From how we form memories to what drives addiction: A conversation with Robert Malenka

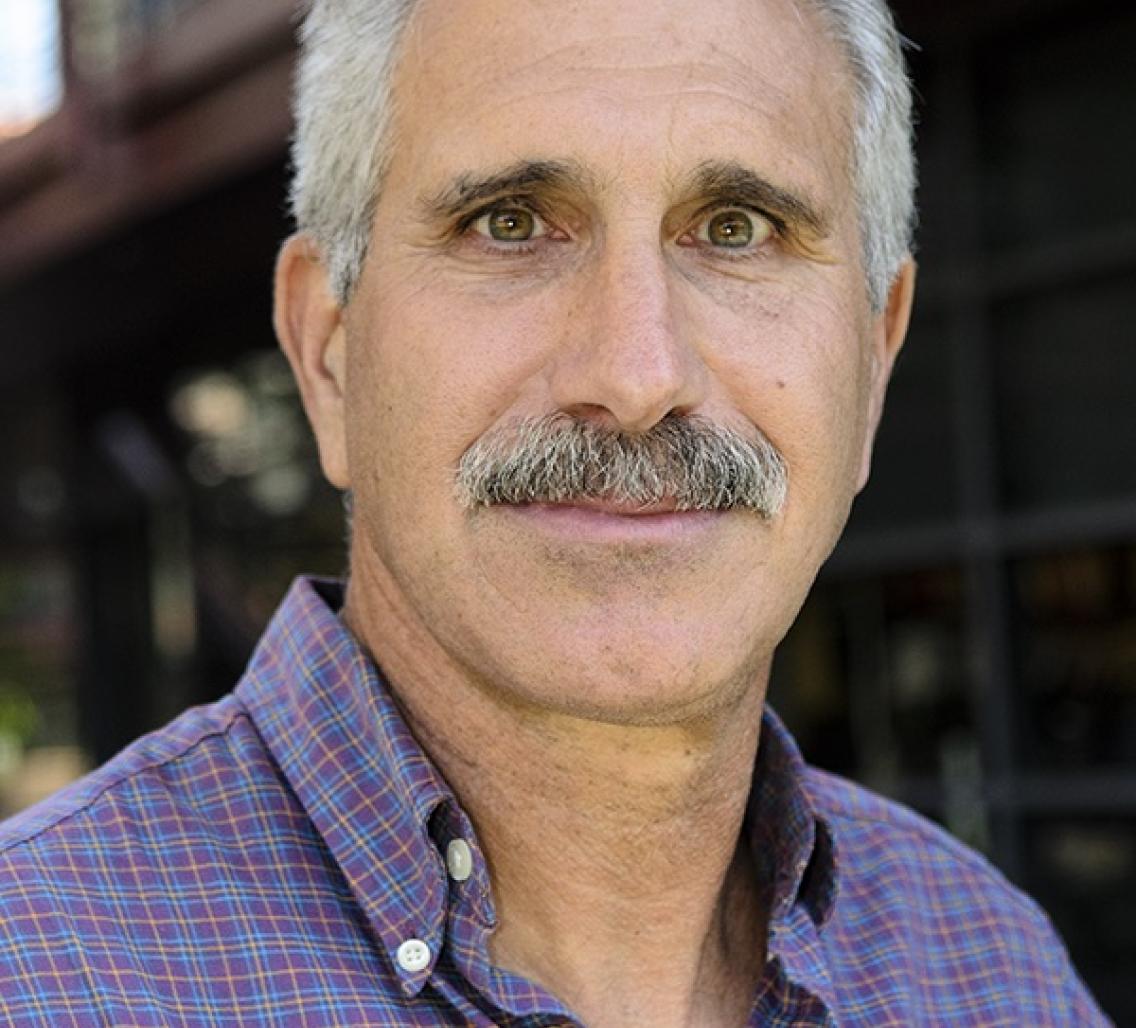

Robert Malenka, the Nancy Friend Pritzer Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, is famous for his discoveries on how neurons in our brain make and store new memories. He is also a pioneer in the field of addiction research, and an executive committee member of the Stanford Neurosciences Institute.

Graduate student David Lipton recently talked with Malenka about his memory and addiction work and what excites him in the future of neuroscience research.

How do we make new memories?

Memories are the product of physical changes that occur in our brains. Nerve cells in our brains called neurons talk to each other via physical connections called synapses. At the synapse, one neuron does the ‘talking’ and one neuron does the ‘listening.’ It turns out that it is possible to tune the volume of the conversation between a pair of neurons at each synapse in the brain. We think that memories form when a set of synapses is made louder or more powerful—a phenomenon called long-term potentiation, or LTP.

How was long-term potentiation (LTP) first discovered?

