New voltage indicator enables ultra-sensitive synaptic imaging

Bioengineers and neuroscientists at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University have developed a highly sensitive tool for detecting brain cells’ subtlest electrical signals.

Published in the November 2024 issue of Neuron, this breakthrough allows scientists, for the first time, to visualize the full spectrum of electrical communication between human brain cells in real time. This dramatically enhances researchers' ability to understand brain signaling and the abnormalities linked to disorders such as autism and epilepsy.

Every sensation, memory, and thought we experience is encoded in the flickering signals that ceaselessly course through our brain's vast neural networks. Neurons "hear" these electrical whispers, their broad-branching dendrites intercepting messages through synaptic connections from thousands of informants. Each message, passed encoded in a packet of chemical neurotransmitters, triggers a tiny electrical response at the synapse — a few thousandths of a volt or less, fading away within milliseconds. Most of these are barely perceptible by the cell. But dozens of overlapping messages can add up to something meaningful, triggering a roughly 100 millivolt "spike" or "action potential" that the cell passes along to all its contacts in the network, distributing its own cascade of chemical messages, and continuing the electrical flux that, for example, allows you to read this sentence.

A challenge for neuroscientists since the first half of the 20th century has been how to detect these tiny signals, to decode the electrical language of the brain. Neuronal spikes, and eventually the tiny “synaptic potentials,” were first detected using ingenious advances in recording electrodes and preparations of isolated neurons and brain slices. But neuroscientists have long desired reliable ways to visualize the full spectrum of electrical flux of active brain circuits in real time — ideally in the human brain.

The new research makes this possible for the first time with a new genetically encoded voltage indicator called ASAP5, the latest in a family of cutting-edge voltage sensors developed by Stanford chemical engineer Michael Lin, an associate professor of neurobiology and bioengineering and member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

A new level of sensitivity for studying synaptic activity

The new advance builds on a foundational collaboration between Lin and computational biophysicist Ron Dror, the Cheriton Family Professor of Computer Science in the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab, which was catalyzed by a Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute seed grant in 2017. That work was critical to developing ASAP5’s predecessors, ASAP3 and ASAP4.

These tools — and others developed by other laboratories — have become common means of observing electrical activity in cultured neurons and the brains of animals such as mice and flies. But these tools have so far been limited to detecting neuronal spikes and larger “subthreshold” synaptic signals. Getting to the level of sensitivity needed to detect even the quietest whispers of synaptic activity had remained a challenge.

“The unsolved problem was that voltage indicators haven’t had the sensitivity to detect individual synaptic events reliably in neurons, and haven’t been used to look at signaling between human neurons,” said Lin, the study’s senior author.

