Q&A: Linking sleep, brain insulation, and neurological disease with postdoc Daniela Rojo

As a child growing up in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Daniela Rojo spent many hours exploring the abundance of plants and insects that lived in her backyard. Her curiosity often led her to investigate the bugs, squishing them between her fingers to find out what was inside. Thus, from a very young age, Rojo sought to understand how biology gives rise to life in its many forms. By the time she took her first biology class in high school, Rojo’s dream to become a scientist had already firmly taken root.

That dream soon evolved to focus on becoming a neuroscientist once she began reading the work of Oliver Sacks, the late British neurologist and author. When Rojo learned about the ways that disruptions to the activity of tiny molecules in the brain can lead to large changes in neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration, she was hooked. Her Ph.D. work at the Institute of Research in Genetic Engineering and Molecular Biology in Buenos Aires examined how neurons in the brain’s arcuate nucleus regulate food intake and energy expenditure, and how abnormal gene expression in these cells can lead to obesity.

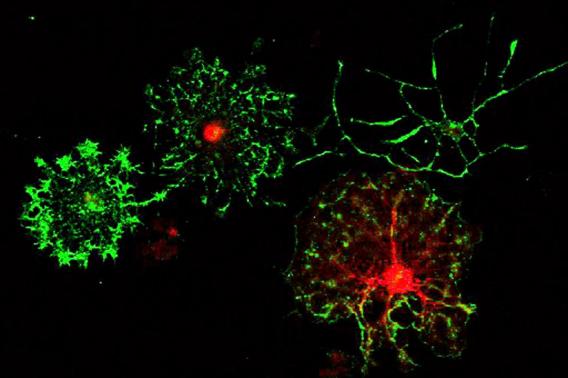

Now, as a postdoc supported by the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience at Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Rojo has returned to her early interest in how changes at the molecular level can cause damage in the brain. Working in the lab of Erin Gibson in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, she looks at how abnormal changes in gene activity impact the cells involved in producing myelin — the fatty casing that surrounds nerve fibers and enhances their conduction of electrical activity — to the extent that it leads to neurodegeneration in the brain.

