By Nathan Collins

Most of us take it for granted that we can sense where our bodies and limbs are, even in the dark. Yet scientists don’t know exactly how that sense, called proprioception, works. Now, Stanford mechanical engineers are working to better understand proprioception — in the hope of one day helping people for whom sense has been impaired by stroke or other diseases.

To better grasp what proprioception is and why it’s so important, try this: pick an object near you, close your eyes and reach out to grab it. Chances are you’ll be a little bit off, maybe half an inch, but you won’t have too much trouble. But for many people who’ve survived a stroke, things are more difficult — if the stroke affected parts of the brain involved in sensing movement, they might struggle to reach for objects even with their eyes open.

Yet to understand those more serious deficits, mechanical engineering graduate student Sean Sketchsays, he had to take a step back: Even in healthy people, “proprioception is still really poorly understood,” compared to other senses.

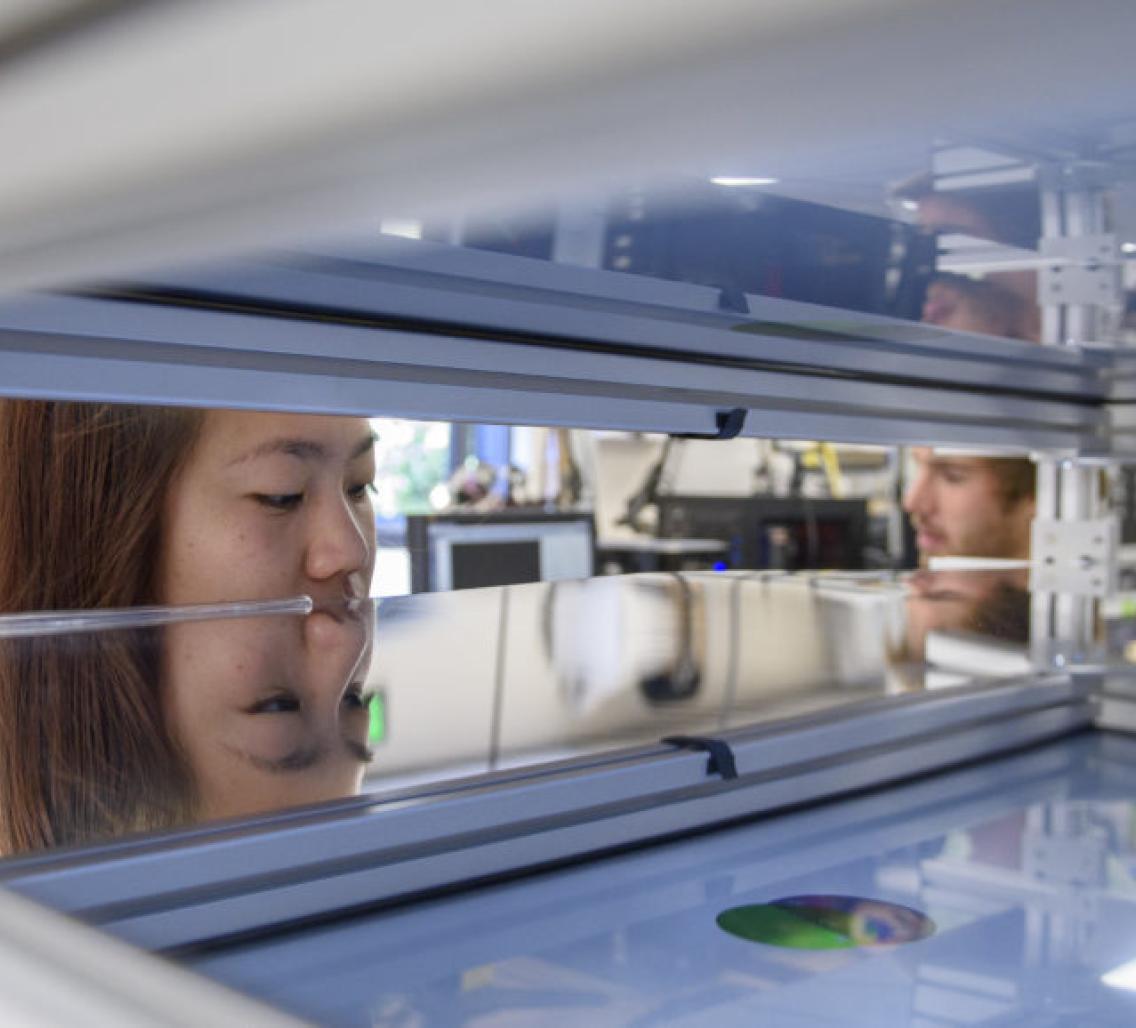

To address this problem, Sketch and colleagues built a sort of desk that sits above a person’s arm (shown in the photo above), so that the person can feel but not see when they move. Below the desk, the person’s arm sits in an exoskeleton outfitted with sensors to track its position. And on the desk, Sketch can project virtual objects. By asking a person to reach for these virtual objects at particular positions, and tracking where they actually move their hands, Sketch is able to quantify the errors in their proprioception — that is, how far their hand actually is from where they believe it to be.

So far, he’s used the desk to investigate how accurately and precisely healthy people can sense arm position with proprioception alone, as well as the nature of errors that people make — for instance, it turns out that people are generally better at estimating the left-right and front-back position of their hands than the rotation of their shoulders and elbows.

But those results, presented last March at the 2018 IEEE Haptics Symposium, are really just the baseline against which Sketch and his advisor, Allison Okamura, PhD, a professor of mechanical engineering and member of the Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Neurosciences Institute, will compare stroke survivors.

“Everybody has proprioceptive deficits,” Sketch says. “We’re all off by a little bit, but in stroke patients, the understanding of space is warped and biased a little bit more.”

The team is looking at a number of possible ways stroke patients’ proprioception differs from others’ — because, after all, there are a lot of ways people can move. Sketch says it’s time to start figuring it out, so that they can intelligently design tools that will help people who’ve had a stroke. “Ultimately, the nature of the deficits will influence the design of rehab therapies and assistive devices,” Sketch says.