A Canadian psychologist named Donald Hebb first proposed the idea that synapses that “fire together, wire together.” This essentially means that the synaptic connections that are used the most get strengthened the most. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that researchers showed experimentally that synchronous activity between a pair of neurons could increase the strength of synaptic communication between them, a phenomenon we now call LTP.

More specifically, it was shown that if neuron A sends a flurry of messages to neuron B right before neuron B’s message-sending activity is similarly heightened, then the neuron A to neuron B synapse will be strengthened. In a brain region called the hippocampus, which we know to be important for memory formation, this LTP-induced increase in synaptic strength could last for days or even weeks.

How does long-term potentiation work? If you are a neuron, how do you sense this synchronous activity?

As a post-doc in Roger Nicoll’s lab, I found that during long-term potentiation, Calcium ions rush into the neuron receiving messages – neuron B in the prior example - and activate a protein called Cam Kinase II. This finding proved to be really exciting because it reduced the initiation of LTP to the action of specific ions and proteins.

Then, after my post-doc, I started my own lab, and I noticed an abstract by my friend Mark Bear about the opposite phenomenon, called Long-Term Depression, or LTD. In LTD, asynchronous activity at the synapse causes a long-lasting decrease in the strength of synapses. With Mark’s blessing, I published several papers showing that LTD was activated by a protein that plays the opposite role inside the neuron as Cam Kinase II.

So you have LTP and LTD as seemingly opposite phenomena at synapses, and they rely on proteins that have opposite roles inside the cell. This allows you to turn the volume of synaptic communication up or down, giving you bidirectional control of synaptic strength. People liked the story – because it made sense. It was a very satisfying hypothesis.

How does this signal inside neurons ultimately change the volume of the communication between two neurons?

Well, I read a paper that proposed the existence of “silent synapses” in neurons—synapses with their volume turned all the way down. Now, we knew that there are certain channel proteins called AMPA receptors, which are essential for listening to the messages sent by other neurons. It could be that silent synapses are synapses missing these channel proteins, making them deaf to the messages being sent to them.

When I saw this paper, bells and whistles went off in my head. By increasing the number of ‘ears’, or AMPA receptor proteins, at the synapse, you could essentially ‘hear’ a louder message being relayed across the synapse even though the volume of the actual speech has not changed. I vividly remember reading this paper and then saying “Oh my God! We have got to start working on this!”

So I teamed up with my post-doc mentor Roger Nicoll and cell biologist, Mark Von Zastrow and showed that AMPA receptors can in fact move into and out of synapses. If we prevented them from moving into synapses we could block LTP, and if we prevented them from moving out of synapses we could block LTD. So, it all came together – it all made sense: When AMPA receptor proteins move into synapses during LTP, you get a stronger synapse, when they move out of synapses during LTD, you get a weaker synapse.

Okay, so is long-term potentiation the mechanism our brains use to make new memories, and is long-term depression a description of what happens when we forget them?

I no longer think it’s useful to think of LTP simply as a memory mechanism and LTD simply as a forgetting mechanism. I view LTP and LTD as being fundamental properties of synapses that allow neural circuits in the brain to be modified in response to experience, and ultimately to change how we behave. So you have to define your question more precisely; you have to ask: “at this specific set of synapses, what do LTP or LTD do?” Or how do LTP and LTD contribute to this particular behavior?

So, what’s a good example of a behavior that LTP and LTD underlie?

Well, my lab has focused on the role of LTP/LTD in models of a variety of brain disorders including addiction, which, as a psychiatrist, I have always been interested in. Antonello Bonci, who was then a post-doc in my lab, and I published a series of influential papers that showed that giving animals drugs of abuse like cocaine caused LTP-like changes at the synapses on dopamine neurons in the midbrain that are involved in pleasure or rewarding behavior. We also showed that these same drugs caused an opposite, LTD-like change in neurons in the Nucleus Accumbens, another key part of the brain’s reward pathway. When you reverse LTP and LTD using a fancy technique called optogenetics, then you no longer see an animal’s behavior change so drastically after being given these drugs; they no longer exhibit certain addiction behaviors. It’s amazing. Over the years, neuroscience has gone from discovering key principles of how learning occurs at synapses in the brain, such as LTP and LTD, to being able to pinpoint some of the behavioral changes in addiction to the modification of a specific population of synapses in the brain.

What are you most excited about for neuroscience in the near future?

As a psychiatrist, relating the basic research taking place in my lab, and in the field as a whole, to improving the human condition and treating disease is something I’m incredibly excited about.. This is one reason why I’m such a big supporter of the Stanford Neurosciences Institute. The institute plays a critical role in translating basic discoveries to improved treatment of human neuropsychiatric disorders by supporting collaborations between neuroscientists at Stanford who are tackling a particular problem, such as addiction or depression, from different perspectives.