Brain-Computer Interfaces

Imagine being trapped in your own body, unable to move or communicate effectively.

This may seem like a nightmare, but it is a reality for many people living with brain or spinal cord injuries.

Join us as we talk with Jaimie Henderson, a Stanford neurosurgeon leading groundbreaking research in brain-machine interfaces. Henderson shares how multiple types of brain implants are currently being developed to treat neurological disorders and restore communication for those who have lost the ability to speak.

We also discuss the legacy of the late Krishna Shenoy and his transformative work in this field.

SUBSCRIBE on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music and more.

Learn more

Henderson's Neural Prosthetics Translational Lab

BrainGate Consortium – "Turning thought into action"

Commentary on Neuralink's brain-interfacing technology by Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Faculty Scholar Paul Nuyujukian (WIRED, 2023; NBC Bay Area, 2024)

Brain Implants Helped 5 People Recover From Traumatic Injuries (New York Times, 2023)

- Related publication: Nature Medicine, 2023

Brain to text technology is about more than Musk (Washington Post, 2023)

- Related publication: Nature, 2023

The man who controls computers with his mind (New York Times Magazine, 2022)

Software turns ‘mental handwriting’ into on-screen words, sentences (Stanford Medicine, 2021)

- Related video: Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, 2021

- Related publication: Nature, 2021

Learn about the work of the late Krishna Shenoy

Krishna V. Shenoy (1968–2023) (Nature Neuroscience, 2023)

Krishna Shenoy, engineer who reimagined how the brain makes the body move, dies at 54 (Stanford Engineering, 2023)

Using software engineering to bring back speech in ALS (Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, 2023)

Episode Credits

This episode was produced by Michael Osborne, with production assistance by Morgan Honaker, and hosted by Nicholas Weiler. Cover art by Aimee Garza.

If you're enjoying our show, please take a moment to give us a review on your podcast app of choice and share this episode with your friends. That's how we grow as a show and bring the stories of the frontiers of neuroscience to a wider audience.

Episode Transcript

Nicholas Weiler:

This is From Our Neurons to Yours from the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University. Each week we bring you to the frontiers of brain science to meet the scientists unlocking the mysteries of the mind and building the tools that will let us communicate better with our brains. Today, brain-machine interfaces.

Imagine being trapped in your own body. You can think, you can feel, but you can barely move. You have things you want to say to the people around you, but your mouth won't form the words. Or imagine that you still can move, but your mind no longer works the way it used to. Everyday thinking is slow and exhausting. Familiar memories are locked behind closed doors. These scenarios may sound like nightmares, but they're common experiences for the many people living with brain or spinal cord injuries. The numbers may surprise you. The CDC estimates roughly 1 in 50 Americans, in other words 2% of the population is living with a disability as a result of traumatic brain injury.

As we've seen again and again on this show, there's a huge amount of work the brain is doing for us without our awareness, so even partial losses of function can be devastating. And historically, our ability to help people with brain injuries has been extremely limited, but this is finally beginning to change. There are two main reasons that we may be at a turning point in neurology.

First, we simply know more about the brain than ever before. While my mysteries still abound, we are making ever more progress in pinpointing the functions and interactions of key brain regions and circuits. Second, advances in machine learning like those that are driving revolutions in AI, are allowing scientists to find patterns in complex neural data and begin to decode the inner language of the brain. The combination of these factors is opening new doors to developing effective brain implants to directly treat neurological disorders.

This week's guest is at the forefront of this field. Jaimie Henderson is a neurosurgeon whose lab is developing some of the most advanced brain machine interfaces in the world and leading exciting clinical trials to bring these advances to patients.

Jaimie, thank you so much for coming on the show.

Jaimie Henderson:

My pleasure. Thanks for having me, Nick.