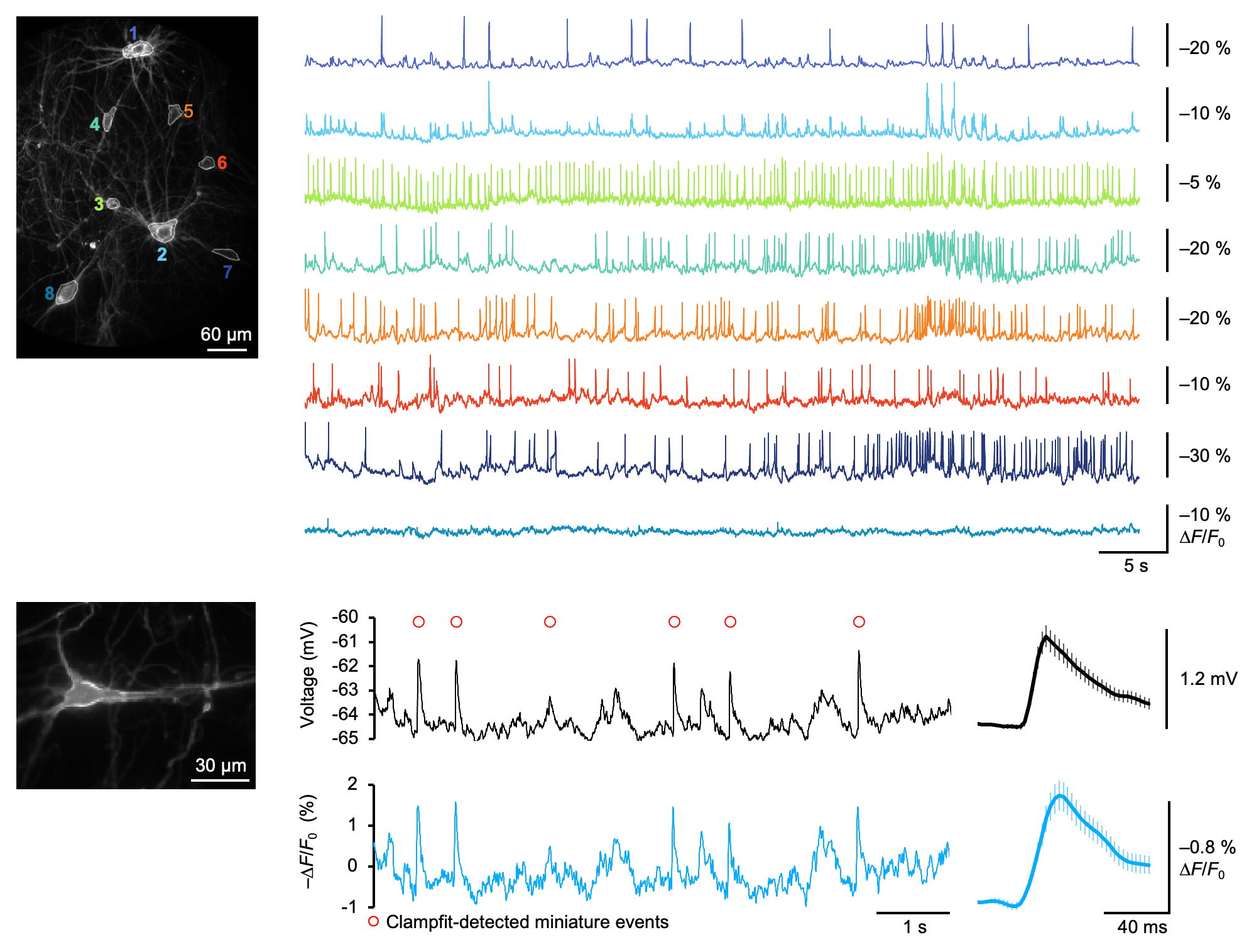

The new study found a solution. By screening thousands of genetic variants, the team engineered an ASAP molecule optimized to detect voltage changes specifically around the normal resting voltage of neurons. With the resulting sensor, researchers were able to detect even the random spontaneous release of individual packets of neurotransmitter — the smallest possible synaptic signal.

“Because of ASAP5’s improved sensitivity and speed, we can detect the small electrical impulses induced by the reception of single synaptic vesicles either locally at the synapse or at the cell body. This gave us the ability to observe how these impulses propagate from the synapse to the cell body,” Lin said.

Insights into neuronal signaling

These advancements not only address long-standing challenges in voltage detection but also enable new discoveries in how neurons communicate through these subtle electrical signals.

The tool has already allowed the research team to make new observations about how cells sum up the messages from their most far-flung informants. “Fascinatingly, we found that synapses that are farther away from the cell body initiate larger responses,” Lin explained.

In other words, neurons tune the most distant synapses on their extensive dendrites to be electrically “louder” so their input is not drowned out by synapses closer to the cell body.

Promise against neurological disease

ASAP5’s ability to detect synaptic potentials caused by the spontaneous release of single neurotransmitter packets — often referred to as synaptic “noise” — is not only an impressive marker of its sensitivity but may have important uses in studying neurological diseases.

Various disorders of the nervous system — from autism to epilepsy — involve changes in the basic properties of synapses, and so enabling scientists to observe the smallest whispers of synaptic signaling will be a valuable tool for scientists to understand, diagnose, and eventually treat these disorders.

The research team tested the tool across multiple common laboratory preparations and model organisms, including lab-grown human brain cells.

“We established that we could detect synaptic events in human neurons derived from human stem cells, and we could visualize coordination between multiple human neurons, opening up the possibility of rapidly assessing how mutations associated with disease affect the activity of synapses and the ability of neurons to fire within networks,” Lin said.

The work was done in collaboration with Tom Clandinin, Tom Südhof, Jun Ding and Marius Wernig at Stanford, and with Ed Boyden (MIT), Na Ji and Dan Feldman (Berkeley), Peyman Golshani (UCLA), and Stéphane Dieudonné (École Normale Supérieure), and was funded by the NIH BRAIN Initiative. The two co-lead authors were PhD student Alex Hao and postdoc Sungmoo Lee.

The role of NIH BRAIN Initiative in technology development

Lin emphasized the importance of the NIH BRAIN Initiative, which faced significant cuts in the latest NIH budget: “BRAIN has been absolutely critical to our efforts developing fluorescent voltage indicators. The majority of our funding for voltage indicator development has come from BRAIN, with an early Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute seed grant and an earlier NSF grant being the only other sources.”

Lin gives credit to the vision of Wu Tsai Neuro founding director Bill Newsome and Cori Bargman of Rockefeller University, who led the BRAIN Initiative study group in 2014.

“BRAIN supported technologies that would improve our ability to understand the different connections and cell types in the brain, and to record from and manipulate these populations, whether optically or electrically or molecularly,” Lin said. “BRAIN was unabashed in putting technologies first and marking progress in terms of quantifiable technical abilities, but the program officers and reviewers also made sure that technologies were not operating in isolation but were paired with neurobiologists who wanted to use the tools to generate new discoveries related to how neurons calculate or represent particular behaviors or decisions. With fluorescent voltage reporters, I think we are now making that transition from technology improvement to widespread use in the community.”