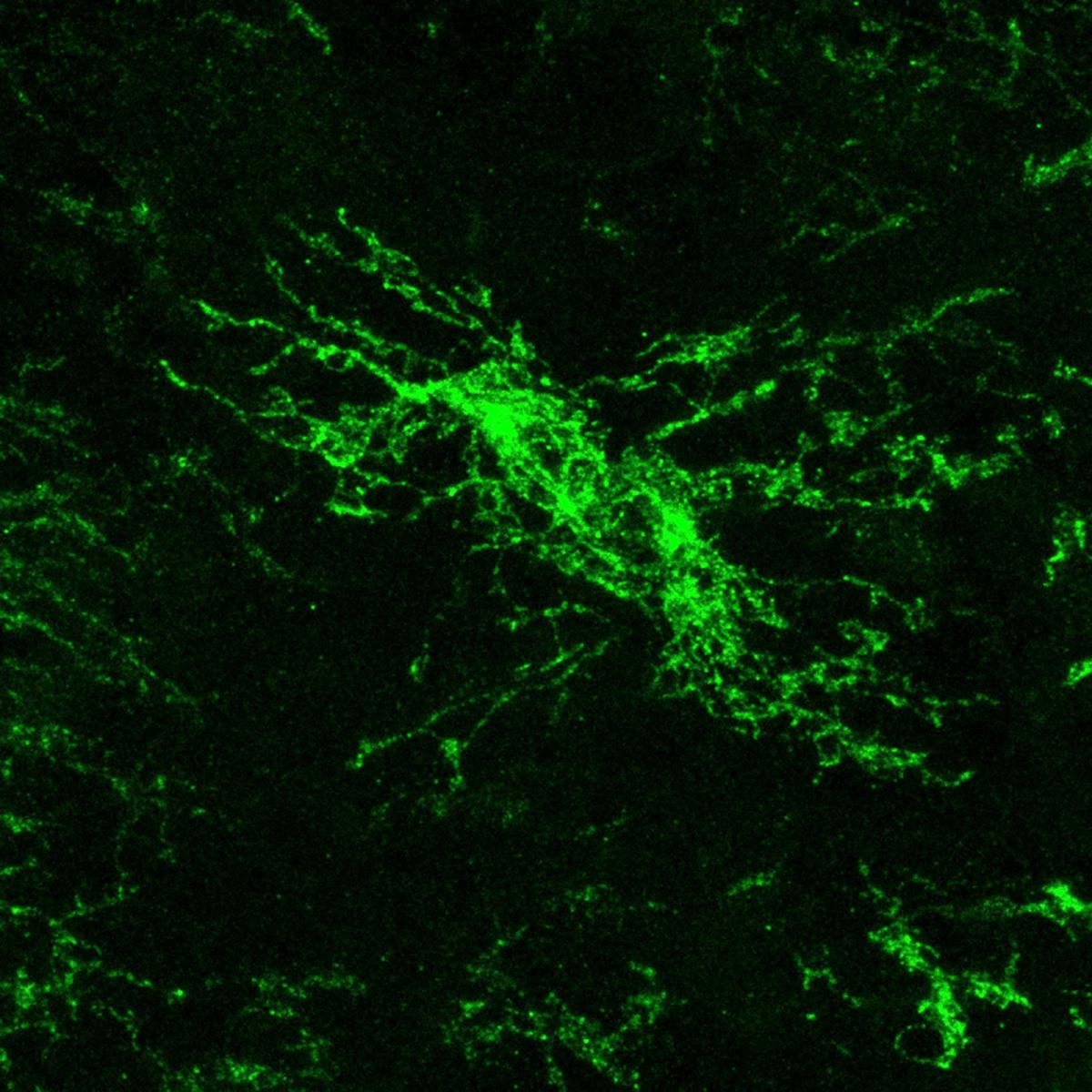

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) in vivo. Image by Erin Gibson.

We spoke with Rojo to discover more about her work and interests as a scientist, her experience as a member of the first cohort of Brain Resilience Scholars, and her goals for the future.

What led you to come to the U.S. for your postdoc to work with Erin Gibson?

I realized two things by the end of my PhD. First, that I was interested in understanding transcriptional regulation in the brain and how disruptions in those processes could lead to neurological disorders. And second, that I wanted to focus on neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders rather than on the processes that control appetite and energy expenditure like I studied during my PhD. I wanted to study disorders like autism spectrum disorder or multiple sclerosis, with a focus on understanding regulation of gene expression. And that requires cutting-edge methods that are very expensive. Working with these techniques in Argentina is quite challenging due to economic constraints. So, the U.S. and particularly Stanford — because of the collaborative environment and the access to the best technologies and research environment — was the perfect spot for me to grow in my scientific career.

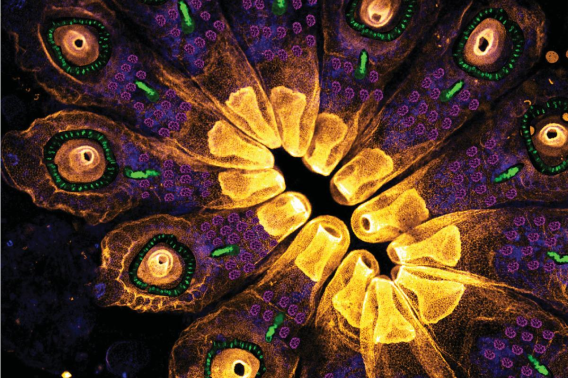

I came to Erin's lab to study links between circadian biology and the formation of myelin — this fatty structure that surrounds neuronal axons and enhances their communication — and how the disruption of those mechanisms could lead to neurological disorders.

Aberrant myelination is a common problem that many neurological disorders share. Interestingly, many of these disorders also have high levels of disturbances in sleep or circadian biology. But there is a gap in our knowledge about how circadian biology and myelin biology are connected. We don't understand how those interact in a healthy brain, and even less so how disruptions in these processes can lead to neurological disorders.

Why do you focus on the regulation of myelin instead of the more common focus in the neuroscience field on how myelin affects neuronal signaling?

In general, in neuroscience and sleep research, there's a lot of focus on understanding how neurons work, but not so much about how glia contributes to the efficient communication between the different nuclei in the brain. In the last decades, there has been more interest in these other cells of the brain and how they support neuronal signaling. Understanding how oligodendroglia are regulated is very important because half of the human brain is composed of white matter tracts, but we don't know completely what controls their dynamics.

