By Peggy Guey-Chi Chen

September 2008

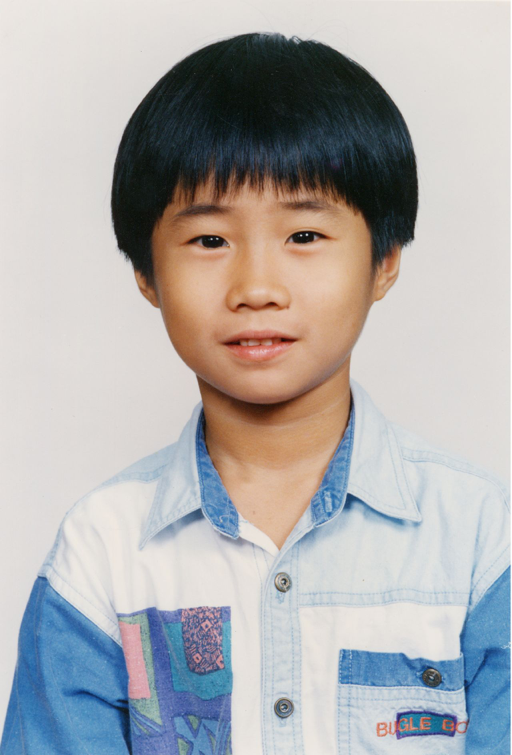

I can hardly recall a childhood memory that does not include my cousin, Sammy. On his first visit from Taiwan, when I was seven years old, his mother inexplicably charged me with finding a suitable English name for him. I immediately thought of my favorite toy, a stuffed penguin named Tuxedo Sam. My sister and I anticipated his visits eagerly and mourned his departures ferociously. He was more kid-brother than cousin, and we adored him even as we tormented him. He was earnest and bookish, sensitive and playful.

During his visits, I would come downstairs for breakfast to find him sitting, legs dangling under the kitchen table, reading about world events with great seriousness while singing along absentmindedly to the radio. My sister and I once told him that his McDonald’s consumption was burning a hole in the ozone layer. Later that night we found him clutching his bed covers, staring wide-eyed at the stucco ceiling. When we asked what was bothering him he whispered conspiratorially, “the ozone layer.” In high school when my parents and I disagreed over my choice of college, it was 10 year-old Sammy’s voice on the phone, telling me he had looked up college rankings and thought all my choices were good. When I backpacked through Europe in college, Sammy wanted coins from all the countries I visited, and I obligingly dragged a heavy jar with me, gradually filling it with coins that Sammy would pour out onto a table halfway around the world and marvel at.

In the fall of my senior year of college, as I weighed the pros and cons of various English Literature graduate schools, my aunt called to say that Sammy had suffered a seizure and the doctors suspected he might have epilepsy. No big deal, I reasoned, a good friend in high school had epilepsy and he took medication and was fine. One MRI and two lumbar punctures later, we all wished it was epilepsy. Sammy’s disease had such large words and I, immersed in Milton and Joyce, understood none of them.

So I did what I had been taught to do—what I had always been good at. I read, I asked questions, I did everything I could that might help me understand. Before long, it became terrifyingly clear that Sammy would leave us. Moreover, Sammy’s disease was hell-bent on stripping him of every last scrap of dignity before snatching him away, and there was nothing we could do to change this destiny.

Lost and confused, I abandoned the familiarity of plot lines and historical allusions to study mechanisms of disease and viral infectivity. I could postulate on how the causative virus gained access to a “suitable host” like Sammy. I could tell you in excruciating detail which proteins triggered which immune system reactions and how these components all came together in a diabolic assembly line to wreak havoc on Sammy’s nervous system. I could describe the epidemiology and tell you who was more susceptible. But I couldn’t save Sammy. And the closer I came to understanding his disease, the more I knew that my true questions had nothing to do with the pathophysiology and everything to do with the unanswerable: why did this have to happen to Sammy?

This led me, somewhat circuitously, to medical school. I thought about Sammy a lot during this time. His illness informed every course I enrolled in, from the basic sciences to public health. I obsessed over measures that might have prevented his illness, and was bewildered by the political processes that allowed such catastrophic events to occur. In the end, I chose to specialize in pediatrics, which came as a surprise to those who knew me. I liked children well enough, but was not particularly drawn to them and was never naturally comfortable around them. I was never a pediatrician in the Norman Rockwell mold, and was woefully ill-equipped when I started my training. For the entirety of my first year of residency, everything I knew about breast-feeding I had learned from a senior resident—a male senior resident who had no children. Where my colleagues were well versed in developmental stages and a wide range of pediatric ailments, I started my training extremely knowledgeable about one very specific neurodegenerative disease and, frankly, little else. There would be time and occasion to learn about these things, I would find.

