By Mandy Erickson

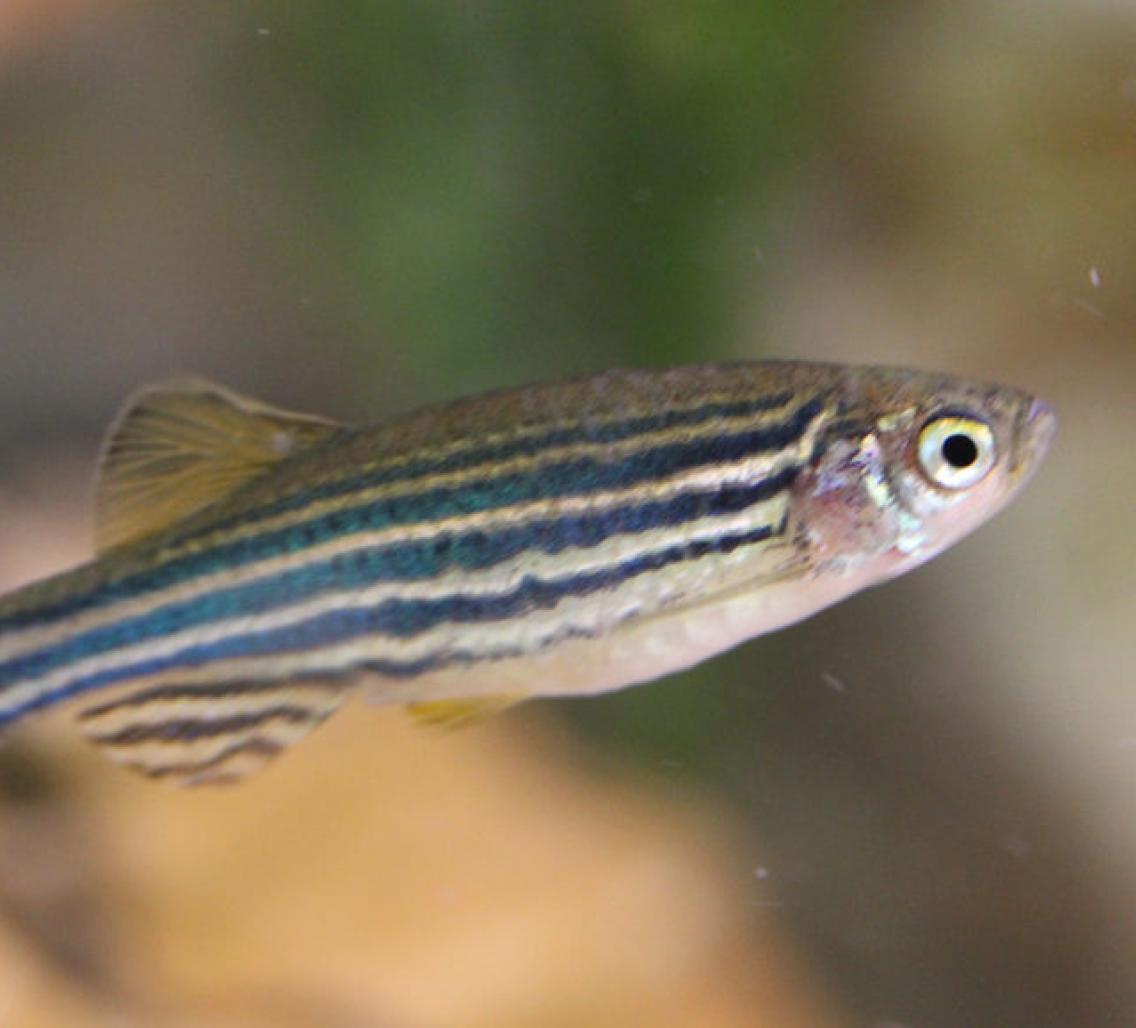

When night falls, most fish find a cozy spot -- on a patch of sand, under some coral, even in the open sea -- and catch some Z's. While researchers and aquarium owners have known about aquatic snoozing for a century, only now do we know that zebrafish and people display similar neural patterns while they sleep.

Stanford researchers have found that the freshwater zebrafish slumber much the way we do: They display a type of slow-wave sleep and a type of REM (also known as paradoxical) sleep. The discovery suggests that these neural sleep signatures -- present in mammals, reptiles and birds -- emerged at least 450 million years ago.

"The only real difference is a lack of rapid eye movement during paradoxical sleep," said Philippe Mourrain, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. (Zebrafish, native to South Asia and frequent lab subjects, also don't close their eyes -- they have no eyelids.)

Photo by Philippe Mourrain of a parrotfish sleeping in French Polynesia.

Their research appears on the cover of the July 11 issue of Nature.

Louis Leung, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar, built a benchtop scanning machine with a mini-aquarium to record the brain and body activity of young zebrafish. Using a petri dish, he transported his subjects from a basement room filled with plastic tanks containing thousands of the inch-long zebrafish to the machine in a lab two floors up.

He then pipetted the fish, one at a time, into the little aquarium containing water and agarose, which immobilizes them so they are perfectly positioned for the scan, and waited for them to find slumberland. They then applied fluorescent polysomnography which they invented.

Their discovery could help researchers develop sleep-inducing medications and study other aspects of sleep. Neural sleep abnormalities are believed to be partly responsible for cognitive and behavioral impairments in neurodevelopmental and degenerative disorders, including autism, fragile X syndrome, and Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

The finding may also open the door to more sleep research. Zebrafish are less expensive to care for than mice are, and it's easy to administer medications: You just add the drug to the water.

As research subjects, Leung said, "Mice aren't perfect because they're nocturnal. From a circadian standpoint, the diurnal zebrafish is more biologically in phase when you're comparing fish to humans."