Nicholas Weiler:

And I'd love to start by talking about a study that's been in the news recently. So traumatic brain injury is one of those things that for many years it's been sort of received wisdom that once the brain's damaged, there's very little we can do directly to repair it. People can work through physical therapy to bring back some function, but the actual damage to the brain was thought to be too complicated to directly repair. But in this new study with your collaborator, Nicholas Schiff, you showed that this may not always be the case.

Before we talk about what you did, can you help us understand a little bit about how severe the long-lasting symptoms of brain injury can be? What are these patients experience as a consequence of their injuries?

Jaimie Henderson:

Yeah. Brain injury is very under-recognized, in my opinion. The suffering that some people go through even after having recovered to a stage where they're able to go back to work or back to school, interact normally with friends and colleagues to some extent, they still know that they're not the same person that they were before the injury. And interestingly, since this study was published, we've gotten lots and lots of emails, as you might imagine, from people who are in the same boat, who people look at them and say, "Hey, you've recovered great. You should be very happy." But they know that there are still significant deficits in the way that they interact with the world.

As an example, someone who might've been going to graduate school prior to their injury may now no longer be able to read more than a few sentences before having to give up, without being able to put those thoughts together into a coherent whole. One of the examples from this study was a young woman who had had a brain injury 18 years earlier. She hadn't read a novel since that time. After the deep brain stimulator was placed and activated, she read three and was able to retain them, follow the plot, and it was a complete change in her ability to process information.

It really is something that we haven't been able to treat very well. There are really no good treatments for brain injury. And so this is really one of the first interventions to show some promise and some hope for these patients.

Nicholas Weiler:

Well, that's really remarkable, the level of improvement that these patients see. And as you say, there's just nothing else. So let's get into it. Could you describe the device you implanted? What does it look like and what is it doing? How is it controlled?

Jaimie Henderson:

Yeah, so we're using a standard deep brain stimulation device. It consists of a pacemaker like device that's implanted in the chest. And then two electrodes, one placed on each side of the brain. These are 1.2 millimeters in diameter, so about the size of a large pencil lead. And they go to a target pretty much right in the center of the brain in an area called the thalamus, which is about the size and shape of a walnut. And the target that we're aiming for is about like an almond shell. So it's a very small target deep in the brain.

We then anchor those electrodes, those wires, to the skull, and then they're tunneled via an extension from the scalp down to the chest and connected. And the stimulator runs all the time, it's continuous stimulation. But for these patients, because the point of the stimulator is to increase their level of attention and arousal, we want to turn it off at night because we don't want to keep them up and keep them sleepless. So you have to have a little bit of break from the stimulation. And so we turn it into a cycling mode where it's on during the day and then off at night.

Nicholas Weiler:

Wow. So you say this is a standard deep brain stimulation device, and so you and others use a similar device for patients with Parkinson's, right, to sort of reactivate parts of the brain that become inactive because of that neurodegenerative condition. But in this case, you're activating a different part of the brain that you think is impaired or suppressed after people experience traumatic brain injury.

So why do we think this is improving the patient's symptoms? You're not just overdrive the brain, right? You think this is something that is involved and is impaired after brain injury?

Jaimie Henderson:

That's right. Yeah. And this is one of Dr. Schiff's real contributions to our understanding of brain injury. He's dubbed this the Mesocircuit Theory, and the idea is that in a brain injury, there's been disruption to some of the normal connections, and oftentimes that's rather a diffuse disruption. But those connections aren't completely severed, they're just down-regulated. So there's a feedback loop between the outer part of the brain, the cortex, and the thalamus, this deep structure that we're targeting. And this circuit is self-reinforcing. And so with reduction in the input to the cortex from the brain injury, the cortex then in turn gives less input to the thalamus, which in turn gives less input to the cortex. So the entire circuit just sort of winds down. It's like turning down the dimmer switch on a light.

