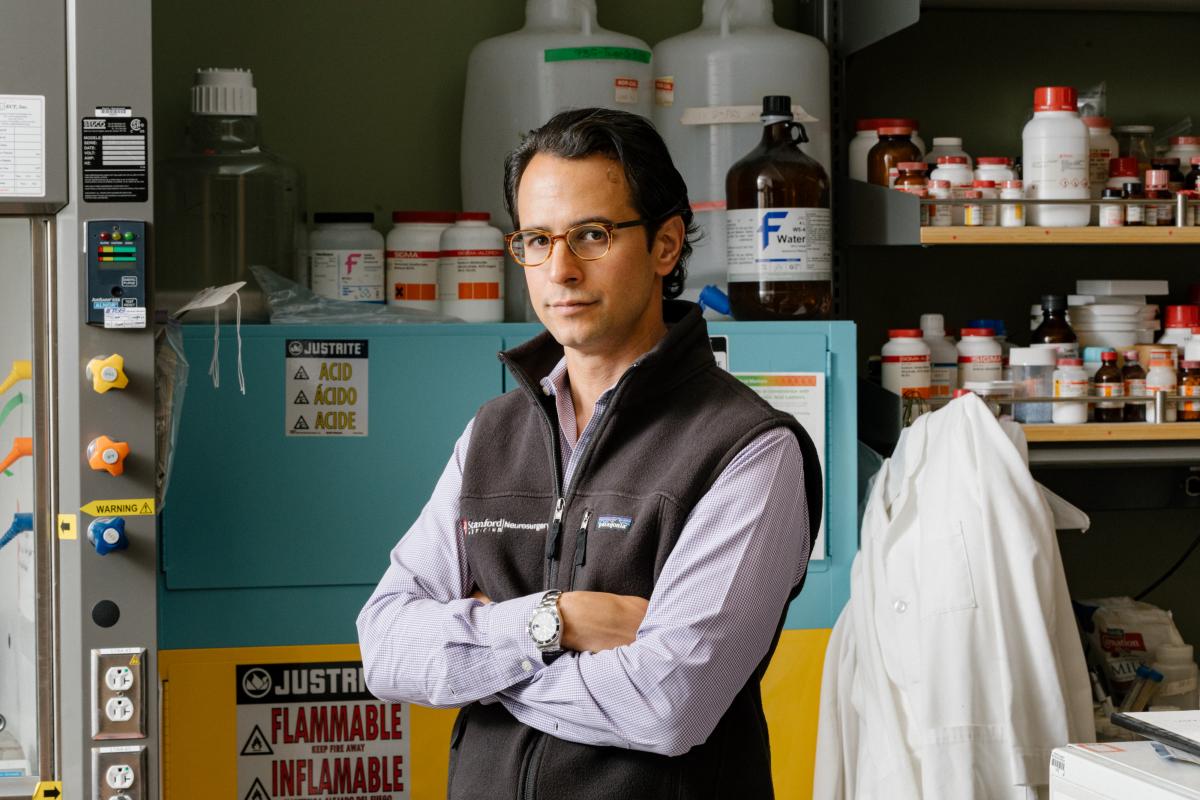

Casey Halpern, MD, in his lab at Stanford University.

Casey Halpern, MD, in his lab at Stanford University.

“What our device can do… is define normal patterns and then define deviation from normal,” says Martha Morrell, MD, PhD, and chief medical officer at NeuroPace. “It’s not like you’re chasing the symptoms, it is that you are preventing the symptoms. And that is a very attractive approach to not only impulse control disorders, but also to any episodic neurological condition.”

In the new study, Halpern, along with colleagues at Stanford and NeuroPace, are testing whether the device can detect and stop other harmful patterns of brain activity, like the start of a food binge. Over the course of five years, the trial will enroll six people and follow each of them for at least 18 months. The goal is first to determine if the procedure is feasible and safe, and then, hopefully, effective.

While the procedure is extreme, so is the condition it’s addressing. Morbid obesity, defined as having a BMI of 40 or higher, is associated with medical problems that can include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, and even dementia. There are few effective, sustainable treatments besides gastric bypass surgery, and that procedure is permanent and comes with the risk of severe side effects.

“Knowing what we know about obesity and dementia and metabolic dysfunction and health in general, I would go for extreme measures,” says Dana Small, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and psychology at Yale University and director of the Modern Diet and Physiology Research Center, who is not involved in the study. “I mean, we already take out the gut — that’s already pretty extreme.”

Other clinical trials have used a similar approach called deep brain stimulation (DBS) to try to treat obesity, with limited success. DBS, which is most commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease, delivers a continuous electrical current whereas RNS emits a shock only when it detects the target pattern of activity.

The earlier DBS trials to treat obesity also focused on an area of the brain called the hypothalamus, which controls hormone levels involved in feelings of hunger and satiety, as well as the body’s metabolism. In theory,

stimulating the hypothalamus will increase metabolism, helping someone burn more energy and lose weight. In practice, the results were inconsistent.

The NeuroPace device.

In one trial, conducted in Brazil, one person out of the six test subjects successfully lost more than 100 pounds. Three of the others lost some weight but not a substantial amount, and the remaining two did not lose any weight. In another study at the Allegheny Singer Research Institute in Pennsylvania, only one person out of three lost weight and kept it off.

