Here come the assembloids

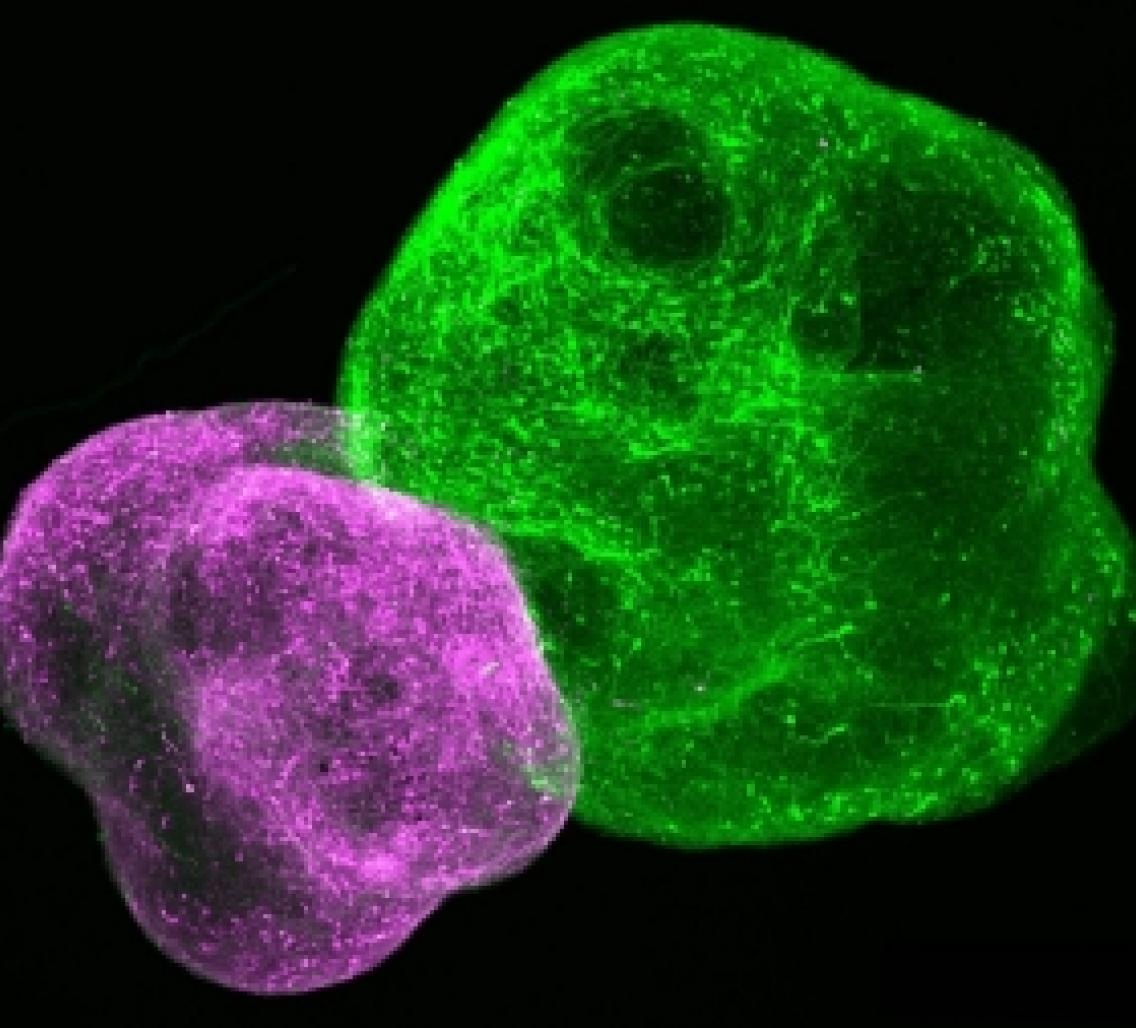

(Photograph by Y. Miura, Sergiu Pasca’s Lab, Stanford University)

By Bruce Goldman

Sergiu Pasca was nervous. Let us count the reasons why.

Because of a pandemic-enforced hiatus, he hadn’t spoken publicly — and indeed, like many of us, had greatly curtailed public contact — for two years.

Now, on the morning of April 12, Pasca, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medicine, was giving a TED talk in Vancouver before an audience of about 1,500. Hectobillionaire Bill Gates had preceded him by a couple of speakers. And he’d been instructed to establish deep eye contact with the strangers in the front row. (That really freaked him out, he said.)

He may have been making the audience a tad nervous too. He was telling them about a discovery guaranteed to raise eyebrows and blood pressure: how to turn anyone’s skin into a replica of a small portion, or portions, of that person’s brain, thriving and growing inside a lab dish.

Pasca, the Bonnie Uytengsu and Family Director of the Stanford Brain Organogenesis Program, assigns a fair share of credit for this feat to the brain. “The human brain largely builds itself,” he said. “It comes with its own assembly instructions.”

Which is fortunate. If, as rumored, the brain really is the most complicated thing in the universe, we’re awful lucky we don’t have to build our own. Of course, if you’re trying to get one to grow in a dish, you are going to have to do some prompting.