And so what theory is, well, by stimulating this particular target in this particular pathway we can maybe turn that dimmer switch back up again and allow people to engage those circuits in ways that they hadn't been able to do before.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's really amazing that you can now target this brain wide networking defect with an implant and have it sort of ongoing and see these huge improvements. I mean, some of the quotes, we'll include links in the show notes, I mean, some of the things that you heard from these patients was really remarkable. It's restoring their ability to live and work. And I do want to manage expectations here for listeners a little bit. This study was a proof of concept with five patients, but now you're planning a larger clinical trial. Is your hope that this could work for a wide range of people with brain injuries?

Jaimie Henderson:

That's the hope. Obviously, as you mentioned, this is proof of concept. It's a small study. It was open label, meaning it wasn't really blinded. We tried to do a blinded portion to try to see if there was any placebo effect. But interestingly enough, a couple of the patients refused to participate in that blinded portion of the trial because they had either, one, had their stimulator accidentally deactivated or two purposely deactivated the stimulator. And in both cases, they were unhappy with the results of that. And so they said they didn't want to have it turned off again. So they were clearly getting benefit from it. But again, as you said, manage expectations. This is a small study, and so that remains to be seen.

Nicholas Weiler:

It is just remarkable, even with a proof of concept study that we now have the ability to diagnose that a brain circuit's not performing in the way that it ought to and tweak it and really see benefits for patients. And I have to say, Jaimie, this was all the more impressive to learn about because it exposed me to a whole other area of your work that I hadn't been as familiar with. Because I mostly know about your other transformative work for patients with neurological disorders. I'm talking about the work that you've been doing for more than a decade with Krishna Shenoy developing a completely different type of brain implant to help restore language to people who can't speak due to paralysis.

And for listeners, tragically, Dr. Shenoy passed away last year after a long battle with cancer. We can never do justice to everything that Krishna meant to this field. But I want to do our best in the short time we have on this episode to talk about the impact of this work and what it means for people who have lost the ability to speak due to various forms of paralysis.

Let's start by stepping back a little bit. When people envision a speech prosthesis for someone with paralysis, most people probably still think about the physicist Stephen Hawking and his computerized voice. I wonder if you could tell us sort of where the clinical state-of-the-art art has been, what's available to most people right now, and how the approaches you and Krishna and your collaborators have developed are different from that?

Jaimie Henderson:

Yeah. So you mentioned Stephen Hawking and his interface, that's a very old device. And Professor Hawking had many offers to upgrade that system and to make it better. But this is really illustrative of assistive technologies in that he said he was used to it, he knew how it worked, he didn't want to try something new because he already was comfortable, even though the system itself was quite limited. And this is what happens oftentimes is various assistive technologies are developed, they're deployed to people with particular conditions, and then they go in the closet because they really can't use them, they're inconvenient or bulky or have some other problems or issues. And that's true of many of the assistive technologies today for people with communication disorders.

They range from things like eye trackers, which allow people to either spell words out by looking at a particular part of the screen and then blinking or moving a muscle if they're able to. There's the very old-fashioned way of having an assistant scan a finger across a letter board and then blinking when that person reaches the letter that you want to spell. I'm sure many listeners are familiar with the book, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, which is the story of the former editor of Elle Magazine who had a brainstem stroke and was left unable to move anything except one eye. And he wrote the entire book using that method.

So there really are limited options for people with communication disorders. Some of them are actually pretty clever and quite good, but we need more. We need to be able to hopefully one day allow people to communicate at speeds and accuracies approaching that of what we're doing right now.

Nicholas Weiler:

Yeah, I mean, we had a previous episode with new faculty member Laura Williams, where we talked just about how effortless and natural speech is for us usually. And so imagining the effort that would have to go into operating one of these systems, it's hard to imagine if you haven't had to do it or see it.

Jaimie Henderson:

Absolutely.

Nicholas Weiler:

So could you talk a little bit about the brain implants you have been using in these studies for developing a better way of allowing people to communicate directly using their brain activity? What are those implants and what kind of activity are you reading out?