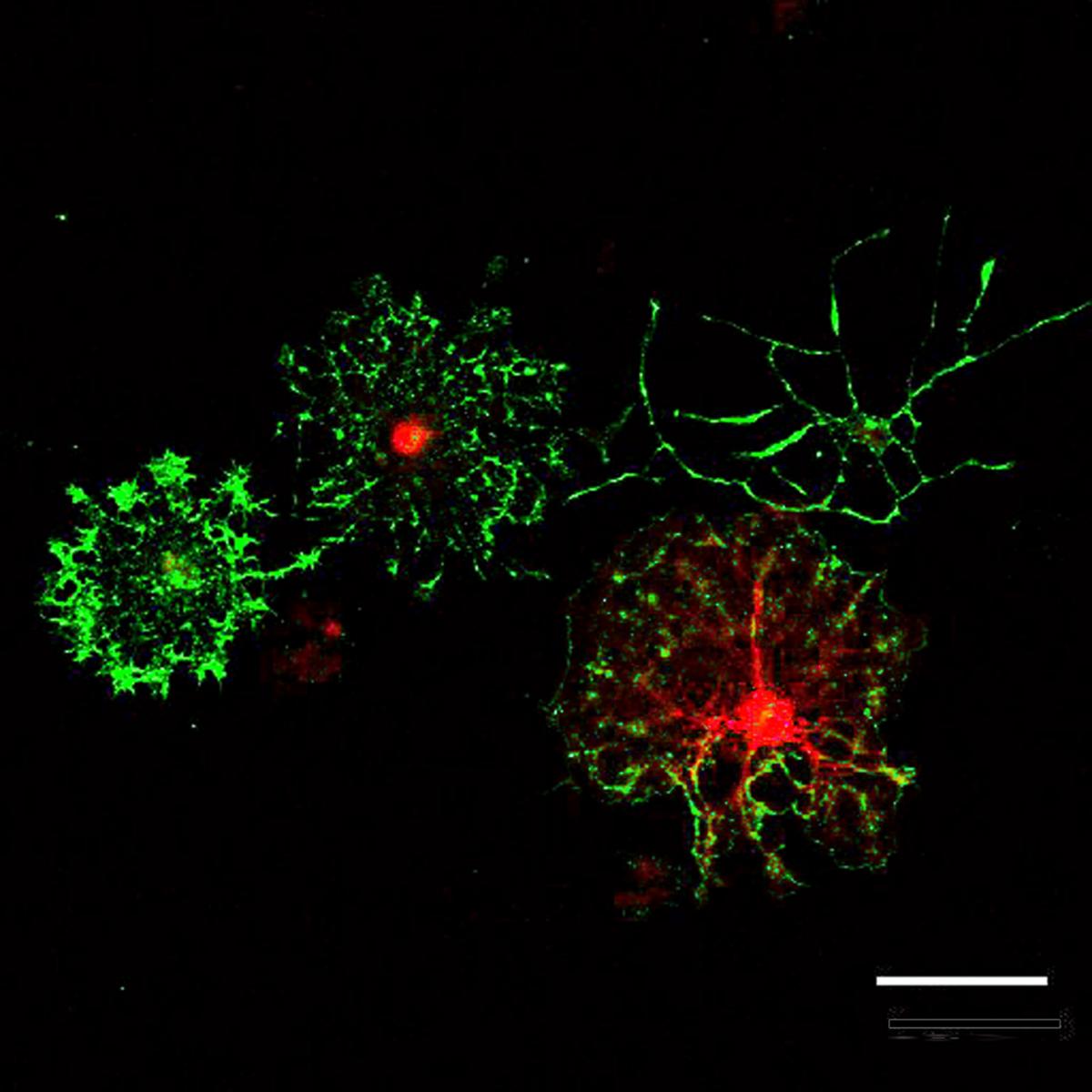

We focus on how the cells that give rise to myelinating cells function because this is a dynamic population of cells that is very evenly distributed throughout the brain. They go through the cycle of cell division and have a very tight regulation, but they can also differentiate to a mature cell that will produce myelin. These are fantastic cells, but we don't know much about them. If we can understand how these cells proliferate and differentiate, this would eventually help us design direct targeted therapies, for example to treat multiple sclerosis, a demyelinating disorder, where it will be very important to develop a therapeutic to restore myelin.

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) that the Gibson lab cultures in vitro and differentiates into myelinating oligodendrocytes. Image by Erin Gibson.

What has your experience been like being a Brain Resilience Postdoctoral Scholar?

I became a Brain Resilience Scholar at the beginning of this year, and it has been amazing. They have provided a great support system integrated with Wu Tsai Neuro’s longstanding Interdisciplinary Scholars postdoc program. We meet monthly and we have meetings where our mentors help us decide our paths. We have created a community of postdocs where we are all working in neuroscience but using different techniques and different approaches. I find that meeting in person each time allows us to generate more collaborations. Also, I couldn't be working without their financial support, and that has been very important for me, too.

What drives you as a scientist?

I think what drives me as a scientist, but also just as a person is to try to understand how things work. I've always been super curious, and I want to study what are the mechanisms that regulate cells, and eventually try to modify them to be able to design therapeutics. Really, it's these questions —what makes a cell different compared to another cell in the brain, how the brain controls this and how we can control it — it's just a deep curiosity for me. I will always be interested in understanding the mechanisms that make us special and unique by studying the brain.

That sounds very similar to how you played in your backyard as a child being led by your curiosity, right?

Yes, but with better techniques and more knowledge. I'm not just smashing bugs anymore!