In hindsight, it is painfully obvious to me that my experience and my decisions were the result of the classic wounded-doctor cliché: perhaps if celestial order were restored, if children who were sick were made well, the heavens would see fit to give Sammy back to me. I also suppose that working with sick children, whose illness were often the result of a multitude of cosmic misfortunes, allowed me to feel a certain bond with them, forged by shared tragedy. But there would be no sharing on my part in this setting. I could step into their tragedies: express my hope that they would find peace in their ultimate decisions, but they could never be allowed to venture into mine. I had been well-trained to keep my personal life out of my professional endeavors, and so I never spoke of Sammy with any of my colleagues, my patients or their families, not even in the abstract. I told myself it would be selfish to supersede other people’s heartbreaks with my own.

It would, however, be disingenuous to suggest that my motivations were completely selfless. At the heart of this decision was a sense of self-preservation. I had shared once and only once in a professional setting, with a medical school dean who had responded to my tentative revelation with a callous comment about Sammy’s impending and inevitable death. I had quickly and awkwardly excused myself from the meeting and wept for hours in a dingy stairwell. The encounter had made me feel weak and vulnerable in a place where I needed to be in control and I would not, could not, make that mistake again.

Sometimes I had the nagging notion that I was asking families to make decisions in black and white while I continued to occupy the spaces in gray, and that seemed somehow unfair. Occasionally, especially after caring for a particularly ill child with a chaotic home life, I would think to myself with a sense of poetic justice that if this awful thing had to happen to someone, at least it happened to Sammy who was lucky enough to have people in his family who loved him and could take good care of him. And even as the thoughts came spilling out, I would taste their bitterness and know that I didn’t mean a single word.

Years after his diagnosis, despite being permanently bedridden, his achievements steadily surpassed by his younger brothers, I still looked at Sammy and thought only of my happy-go-lucky little cousin. I understood cerebrally that in many ways his continued existence was more for us, his family, than for himself. I could even make the intellectual argument when I needed to, but emotionally I could not often find my way to that place. I hoped he wasn’t scared and I hoped he didn’t feel any pain, but to have him alive in even the most nominal sense of the word and to be able to keep the faintest glimmer of hope for some sort of meaningful recovery was better, in many ways, than letting him go and losing that hope. I and my family were cursed by our memories of the life that Sammy was meant to have.

He left us quietly one afternoon in October. I was in Zambia, working in a hospital in the shadow of Victoria Falls. The news came by e-mail one morning, and the world became suddenly smaller and darker. One thirty-six-hour flight later, with my luggage stranded somewhere between Johannesburg and Taipei, I said goodbye to Sammy for the last time. I was, in the end, surprised at how grateful we all were to finally do what we had dreaded for so many years.

For me, he is forever frozen in time at the age of twelve, with his head thrown back, laughing. And as his younger brothers outgrow him one-by-one, reaching milestones—high school, girlfriends, college, first jobs - an aching sense of loss returns to mourn a life that I fully expected to be a part of.

The machinery of life continues to patter merrily, obliviously, along. My husband and I are expecting our first child in the fall. We find ourselves thinking, hoping, dreaming for this tiny person who, by the time of his or her birth, we will have loved already for nine months. Thinking about Sammy, his life, his illness and his death in the context of becoming a parent myself has put a new lens of pain on a wound I had considered to be scarred over. I think about how much Sammy would have loved a little niece or nephew, and wonder how to let this little person know what a beautiful soul Sammy was.

These days, the finer points of Sammy’s disease and his illness have become blurred—like an old friend whose face I am unable to recall in detail. At some point, my line of sight shifted from a microscopic examination of Sammy’s disease and which factors triggered which immunologic effects, to what it means to love someone who was so sick for so long. Around the same time, my personal anger transformed into anger at global inequalities that result from nothing more than accidents of birth. I know that Sammy and his illness guided me to where I am and what I do today. I love my work and can think of nothing else that would fit my interests and abilities quite so well. It has allowed me experiences and insights that I could not be privy to in any other profession.

But even now, without hesitation, I would give up everything to make the devil’s bargain and have Sammy back instead.