Jaimie Henderson:

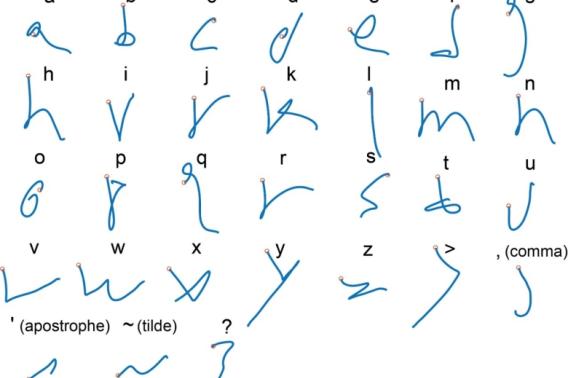

Yeah, so maybe I'll just start by emphasizing that this has been a lengthy process. Krishna and I started working together in 2006, and we started our laboratory in 2009. Since that time, we've been working towards better devices for restoring movement and communication for people. And we started off translating the work that he had done in the non-human primate lab. So that's arm reaches. So using arm reaches to direct a computer cursor. And so we were able to demonstrate that in our human research participants. The next stage was to try to address complex multi-joint movements, so things like handwriting. And then finally the next stage was to get to the speech decoding work that we've been recently doing. So just to emphasize that it's been a laborious, stepwise process making these systems better and better.

To address your question about the implants, these are devices that have actually been around a very long time. So these devices are silicon micro electrode arrays, they're of various different sizes, and they can come in various configurations. The electrodes themselves are one and a half millimeters in length and penetrate just into the outer layers of the cortex, the outer surface of the brain, and record electrical potentials from one or several neurons each. We then amplify those tiny signals, send them out through a pedestal, which is mounted on the skull, titanium pedestal with contact pads to which a pre-amplifier can mate. And then from there, they're sent to a computer where they're decoded.

Nicholas Weiler:

So the way I always picture this is it's sort of like a little square computer chip that has almost like a pin cushion, but very, very tiny electrodes. So they're just penetrating into the outer surface of the cortex. What's the size again? It's about the size of a postage stamp or is it a little bit bigger?

Jaimie Henderson:

It's smaller than that.

Nicholas Weiler:

Smaller than that.

Jaimie Henderson:

It's actually about the size of a pea. The electrode arrays are 4 millimeters or 3.2 millimeters square. They're quite small.

Nicholas Weiler:

Okay. So you've got this little sort of pea sized or fingernail sized implant that's sitting on the surface of the brain. What can you tell me about how that allows you to figure out what a person is trying to either point out on a screen letter by letter or more recently to actually translate the words that they're trying to say?

Jaimie Henderson:

So this is based on research that started back in the '80s demonstrating that this part of the brain, the precentral gyrus or motor cortex, encodes various different things including movement of individual joints or muscles, but importantly reaching directions or other complex movements of the upper extremity.

So we've used this knowledge that we can look at the firing patterns of those neurons and figure out what the intent of the animal or of the person is. And by correlating those two things, knowing that they're reaching toward a target and looking at the neural firing in this entire array, so dozens or hundreds potentially of neurons, we can quite accurately decode what that intended movement is.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's amazing. So you're basically, in a person who has the connections between their brain and their muscles have been severed or damaged or no longer communicating, you can just go into the part of the brain that would normally be controlling or participating in controlling those movements and just say, well, what's the brain trying to do?

Jaimie Henderson:

Exactly.

Nicholas Weiler:

So you had results a couple years ago allowing people to imagine writing letters by hand, which was really effective. And then you had another study this summer with patients with ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease that showed that they were able to communicate quite quickly via one of these devices. What is the state-of-the-art that you've been able to achieve?

Jaimie Henderson:

Well, currently in our laboratory and others we're achieving pretty good accuracy is although they could be better. So from 125,000 word vocabulary, which is pretty close to everything you'd want to say, we can get about a 25% word error rate. Now, that's still pretty high. That's one out of every four words wrong. But the fact that we can, with about 75% accuracy, figure out what someone is trying to say from their brain activity, we feel very encouraged by that proof of concept. It seems that the more inputs you have, the more electrodes you're recording from, the higher that accuracy can get. And we're quite confident that with more electrodes placed in these areas we'll get better and better accuracies to the point where these will actually become usable systems for people with communication disorders.