Antonio De Salles, MD, chief of neuroscience at Hospital do Coração in São Paulo, who led the Brazilian research, speculates that the reason for the lackluster results is that people in the study increased their food consumption to compensate for their higher metabolisms. While they were burning more calories, they were also eating more calories. He thinks these people might fit Halpern’s criteria for loss-of-control eating and would benefit from having a different part of their brain stimulated.

Instead of targeting the hypothalamus, Halpern is focusing on an area called the nucleus accumbens — the brain’s pleasure center, which is integrally involved in feelings of reward and addiction. Whenever you experience something pleasurable, whether it’s spending time with friends, listening to music, or having an orgasm, the nucleus accumbens lights up. It’s also particularly reactive to foods high in fat and sugar, the ones people are most likely to crave.

Research has shown that people who are obese have more activity in the nucleus accumbens in response to images of high-calorie foods. Another study revealed that the greater the nucleus accumbens response is to food, the more likely someone is to gain weight.

“There is a lot of evidence to suggest the nucleus accumbens is an important target,” says Small. “There are many studies looking at brain response to food cues, and the nucleus accumbens is very frequently activated and associated with all kinds of factors that are associated with risk for overeating or developing obesity.”

After implanting the device, the researchers will record activity from the nucleus accumbens for six months before turning on the stimulation. They will monitor the people’s brain activity both when they’re at home and in the lab performing experiments that tempt them to binge, like having free access to pizza and ice cream. When they’re on their own, the people in the study will note every time they have a binge episodes so the scientists will know to analyze their brain activity at those specific times.

“In mice, we’ve been able to define brain activity that predicts a binge fairly reliably, and it’s a very reproducible, robust signal that guides stimulation,” Halpern says. “We don’t know what a binge looks like or what food craving looks like in a human, so we need to define that first.”

Casey Halpern, MD, talking with students in his lab at Stanford University.

This step is crucial because the researchers don’t want the stimulator to turn on when people are eating a healthy meal or when they feel pleasure from another activity. In the mice, the researchers didn’t impact normal eating or social behavior. However, in an initial pilot study in one person with the implant, the opportunity to win large sums of money caused a pattern of activity similar to the one the mice had just before a binge. On the one hand, this confirms that the pattern of brain activity is likely the same, making the researchers’ job easier. On the other, it suggests the activity is not specific to food cravings and can be generalized to other highly enticing rewards.

Along these lines, a major concern for the study is that the stimulation could cause feelings of depression or anhedonia — a loss of interest in things and a general inability to experience pleasure. However, Halpern thinks that when the stimulation is turned on, it is more likely to affect people’s mood in a positive way. Supporting this theory, people with obsessive compulsive disorder who have undergone DBS in a neighboring area of the brain report that the treatment improves their feelings of anhedonia and depression.

The treatment — not surprisingly — is controversial. Kathryn Ross, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Florida, says that people’s eating behavior is more complex than one brain region or behavior.

“There’ve been a couple times where we think there’s this wonder drug on the market that can help curb appetite or help people not eat impulsively. And time and time again, those drugs have been found to be effective only short-term or for certain populations of people,” she says. In other words, the drug might work for some people with very specific impulses and symptoms, but not for others whose weight gain is not related to bingeing.

Instead, Ross says that behavioral change is the sole method consistently proven to help with permanent weight loss. Even extreme interventions like gastric bypass surgery are effective long-term only when paired with behavioral changes. Otherwise, people can override the benefits of the therapy by going back to their old behaviors.

“As much as folks are always looking for the new greatest thing, the basic truth of managing weight really hasn’t changed for a long time: it’s eating less and moving more,” Ross says. “I don’t think there’s a quick fix without helping people change their behavior more broadly.”

Halpern admits that the surgery “is undoubtedly more invasive than taking a medicine or cognitive behavioral therapy.” But, he says, “as a neurosurgeon, it’s the least invasive surgery that I can offer a patient.”

What’s more, the procedure is less risky than gastric bypass surgery, which involves removing, rerouting, or restricting part of the stomach and can cause severe and permanent side effects, such as bowel obstruction, dumping syndrome, and stomach perforation. In comparison, a major benefit of neurostimulation is that it can easily be switched off if people don’t like it or experience side effects.

“The surgeries that exist for obesity today are extremely aggressive,” says De Salles, the Brazilian neurosurgeon. “Bariatric surgery is very effective. It works, people lose weight rapidly. But there are consequences and side effects that we need to try to avoid.”

There is also the question of whether people would be willing to undergo brain surgery to lose weight, as well as if they should.

Virginia Sole-Smith, author of The Eating Instinct: Food Culture, Body Image, and Guilt in America, says that the problem with any kind of weight-loss surgery is the “foregone conclusion that this is a problem we need to solve by any means necessary.”

Instead, she says, changes to the environment to better accommodate larger bodies and reducing stigma around weight would be more beneficial to people by helping to alleviate their daily stress and discomfort.

“Is it phenomenal what we can do in the brain? Sure,” she says. “What depresses me about this study is it’s saying we can solve the problem by making these people smaller instead of looking at the systemic problem in our health care system about how we treat people in higher-weight bodies.”

Most important is what the people signing up for the study say. According to Tricia Cunningham, a clinical research coordinator at Stanford who is leading the recruitment and day-to-day running of the trial, one candidate she spoke with felt all along that “they should have had brain surgery instead of their gastric bypass to address their issues.”

Now they’ll have the chance. And hopefully, changes to the environment won’t be far behind.