Young cerebrospinal fluid may hold keys to healthy brain aging

In the past century, modern medicine has helped drive up average life expectancy in the United States and other developed countries by equipping doctors with the tools and know-how to manage our blood pressure, vaccinate us against dangerous viruses, swap out malfunctioning body parts with prosthetics or transplants, and much more. Unfortunately, though, modern doctors have little recourse when aging takes its toll on the brain.

Now, with a new study published in Nature, researchers at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute are helping to show that the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes our brains holds clues to healthy brain aging, a major focus of the new Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience anchored at Wu Tsai Neuro. Young CSF, they found, could improve memory and cognition in older mice, through effects on the development and function of oligodendrocytes, brain cells that wrap neurons in a fatty, insulating sheath, called myelin, which helps them send long-range signals. The findings open the door for potential new therapeutic targets for aging-related brain diseases like Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“This study shows that there’s something in young CSF that can make the brain function better,” said Tony Wyss-Coray, the senior author of the new paper who is D. H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences at Stanford and director of the Knight Initiative. “We’ve also started to pinpoint which components of the CSF are responsible for the improvement.”

Read our recent Q&A with Iram, who is a Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Scholar.

The research was led by Tal Iram, a Wu Tsai Neuro interdisciplinary postdoctoral scholar in the Wyss-Coray lab. Iram was inspired by previous experiments showing that blood transfusions from young mice had positive impacts on neurons in the brains of aged mice. She and colleagues mimicked this approach but swapped blood out for CSF.

Study lead author Tal Iram collected tiny samples of cerebrospinal fluid from mice to study its effects on brain aging.

Photo credit: Avery Krieger.

CSF, which is partially comprised of components from the blood and fully replenished four to five times daily, is responsible for nourishing the brain, removing waste products and helping to distribute signaling molecules, in addition to cushioning the brain inside our skulls. Previous research has shown that CSF’s contents change as we grow older — factors that promote cell growth begin to dwindle and inflammatory proteins that can be harmful increase in number. Considering the fluid’s intimate contact with the brain, Iram reasoned it might be the perfect place to look for factors that could foster healthy brain aging.

“With CSF we’re looking at the actual substance that the brain is exposed to,” she said. “It’s very different from blood.”