Nicholas Weiler:

That's fantastic. So before we move on I'd love to hear just a little bit more... I mean, we mentioned earlier that Krishna Shenoy has been your long time, a very close collaborator in this work. I'd love to hear a little bit about how you and Krishna complimented each other to advance this field. Krishna was trained as an electrical engineer. You're a neurosurgeon. How did your collaboration bring you to the frontiers of neuroscience?

Jaimie Henderson:

The collaboration with Krishna was truly a wonderful experience for me. We hit it off immediately when I interviewed at Stanford in 2004, and we both knew that we wanted to push this field forward. I've always been sort of a wannabe engineer, and Krishna always said he was a wannabe doctor. So we sort of completed each other that way. We worked practically every day to talk about strategy. We co-mentor all of the students in postdocs in the laboratory, everything was shared. And that shared vision that we developed together is the reason that our laboratory has come to where it is today. Was privileged to work with him, a real giant in the field, and his loss is sorely missed.

Nicholas Weiler:

Yeah, he's missed by all of us. And not only for his scientific brilliance, but I've spoken to many of his trainees and they all just talk about the support he gave to everyone. And as you say, has really been a giant in this field and building it, building all the people as well as the science.

I want to close by just reflecting on how amazing it is that we now have several different types of brain implants. We've talked about in one case, stimulating dormant brain circuits to restore function after brain injury, and in another case, reading out the language of the brain to allow people to communicate through a computer interface. And I understand that this is particularly personal for you because your father was in a car accident when you were very young and became paralyzed.

How does it feel for you now to be getting to a point where we can for the first time really start to do something for patients who've experienced brain injuries?

Jaimie Henderson:

When we were able to decode our participant's speech, she was able to produce intelligible words on a screen, I sort of felt like things had come full circle in a way. As you mentioned, my father was injured in a very bad car accident when I was five years old, and I grew up really wanting to understand what he had to say. He lost the ability to speak intelligibly. He was able to make sounds in some words. He was clearly still in there. He would make jokes and laugh uproariously and nobody could understand what the punchline was, even though he tried to repeat it over and over so that we would get it. And so it was something that as a young person was particularly frustrating to me not to be able to know my father. And so to me, this work has a lot of personal satisfaction in that ability to restore function to people who've lost it.

I think the battle against brain injury has to be fought on many fronts. Both the write-in and the readout are areas that have a great passion for restoring function. Whether it be through computer assistance, trying to decide what someone's thinking or trying to communicate, and then outputting that. But also on the restorative end with deep brain stimulation and other therapies to restore function from a stimulation standpoint. So I'm very excited about where the field is going in both of those expanding areas.

Nicholas Weiler:

Yeah, it must be very gratifying, you see this in your patients, you see this in the people that you're working to help.

Well, we're out of time. I would love to come back and talk more about this as more discoveries come out and as these clinical trials progress. Thank you so much, Jaimie, for being on the show.

Jaimie Henderson:

Thank you, Nic. It's been a pleasure.

Nicholas Weiler:

Thanks again to our guest, Jaimie Henderson. We'll include links for you to learn more about his work in the show notes. And if you're interested in learning more about the work of the late Krishna Shenoy, we've also included some stories speaking with his colleagues and trainees about his legacy.

If you're enjoying the show, please subscribe and share with your friends. It helps us grow as a show and bring more listeners to the frontiers of Neuroscience. We'd also love to hear from you. Leave us comments or give us a shout-out on social media. We're at Stanford Brain.

From Our Neurons to Yours is produced by Michael Osborne at 14th Street Studios with production assistance from Morgan Honaker. Our logo is by Aimiee Garza. I'm Nicholas Weiler at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University. See you next time.