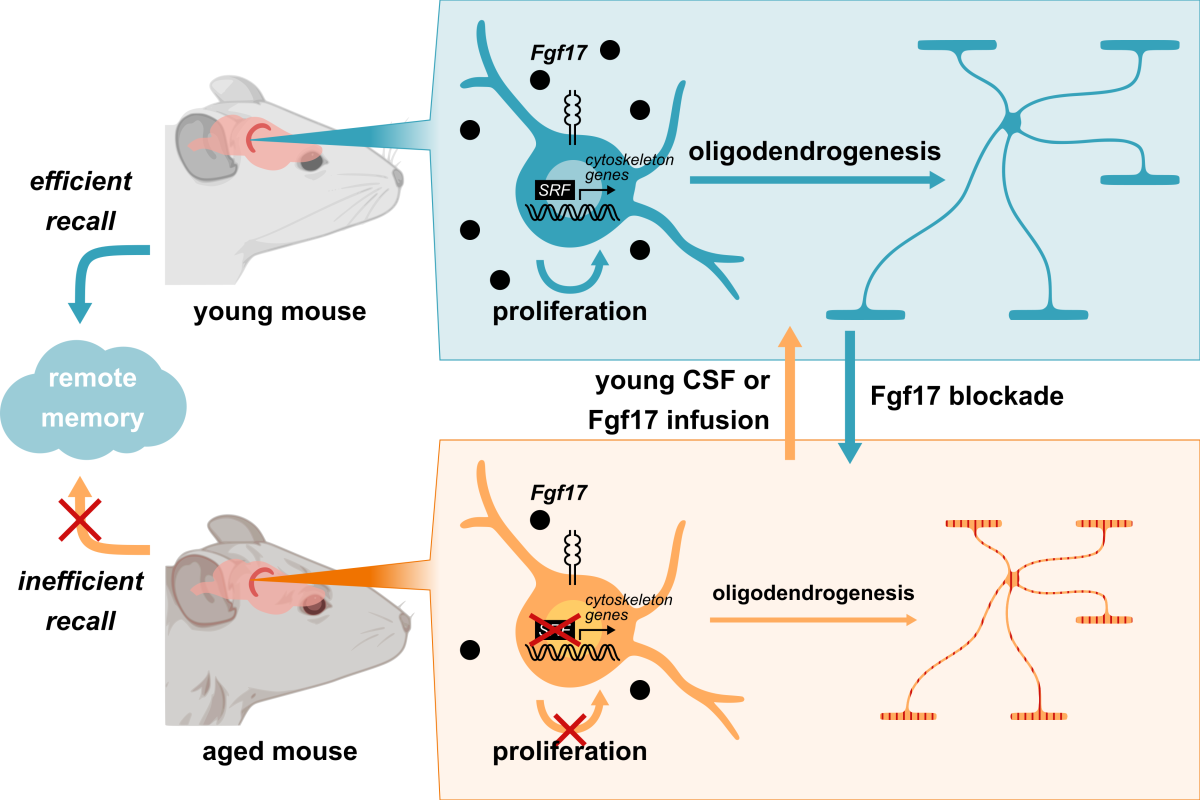

First Iram showed that a week of infusions of CSF from young mice into the brains of old mice could boost the performance of old mice on tests of memory. To find out why, she then employed an RNA sequencing approach that would show her which genes were being expressed more in response to contact with young CSF. Iram was surprised to see that many affected genes were related to oligodendrocytes and myelination. Though oligodendrocytes are known to support communication by insulating—or myelinating—the axons of neuron’s, these cells have long been considered mere support structures and overlooked in many investigations into cognition and aging.

Neither Iram nor Wyss-Coray had ever worked with oligodendrocytes before, but with help from oligodendrocyte experts in the lab of Bradley Zuchero, an assistant professor of neurosurgery, their team began to examine how and why these cells change in the presence of young CSF. Unlike with neurons, the precursors of oligodendrocytes—the cells that have the potential to become them with the right inputs—are still found in high quantities in the adult and aged brain and are theoretically capable of proliferating and maturing to replace their damaged counterparts. But as we age, those precursor cells get sluggish and stop responding as well when they are needed.

But Iram’s CSF injections seemed to wake them up. The team found that CSF from young mice could drive the expansion and maturation of oligodendrocyte precursors in the hippocampus, a part of the brain important for learning and memory. That in turn, drove up levels of myelin in mice who received young CSF compared to mice that received a synthetic version of CSF commonly produced for laboratory experiments.

“We saw these memory improvements and then we saw this more youthful function of oligodendrocytes and their precursors,” said Iram. “This is in line with previous studies showing that the formation of new myelin is necessary for the consolidation of new memories, at least in mice.”

Graphical abstract summarizing the findings of the new Nature study. Image courtesy Tal Iram.

The team then linked the rejuvenation of oligodendrocytes to a protein called Serum Response Factor (SRF), which is thought to play a key role in rearrangements of the cytoskeleton as cells, like oligodendrocytes, mature to take on their ultimate identities. SRF expression drops off in aging, but Iram and her team saw that exposure to young CSF reversed that trend. Iram then isolated a protein called Fgf17 from young CSF that, alone, could lead to the same positive effects of young CSF infusion on oligodendrocytes and memory.

“We’ve already started to narrow down which factors could be responsible for the beneficial effects we see from young CSF” said Wyss-Coray. “That’s a key step to developing potential interventions that could someday see us treating the kinds of cognition and memory loss that so often comes with aging.”

Wyss-Coray credits much of the project’s success to Iram, who proposed the research and took on the tasks of collecting CSF from mice—a difficult and painstaking process—while bringing new RNA sequencing technologies to the lab and facilitating collaborations where outside expertise was needed. The “tenacity and initiative” she showed gives him confidence that this won’t be her last high impact study.

“The work she did on this project shows the potential she has to run her own lab,” Wyss-Coray said. “Tal is fearless. She’s a rockstar.”